WOMEN | PHOTOGRAPHY IV

Editorial IV

Malavika Karlekar

Contributors to this edition of the newsletter offer insights into a mélange of ideas and praxis – memory and recollection through photographs act as a counterpoint to patriarchy, while image-making with the camera shapes identities and helps artistic practice. Mridu Rai visits the work of three women photographers from Northeast India, and Agastya Thapa reviews a unique public exhibition in Kathmandu curated to raise awareness of feminist history and the women’s movement in Nepal as well as to claim public space for women. If, in Rai and Agastaya’s essays, the photograph per se was the focus, Emilia Terracciano analyses how the medium was used by artist Nasreen Mohamedi (1937-1990) ‘who during her life mobilised the camera as an indispensable image-making apparatus’.

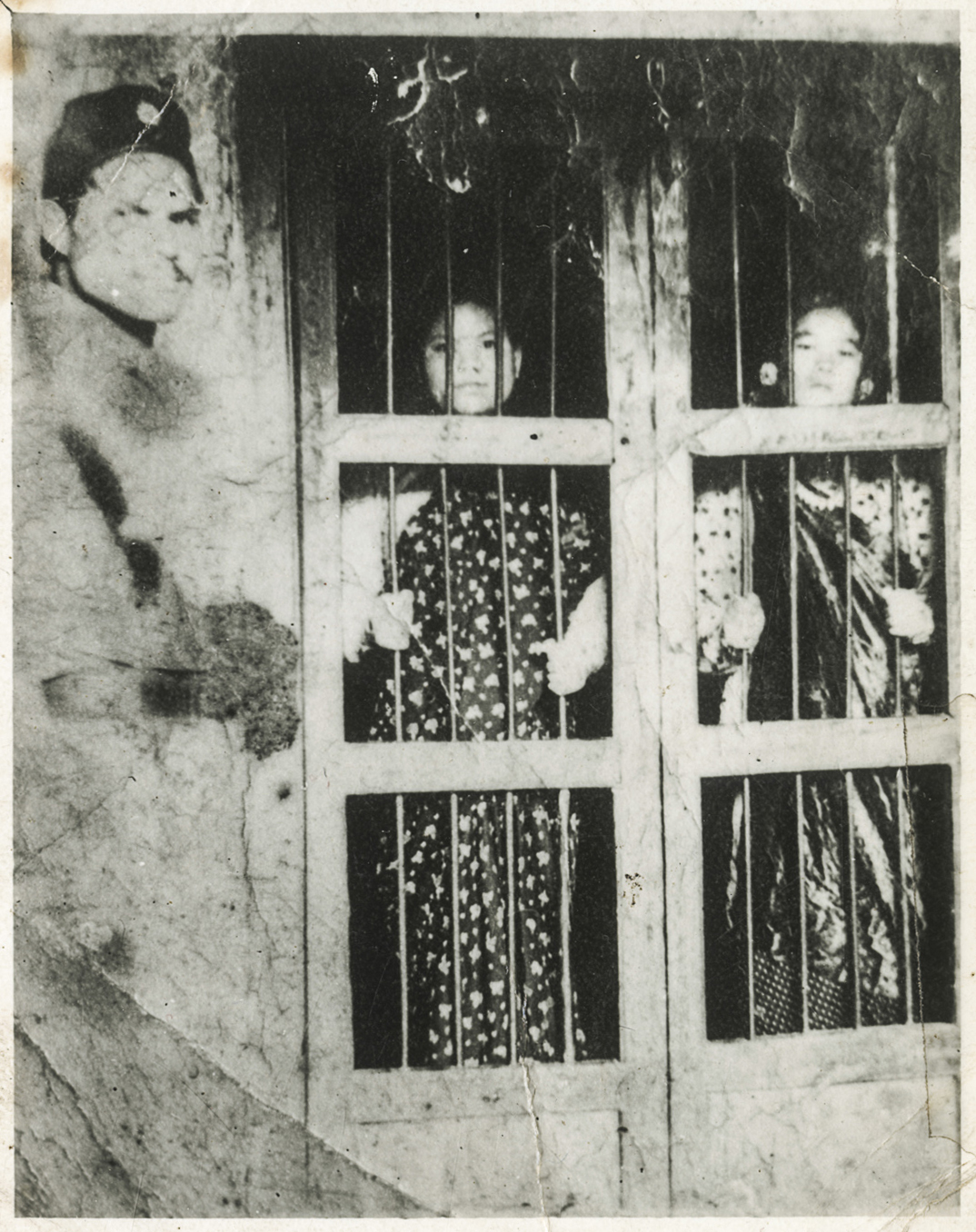

A dog-eared photograph, ‘rare, old, weathered’, taken at the Dillibazar Prison in Kathmandu in 1961, started off the Nepalese women’s journey with memory, reflection and recall. In 2018, using the historical site of Patan Durbar Square in Lalitpur, Kathmandu, the Feminist Memory Project (FMP) held its exhibition The Public Life of Women: A Feminist Memory Project. It was an ‘archival campaign’ undertaken by the Nepal Picture Library (NPL) as part of Photo Kathmandu, a festival dedicated to photographic practices. The festival, that was on for a month, ensured a sustained public exposure to photographs documenting different aspects of Nepalese women’s lives, as well as other memorabilia such as letters, diaries, postcards and even a few household articles. So much so that viewers were heard commenting on the visual overload – a sentiment welcomed by the curatorial team, as one of the aims of the exhibition was ‘to confound and confuse complacent viewers who tend to reflexively trivialise and categorise any cultural activity associated with women as advocating for “women’s rights and women’s empowerment”’.

The photograph as a statement was echoed by Chingrimi Shimray, Menty Jamir and Millo Ankha from Northeast India. In her examination of their work, Mridu Rai found that image-making had a strong presence in the process of identity formation and learning about specific communities. The emergence of public spaces here echoes the experience of the Nepalese women in Kathmandu – as she photographs Popis (female priests), Ankha finds that community spaces that are now open to women allows them to ‘become active in the production and dissemination of culture’. While photographing, both Chingrimi and Menty re-define the portrait. Chingrimi, a visual artist and researcher from Manipur, was involved in documenting textiles of the Tangkhul, a Naga tribe. In the process, she found interesting variations among traditional women: she artfully photographed her aunt’s left arm and shoulder resting against a door jamb. Otherwise an extremely traditional tribal woman, during the isolation of Covid-19 she wore New Balance trainers, a ‘flashy pink raincoat’ to match her nail polish, and fashionable tops. The process of identity formation and self-discovery led Menty to turn the lens ‘inwards, towards herself, her body’. As a self-portrait zooms in on a part of her neck with droplets of water/sweat, she is ‘in control of both the performance and the gaze, rather than being a prop for someone else’s fictive projections’.

Nasreen Mohamedi did not ‘wish to encourage the view that photography bore any overt relationship to her creations’; however, Terracciano feels that the artist’s oeuvre was helped considerably by her photographic practice. Exposed from a young age to the world of cameras and photographic equipment, she used these with ease and comfort. As Mohamedi primarily produced abstract works based on tracing inked lines on paper, the camera was useful in creating ‘simple and frugal geometries’ that characterise her art. A means to an end, the camera was a valuable prosthesis in her world of abstraction, often providing aspects and angles that were not necessarily easily visible in the everyday world. Terracciano uses an evocative analogy to describe Mohamedi’s photography: for her it was an essential practice similar to that of ancient calligraphists who practiced archery so as ‘to develop concentration, insight, and greater mastery of the perceiving mind’.

All three essays in this edition of the Newsletter have, in different ways, underlined the complicity of the photograph, its malleability and obliging nature. Whether in relation to photographers in Northeast India, or motivated participants in Kathmandu’s Feminist Memory Project, or Nasreen Mohamedi’s highly individualistic use of photography as an aid to her art, the camera effectively worked in tandem with – and, in the case of the photographers from Northeast India, became a part of – deeply personal artistic expression.

CONTRIBUTIONS:

UNLEARNING OUR “NORTHEASTERN” BEING: IDENTITY AND IMAGE-MAKING

Mridu Rai

FEMINIST MEMORY PROJECT PHASE I: TELLING LIVES/SHOWING SELVES THROUGH PHOTOGRAPHS

Agastaya Thapa

TILT, SWING, CROP, FOLD! NASREEN MOHAMEDI’S PHOTOGRAPHIC PRACTICE

Emilia Terracciano

Malavika Karlekar is Editor, Indian Journal of Gender Studies and Curator of Re-presenting Indian Women: A Visual Documentary, 1875–1947 and the annual calendar based on archival photographs of women, all at Centre for Women’s Development Studies, New Delhi. Since 2001 she has been researching and writing on archival photographs. Her recent publication Of Colonial Bungalows and Piano Lessons: An Indian Woman’s Memoirs (2019), a volume edited with an Introduction by Karlekar narrates childhood memoirs of her mother, Monica Chanda.

Malavika Karlekar is Editor, Indian Journal of Gender Studies and Curator of Re-presenting Indian Women: A Visual Documentary, 1875–1947 and the annual calendar based on archival photographs of women, all at Centre for Women’s Development Studies, New Delhi. Since 2001 she has been researching and writing on archival photographs. Her recent publication Of Colonial Bungalows and Piano Lessons: An Indian Woman’s Memoirs (2019), a volume edited with an Introduction by Karlekar narrates childhood memoirs of her mother, Monica Chanda.

Copy-editing: Smriti Vohra