by Jennifer Chowdhry Biswas

In this interview, visual artist Tahia Farhin Haque from Bangladesh addresses how photography can be used as an agent for change by questioning and challenging gender prejudice and perceptions. Haque believes in the power of women who can influence the world through critical discourse and frequently places them at the centre of her projects in an attempt to counter notions of patriarchy. In this post, she shares her thoughts on representation and symbolism in her work, in order to think broadly about narratives and societal norms.

Jennifer Chowdhry Biswas (henceforth JCB): How did your journey as a photographer begin, and what stands out from that moment?

Tahia Farhin Haque (henceforth TFH): I have been fascinated with photographs and their power to tell a story from a very young age. I found myself drawn to art exhibitions in Dhaka city – at the Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy, and as a teenager I was enthralled by the images on the walls that spoke about the photographer’s journey, as one that was able to capture the subject’s emotions or tell a story with a thousand layers or nuances in just one frame.

I started taking photos when I got my first smartphone. At the age of 19 years, my photos were selected for various inter-university exhibitions in Dhaka. I was chosen for the New Vanguard Special Reportage Prize by Document Journal in 2018 which gave me the opportunity to have my first big exhibition at the renowned Aperture Foundation, New York, in the same year that I was pursuing a Diploma in Professional Photography from Counter Foto – a Centre of Visual Arts in Dhaka, and simultaneously graduating in Biochemistry from the North South University, Dhaka.

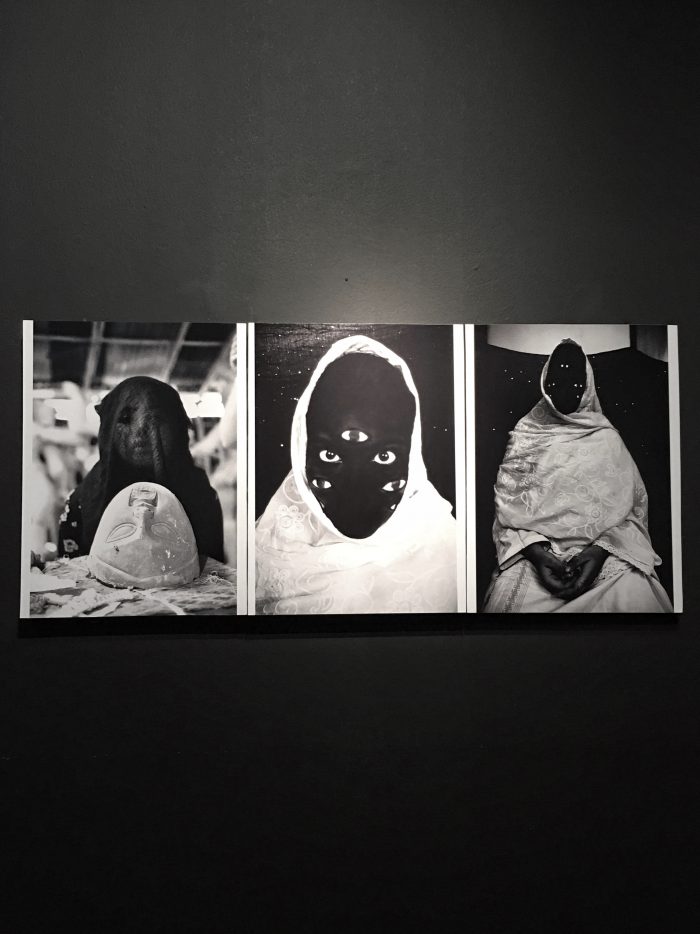

Eventually, I started getting international recognition when my work was exhibited at the London Street Photography Festival, 2018; and the Serendipity Arts Festival, Goa, 2019, which, at a young age was a big honour for me. I am a photographer, yes, but I consider myself an artist, and photography is my medium of expression. I do not want to be confined to just one medium in the future and so I sketch and paint as well. Recently I made artworks with expired lipstick and nail-polish! I also incorporate found objects in my compositions (Figure 1).

JCB: How did you start thinking about a ‘woman’s gaze’ in photography?

TFH: There is certainly a ‘male gaze’ as well as a ‘woman’s gaze’. For me, the woman’s gaze is that part of a story which we usually don’t see, as we often have our stories written by men – which are essentially incomplete. A poem that strongly resonates with me is Jessie Pope’s War Girls originally published in the Daily Mail during the First World War wherein she writes about women taking up work that would have been otherwise done by men – but because men were at war, the women were in control back home. The poet expresses how women were highly capable of working independently. The broader perspective of having an independent voice, to my mind, is part of a woman’s gaze.

During the Liberation War of Bangladesh in 1971, photographers did take photos, but when it came to women, male photographers took photos of raped women, bruised and abused. However, the country’s first female professional photographer, Sayeeda Khanam (1937-2020) who inspired generations of Bangladeshi women and opened doors for female photographers and photojournalists in the country, took photos of women marching, heads held high. Women were not just victims but freedom fighters. It took so many years to respect them as such, and I believe photography as a language has role to play in how we remember the past in general.

When I was growing up, even advertisements in leading newspapers and magazines were highly sexist. We live in a patriarchal society and it’s difficult to undo that, but women’s issues and struggles have to be highlighted and respected for a better society to emerge.

JCB: Who most influenced your work at a personal level?

TFH: My elder sister passed away when we were children. I think I was influenced by her. She left a void in my life. As a specially-abled child she was bedridden most of her life. I feel the world never ever gave her a chance. But through my photography practice I have tried to keep her memory alive.

I come from a big family and that itself is a story in itself, many aspects of which condition my own psychological framework. For example, the series Shadows of a Wooden House exhibited at the Dhaka Art Summit 2020, was a project envisioned from the perspective of my grandmother who had to leave our wooden house in Calcutta (present day Kolkata) during the Partition of India in 1947 and was forced to migrate to Bangladesh. The pain and fear she had to face while migrating with a toddler and an unborn child was very harsh. I correlate that moment, even the gaze upon her with all that is unfolding in present times, where women are still forced to feel insecure and humiliated. The abuse may not be seen on their skin, but the very memory of abuse to me is like the strike of blades on skin when remembered.

JCB: Most of your work is monochrome – shadows, silhouettes and veiled figures. Can you talk about this aesthetic?

TFH: I felt comfortable behind the veil. Society may continue to objectify me but it is my choice to either expose or conceal myself. When you try to associate with the bigger picture around women’s narratives, you can’t actually see the whole truth, it is often concealed. Through my work I try to highlight such experiences of obscurity. In one photograph, I depicted many eyes on my face (Figure 2), because I felt that every woman should return the gaze cast upon them!

There is an eerie beauty in black and white images (Figure 3) – the manner in which light and darkness interact to tell a story. Most of my work during the formative years was in monochrome as it allowed me to convey my own emotions in a more realistic manner perhaps and hence capture the audience’s attention. Colours often come with preconceived connotations and with varied sensibilities in people’s minds, which, I felt, may overwhelm the viewer’s outlook or that they may overlook certain minute details in the photograph. I wanted them to be drawn into my images, to question norms by projecting a stark reality.

In the project, I Could Not Save You, I started taking self-portraits (Figure 4) in times of great emotional upheaval, pain or just reminiscing as we didn’t have any photographs of my elder sister. To be honest, it was more of a coping mechanism to deal with the regret of not able being able to help her. Hence, the initial form was much like a diary that I had been writing before I took these photos. These photographs gave me an outlet to release my guilt and helped me in addressing the depression that came with her passing.

JCB: You have worked with The New York Times and UN on a project which later took the form of a book titled This is 18, offering a glimpse into the realities and aspirations of young women across six continents. While this coming-of-age project is informed by cultural differences, it also attempts to transcend ethnic, religious, and geographical boundaries. Could you tell us more about this initiative?

TFH: To commemorate the International Day of the Girl Child in 2018, The New York Times initiated a project to document the lives of 18-year-old girls around the world through the lens of 22 female photographers who were a year or two older than their subjects. This project became about the portrait of girlhood on the cusp of adulthood, experienced from around the world and across cultures.

I was chosen to represent Bangladesh in this project, for which I photographed Shama Ghosh, an 18-year-old girl who lives in the Hindu neighbourhood of Chandpur. In 2018, she was married but was still going to high school. Marriage at a young age for girls is all too pervasive here, but when I was photographing her, I realised how perceptions and outlooks vary. I realised how across geographies our opportunities vary. She was taking care of her children, of her in-laws while she was studying. Despite this, she was cheerful when she met me and we became friends over the time. She had hopes of becoming a teacher one day. She truly inspired me to believe that when we work with stories on the ground, we must observe and relay perspectives from the points of view of the subject as much as possible. The hopefulness she felt at that age of 18 years in spite of her circumstances became a binding factor for the larger photo-project that spanned many countries.

JCB: In your recent project, Duality in Reality, you symbolically highlight the harsh truths of the pandemic during lockdown, reflecting particularly on domestic violence. Can you talk about the series and it’s stylisation?

TFH: The photo-series Duality in Reality, is the culmination of a project titled Colours of Confinement that was made in self-isolation during the pandemic. It is based on our collective consciousness that has been affected by the deadly virus. Perhaps it highlighted a more lethal, psychological virus that lives within us. It attempts to explore all that is subliminal and locked away in our mind’s recesses, which the pandemic made us face. It asks the question, ‘Have you healed?’

Atrocities against women are blatant, and continued during the pandemic with accounts of rape and domestic violence increasing all over the world. For example, the statistics of domestic violence in Bangladesh as collated by Ain o Salish Kendra (ASK), the Secretariat for the Human Rights Forum in Bangladesh mentions that the cases increased in the country to 554 in 2020 from 423 in 2019. As a consequence, in 2020, there were also anti-rape protests in Bangladesh.

For this project, I chose daily-use objects and colours drawn from household items, of food and spices (Figure 5 & 6) that we normally might consume, in order to showcase what most of us were facing at a mental and emotional level routinely – the cruel, brutal reality of life, the problems of our relationships that nobody was open to discussing. Furthermore, I felt that we were more connected to inanimate objects than to people at that moment as the very people we were living with, became the cause of our trauma. Talking about one’s trauma is, and was taboo, so women and children were trapped in the very house that was meant to be a haven. But women who were facing these traumas of domestic abuse, were still performing household chores in a way to counter, or perhaps just bear with the abnormal and harsh domestic situation.

Tahia Farhin Haque is a visual artist, photographer, and researcher from Bangladesh. Her work has been exhibited at Aperture Gallery, New York (2018), Serendipity Arts Festival (2019), and Dhaka Art Summit (2020). Her photographs have also been featured in several international publications including Forbes, New York Times and Aperture. She has recently received The Prince Claus Seed Award in 2021 and was the finalist of the Samdani Art Award, Bangladesh in 2020. Her work is often driven by contours of time and memory, and focusses on the dynamics of gender in a male-dominated society.