by Dr. Gemma Scott

Changing forms of representation are fundamental to our understanding of the history of democracy. The Emergency in India – as well as its visual traces – imposed by Indira Gandhi’s Congress Government from 1975 to 1977, is widely held as one of the most controversial moments in the political history of the subcontinent since Independence. This brief essay analyses specific imagery of the Emergency, a series of published photographs, through which the Congress Party projected an image of popular consent. They highlight how women often dominate this visual narrative, contrasted with an almost complete absence of women from the historiography of the Emergency.[1]

The years prior to the Emergency had witnessed a range of protest movements at the time of a precarious economic situation.[2] The Congress Party lost state elections in Gujarat in early June 1975 to the Janata Front – a coalition of opposition parties backed by leaders such as Morarji Desai, Jayaprakash Narayan (JP), Atal Bihari Vajpayee, L.K. Advani, among others. On 12 June 1975, the Allahabad High Court convicted Gandhi of election corruption, and amidst increasing demands for her to step down from office, Gandhi imposed the Emergency on 26 June. In the months that followed, the state authorities implemented a range of measures aimed at silencing dissent, including the suspension of elections, arresting members of the opposition, censoring the press, and amending the constitution to expand centralised power and restrict the citizens’ fundamental rights.

The government also embarked on and aggressively pursued policies for clearing (demolishing) slums and coercively sterilised parts of the population to meet mandated targets. When Gandhi called for elections in March 1977, they acted as a referendum on Emergency rule. The people voted overwhelmingly against it.

Representing women’s support

Photography was a key component of the Emergency government’s propaganda machine. The party regularly articulated the Emergency’s popularity and published photographs of large crowds at pro-Congress rallies, marches and speeches. Sometimes the party would caption such photographs to explain how the people pictured were offering their support to the Prime Minister. At other times, the party bulletin titled Socialist India, included images of crowds without captions or any explanation of who the people pictured were or what they were doing. Positioned alongside the bulletin’s textual celebrations of the Emergency regime and its achievements, these images were meant to illustrate public support for its measures. Socialist India published many photographs, which can be broadly categorised into two groups. First, photos of prominent individuals in the Party and government, particularly Gandhi herself, reflecting the regime’s increasing personalisation and centralisation of power. Second, the bulletin projected images of popular support for the Emergency and its measures (mostly crowds gathered at rallies and speeches) with women frequently dominating these.

On the other hand, women rarely featured in the Congress’s textual commentary of the imposition of Emergency. For example, in an issue published on 5 July 1975, Socialist India included a photo special titled ‘The People’s Tryst with the Prime Minister’.[3] This evoked Jawaharlal Nehru’s independence speech Tryst with Destiny and showed the Party’s intent to display Gandhi’s popularity with ‘the people’. Women dominate this feature – as many as half of the total of 18 photographs showcase women exclusively. This is entirely disproportionate to women’s presence in the bulletin’s near forty pages of text, which included one report on Gandhi’s message to the International Women’s Year conference held in Mexico City.

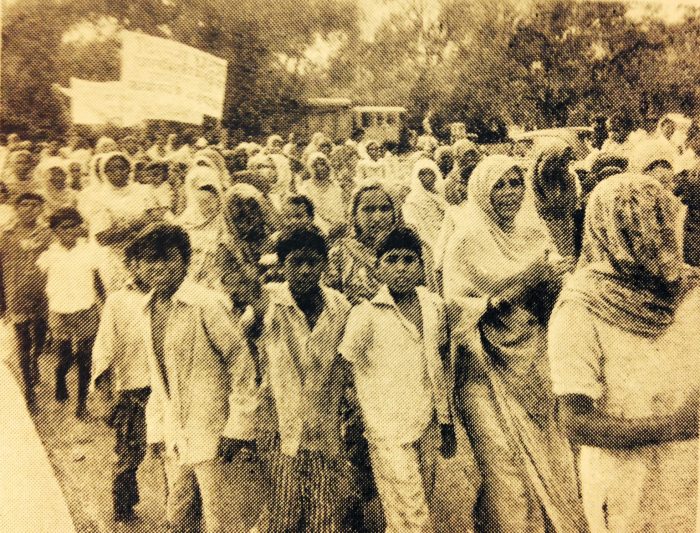

The first page of this special included three close-up images of the Prime Minister and one depiction of popular support, which captured a large crowd of women and children marching with placards. The bulletin captioned this as ‘women and children marching in hundreds to the Prime Minister’s residence on the 14th’ (Figure 1). It was a distinctly gendered projection of mass support – specifically mothers.[4]

The photo depicts a march that took place on 14 June 1975, 12 days prior to Gandhi’s imposition of Emergency. Socialist India regularly used images retrospectively, drawing on images of crowds captured in the pre-Emergency atmosphere, when rallies and public addresses dominated the capital. This edition however focused entirely on the declaration of Emergency and measures imposed under the new regime, and hence women’s presence here implies support. Similarly, the second page of this feature included three photographs of the Party elite and one of an all-female crowd with the caption: ‘a group of women from the hill areas in colourful costumes listening to the Prime Minister’.[5]

The image below (Figure 2), for instance, was captioned: ‘a large contingent of women from the south’, pictured in the grounds of 1 Safdarjung Road, New Delhi, Gandhi’s residence.[6]

Foregrounding the fact that these women travelled from ‘the south’, the bulletin sought to encompass geographical distance, suggesting pan-Indian female support and alluding to women as a category, regardless of location or affiliation. The same page featured an image (Figure 3) of ‘PM with Congress Seva Dal (the Party’s grass roots front organisation) workers’ – all women.

In this photograph, Gandhi stood on an elevated platform, addressing the seated, smiling women, whose eyes are fixed on her. Another image showed a ‘group of elderly women singing kirtan (devotional songs)’. Showing Gandhi facing a group of women holding signs, the final image of this page depicted ‘Muslim women carrying placards which read, “women’s raj” and “down with men”’ as they called on the Prime Minister.[7]

Socialist India invariably gave Gandhi primacy, although the image mentioned above seems to suggest how women’s agendas went beyond her intended mandate. Generally (with the exclusion of that final example depicting the Muslim women’s ‘down with men’ placards) the bulletin did not seek to give voice to the gathered women, their respective causes and agendas. Rather it focused on representing diverse female support groups for Gandhi’s Emergency government from various parts of the country – from multiple faiths, rural and urban locations including college students, elderly women, mothers etc.

Women’s dominant position in visual representations of popular support for the Emergency and its measures continued throughout 1976-1977. On 18 January 1977, Gandhi announced that the elections would be held in March and Socialist India subsequently utilised this strategy for projecting popular support through women-dominated images once again. One page featuring text on Gandhi’s election campaign showed ‘a vast sea of humanity’, a large crowd with barely discernible faces, emphasising scale over cause. The close-up images also showed only women, smiling and raising their arms in the air, actively supporting Gandhi’s campaign through prominent gestures.[8] This stress on female-dominated crowds saturated the issue published on 5 March 1977 (Figure 4).

The image was not captioned, but positioned alongside a report on Gandhi’s various meetings and public addresses, quoting from her election speeches, particularly her reflections on the Emergency: ‘though it was a bitter pill, it had its effect. There was discipline all over the country and economic stability was also achieved’.[9] It superimposed a close-up of Gandhi at a microphone next to a cropped image of the large crowd, resulting in a skewed perspective that visualised only female supporters.

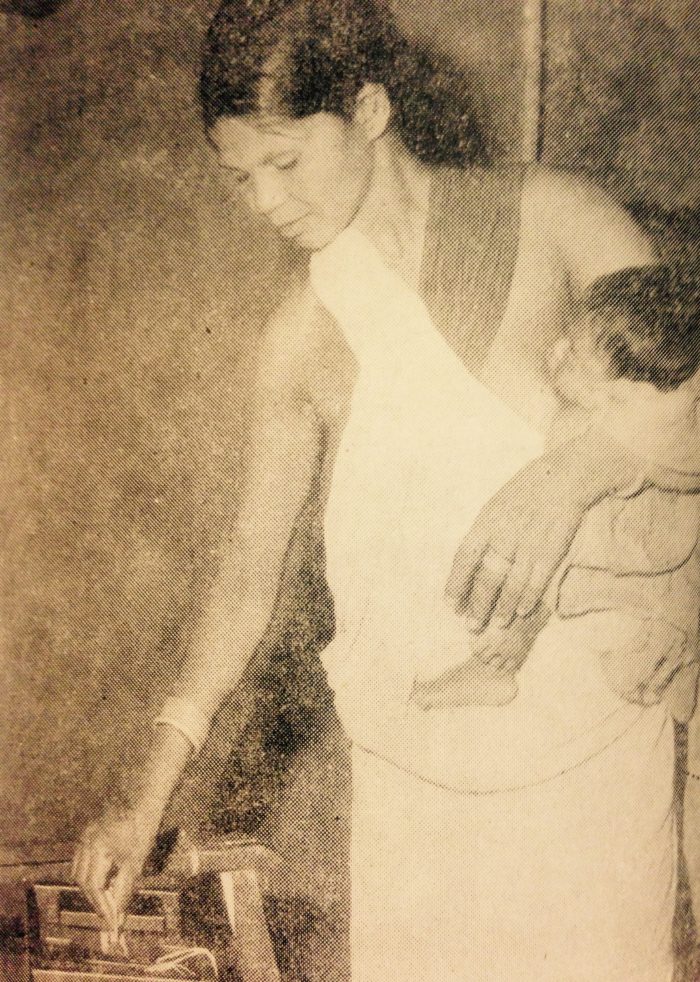

One report, ‘Spotlight on Elections’, featured pictures of men and women voting in a Haryana constituency, including this image the image below, captioned ‘An Adivasi voter’ (Figure 5).[10] The bulletin foregrounds this breastfeeding mother, a focus therefore on women’s gendered roles.

Another showed ‘vote conscious tribal women in colourful attire in a booth in the north eastern region’,[11] while others still depicting close-ups of veiled women casting their ballots (Figure 6) and ‘an official applying indelible ink on the figure of a voter at the Rae Bareli Constituency where the PM, Smt. Indira Gandhi, contested’.[12] Whilst visualising engagement from various groups of women, this emphasis on images of individual and isolated voting contrasted with the few visual depictions of men in this election special. It featured, for example, one image captioned ‘voters on a tractor proceeding to a polling station in Rohtak’ and another showing ‘male voters standing in a queue to cast their votes at a polling booth in Sonepat constituency in Haryana’.[13] Both these images depicted a large mass of male voters – in a long queue, filing into a truck. Interestingly, in this particular feature on the elections, Socialist India represented women almost always in isolation. It did not visualise their collective voting power as it did for men.

Putting women in the picture

Images from Socialist India raise key questions about women’s engagements with the Emergency, and about the regime’s engagements with women. The photographs suggest that women supported Gandhi’s Emergency regime and measures,[14] and show the Congress Party’s pro-Emergency propaganda, while they inversely tell us about the role that images of women and gendered narratives played in this propaganda – Gandhi’s Congress Government actively sought to mobilise women’s support and utilise such backing in their rhetoric – appealing to the nation’s ‘weaker sections’.[15] These photographs therefore highlight a political strategy whereby the Congress government sought to mobilise women in support of Emergency rule, projecting visually striking representations of that support, particularly at key crisis points of the Party during the Emergency.

However, aside from the captions, many of these images stand isolated – their origin, location, and photographers are not referenced. The images give the impression of female mass support for the party and its emergency measures, without articulating what they were actually saying. This begs considerable questions about the role of women in other elements of the history of the Emergency too. For instance, how did women experience programmes such as sterilisation and demolition? In what ways were women involved in resisting the imposition of Emergency rule?[16] As a consequence, perhaps these photographs can then help us move towards a more representative narrative of the history of the Emergency.

References

Guha, Ramachandra. India After Gandhi: The History of the World’s Largest Democracy. London: Macmillan, 2007.

Lockwood, David. The Communist Party of India and the Indian Emergency. London: Sage, 2016.

Maiorano, Diego. Autumn of the Matriarch: Indira Gandhi’s Final Term in Office. London: Hurst & Co., 2015.

Scott, Gemma. ‘”My wife had to get sterilised”: exploring women’s experiences of sterilisation under the Emergency in India, 1975-1977’. Contemporary South Asia, 25.1, 2016.

Scott, Gemma. ‘”Women will have to fight this battle”: political prisoners under India’s Emergency, 1975-1977’. Contemporary South Asia, 26.3, 2018.

Scott, Gemma. Emergency from the Emergency: women in Indira Gandhi’s India, 1975-1977. PhD Thesis. Keele University, 2018.

Scott, Gemma. ‘Putting women in the picture: The role of photography in mobilising support for the Indian Emergency, 1975-1977.’ In Photography in India: From Archives to Contemporary Practice, ed. Aileen Blaney and Chinar Shah. London: Routledge, 2020.

Indian National Congress. Socialist India. New Delhi.

[1]This essay draws on work undertaken for my doctoral thesis, Emergency from the Emergency: Women in Indira Gandhi’s India, 1975-1977 (University of Keele, 2018) which broadly sought to address this gap, by analysing the gendered nature of Emergency politics and the ways in which this regime was experienced, supported, and resisted by women. See also Scott, Gemma. ‘Putting women in the picture: The role of photography in mobilising support for the Indian Emergency, 1975-1977.’ In Photography in India: From Archives to Contemporary Practice, ed. Aileen Blaney and Chinar Shah. London: Routledge, 2020.

[2]Guha, Ramachandra. India After Gandhi: The History of the World’s Largest Democracy. London: Macmillan, 2007, 477-478.

[3]‘The People’s Tryst with the Prime Minister,’ Socialist India (5 July 1975): 18-18d.

[4]Ibid., 18a.

[5]Ibid., 18b.

[6]Ibid., 18c.

[7]Ibid.

[8]Socialist India (12 February 1977) 18c

[9]Socialist India (5 March 1977) 3.

[10]‘Spotlight on Elections,’ Socialist India (26 March 1977) 14.

[11]Ibid., 19.

[12]Ibid., 16-18.

[13]Ibid., 15-16.

[14]My doctoral thesis examines this support in much more detail, looking particularly at the ways in which the Congress Party’s Mahila Congress and the National Federation of Indian Women articulated and offered this support. The NFIW was affiliated to the Communist Party of India, the only major non-Congress political party to support the Emergency for most of its imposition. A detailed account of the CPI’s support for the regime, which it retracted towards the end, is available from David Lockwood, The Communist Party of India and the Indian Emergency. London: Sage, 2016.

[15]For example, Diego Maiorano highlights this tendency to appeal to the ‘weaker sections’ as a key aspect of Gandhi’s political strategy that dominated her career, but claims that she did not attempt to mobilise women specifically. See Autumn of the Matriarch: Indira Gandhi’s Final Term in Office. London: Hurst & Co., 2015, 109.

[16]For more on these particular questions see my articles in Contemporary South Asia: ‘ “My wife had to get sterilised”: exploring women’s experiences of sterilisation under the emergency in India, 1975-1977’ and ‘ “Women will have to fight this battle”: political prisoners under India’s Emergency, 1975-1977’.

Dr. Gemma Scott currently works as International Research Development Officer at Keele University (UK). Her PhD research, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council and undertaken at Keele University, examined the history of India’s State of Emergency (1975-1977), focussing particularly on women’s activism under it and their experiences of its measures. She has held research fellowships at the Library of Congress, Washington DC and Institute of Historical Research, London.