Emilia Terracciano

Over the past two decades a greater interaction between photography and visual art practice, including drawing, painting, performance and sculpture, has occurred. Further, the prevalence of the internet and rise of sophisticated computer technologies have prompted fascinating questions in relation to the porous status of photography, moving beyond issues pertaining to its indexical, documentary, forensic and performative status (Sawant 2021).[1] The focus of this essay is the artist Nasreen Mohamedi (1937-1990), who during her life mobilised the camera as an indispensable image-making apparatus.

Scholars, curators and writers have noted that Mohamedi’s practice emerged against the grain of contemporary trends within the post-Independence Indian context. Deeply averse to figuration and narrative content, she produced abstract works by simply tracing inked lines on paper. From the 1970s onwards she composed linear drawings on square sheet paper, using pencil, pen and ink. Lines are fine, taut, of differing lengths and sizes, traced at various angles and pressures – they often involve diagonals, sharp angles and textural accretions. They fill the page like ‘a seismograph on which sand patterns or ripples on the surface of the sea are […] precisely charted’ (Sinha 1997).[2] Mohamedi’s compositions are the result of careful perceptual translations of her surrounding environment. Her later creations, roughly from the early 1980s, include geometric shapes emerging from circles, triangles and diagonal lines positioned mid-air on a white surface.

In this respect, Mohamedi’s work continues to complicate and unsettle categories within Indian art history – and specifically, the more figurative and political forms of modernism so far examined by scholars – that took root at the Faculty of Fine Arts, Maharaja Sayajirao University, Baroda (now Vadodara) from the late 1960s onwards (Kapur 2000; Terracciano 2018; Watson 2009).[3] One of the ongoing challenges that her abstract corpus presents to art historians is that after her premature death, the work found in her studio and apartment was largely undated and untitled. Some explanations for her practice and the chronology of her drawings have been sought in the diaries that were found alongside them. But these offer no indication as to how the artist herself wished to orient or view her work.

More recently, scholars have sought to place her pen-and-ink compositions in closer conversation with her sustained photographic practice (Terracciano 2018). Mohamedi, as is well-recorded, did not exhibit her photographs nor wish to encourage the view that photography bore any overt relationship to her creations (Kapur 2000). Yet it is possible to speculate that photography afforded Mohamedi ample possibilities through which to think through, approach and plot the space of the white page. Her knowledge and familiarity with portable cameras and video equipment was unusual for her time, and from a young age she enjoyed greater exposure than most of her peers in India to the most advanced camera and video camera models.

Around 1913, Mohamedi’s father Ashraf Mohamedi had established Ashraf’s, the first photographic trading company in Bahrain, which dealt in sophisticated Japanese photographic equipment (Fig. 1). As Ashraf’s flourished over the years, it expanded across the Persian Gulf. Mohamedi frequently visited her father, regularly spending time in the Middle East (Bahrain, Kuwait, Turkey, Egypt, Iran). Concentrated observation of these stark landscapes through the lens became an important guiding exercise for Mohamedi in the crafting of her non-figurative vocabulary, as one can witness in her numerous notebook entries and photographs. The peripatetic and cosmopolitan Mohamedi owned several cameras and used them frequently, especially during her sojourns as a student in the UK and France, and later as a tourist in the US and Japan. In India, from the late 1960s she took part in several initiatives involving colleagues drawn to the medium of photography at the Vision Exchange Workshop (VIEW), Bombay and from 1972 onwards at the Faculty of Fine Arts, Maharaja Sayajirao University, Baroda.

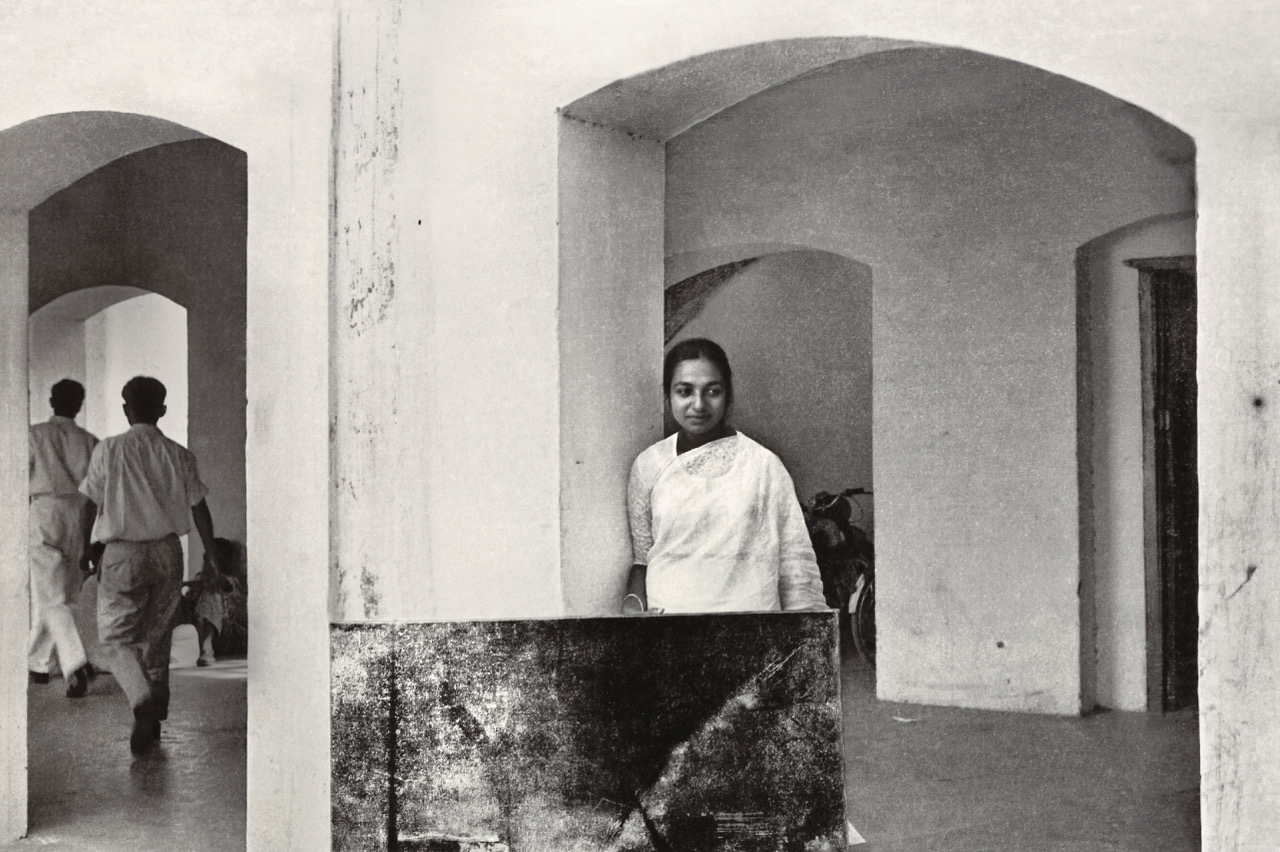

Only a handful of photographs depicting Mohamedi with her works in situ exist today (Fig. 2). These have been used as documents to aid scholars to identify, date and establish a chronology of her oeuvre and, crucially, to identify the actual viewing position of the paintings. Questioning the hegemony of the vertical axis – intended as both a compositional and perceptual principle – Mohamedi further dislocated the normative positionality of the modern ‘vertical man’ (Kapur 2000).[4] Her use of the camera is illustrative in this respect; it both destabilised the positioning of the body in space (Kapur 2000), and aided her to overcome customary ways in which the mind had subordinated vision. As she observes in a 1976 diary entry: ‘The eyes have come at a time when they have been already exploited by the mind.’[5]

Scholars have noted the presence of the syntactical register of utopian abstraction in her corpus, one that emerges from an imagined and elective affinity with revolutionary socialism ‘(especially from the Soviet Union in the 1920s)’ (Kapur 2000).[6] Such investment in defamiliarisation was a crucial and shaping principle of photographic production in the early twentieth century. Defamiliarisation was upheld by Soviet-era photographer Alexander Rodchenko who vigorously propounded the view that photography must respond to the novel realities of industrial and urbanised social life. Rodchenko encouraged the photographer to create images from ‘different vantage points’ (Rodchenko 1913).[7] Further, he elevated the photographer’s propensity for capturing events ‘from inside, from above, down, and from below’, opening up a reality that was truer (i.e., more objective) than the one perceived by the naked eye alone (ibid.).[8] Noting that photographers should monumentalise and celebrate the working lives of ordinary citizenry, Rodchenko recommended that on principle, they should operate their cameras ‘from all viewpoints except from the belly button’; he also declared that the most startling viewpoints were those shot ‘from above down and from below up and their diagonals’ (ibid.).[9]

Mohamedi’s use of the mechanical eye of the camera to select and slice details out of context echoes the Soviet quest to liberate the eye and further cleanse vision, as she radically disengaged the medium from its narrative and representational function. In so doing, she dismantled conventional modes of seeing, peeling away the familiar ways in which custom accreted in the eye, thus proposing new modes of visual perception (Fig. 3).

Exercising tight control over her lens, she used the crop, close-up and unconventional angles to eliminate the middle ground, the very point at which the eye seeks meaning. She mobilised her viewfinder, doing away with figure/ground and vertical/horizontal relationships to set up disorienting overall compositions. Cutting out peripheral vision, she adjusted the lens manually to create startling visual frames, evacuating images of their representational base. Rather than disclosing what is already identifiable, the photographs often reveal some surprising or unfamiliar aspect of the object or event pictured: simple and frugal geometries. Such a desire to deconstruct conventional viewpoints through the application of cropping methods, to create evocative effects with fewer means – literally, less is more – reflects the spirit of Zen, an ethos to which we know Mohamedi was deeply attuned. Altering vision, the camera assisted her in liberating sight from ingrained habits and constraints rooted in every-day perception to release ‘a-historical images’ (Sheikh 2021).[10]

Instead of replicating the human world, Mohamedi’s photography exposes what the painter-photographer and Bauhaus teacher László Moholy-Nagy called the ‘inexhaustible wonder of life’ (Moholy-Nagy [1925] 1967).[11] His influential essay ‘A New Instrument of Vision’ (1936), included in the fine-art curriculum at Baroda, is worth mentioning for its detailed explanation of how sight could be altered by the camera, liberating human beings from the constraints of narrow perception and habitual ways of perceiving reality.[12] The camera is invoked as an extension of human vision: an enhancing prosthesis that could present the world in radically novel ways. Moholy-Nagy spoke of the propensity of photography to render ‘chiaroscuro, shining white, transitions from black to grey imbued with fluid light, the precise magic of the finest texture: in the framework of steel buildings just as much as in the foam of the sea’ (Moholy-Nagy [1925] 1967).[13] He extended this observation to other mechanical media, including gramophones, when he suggested that artists incise grooves on wax plates used for recording in order to generate original, as yet unheard or ungraspable sounds. Similarly, for Mohamedi, the camera could purify vision, offering uncommon sensory and cognitive experiences.

Although it is possible that Mohamedi did take inspiration from Moholy-Nagy’s writings, it is important to note that she did shoot from the belly button, focusing her lens on subjects that Rodchenko would have found short of revolutionary, and probably entirely distasteful. We observe zebra crossings, pavements, toes and feet, the desert and the seashore, and some built environments. What these photographs “do” is to give form to Mohamedi’s need for an uncluttered vision, altering through vertiginous means the position of the viewer in relation to her surroundings. Her photographs, as Atreyee Gupta has pointed out in relation to contemporary developments in photographic abstraction and architecture in India, ‘managed to catapult the human body into abstraction by utilising circular passages in architecture like viewing apertures’ (Gupta 2017).[14] The cities and architectural landmarks Mohamedi selected are typically stripped of their references: a treatment that finds ample resonance in the wordlessness of Zen monastic precepts. Her photographs of Fatehpur Sikri, the Mughal city commissioned by the emperor Akbar in the late sixteenth century, evidence her interest in bare forms: a shady corner, steps, tiles, and water channels. Drawn to the sophisticated architectural features of this city, once surrounded by water,[15] Mohamedi lingers on parallels, zigzags, criss-crosses and multiple points of rest and flight (Fig. 4).

Mohamedi’s treatment of the city of Chandigarh, designed by Le Corbusier, is seemingly devoid of the weight of history (Fig. 5).[16] Built from scratch on desert terrain, Chandigarh was a bold modernist experiment in civic design commissioned by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru in 1950, and constructed by an international team of architects with a view to rehabilitating the state of Punjab following the genocidal violence of Partition.[17] Nehru described Chandigarh as ‘a new town, symbolic of freedom in India, unfettered by the traditions of the past, an expression of the nation’s faith in the future’ (Prakash 2008).[18] But by 1977, when Mohamedi first visited this temple of modern India, Chandigarh produced little affective resonance, and the powerful landmark no longer incarnated the democratic goals of the country’s modern citizenry.[19] Mohamedi pairs the Mughal city of Fatehpur Sikri and this temple in her pursuit of hypnotic space.[20] She writes: ‘There must be space far beyond the logical – to be able to grasp the order within the apparent disorder. I was in Chandigarh where I feel as if Corbusier built areas for the value of defining space. Different but again a hypnotic feeling for space in Fatehpur Sikri. I am by the sea. Such vastness. Nature has its own secrets’ (Mohamedi 1980).[21] Le Corbusier himself referred to his highest architectural intentions as ‘poésie’, probably with Mallarmé in mind (Carl 2003).[22] We know that the architect conveyed this phenomenon in terms of the extremes of representational possibilities: of setting in space, and of language. He coined the expression espace indicible (‘a space beyond words’) to describe this ideal experience of formal emptiness in both spatial and linguistic terms.

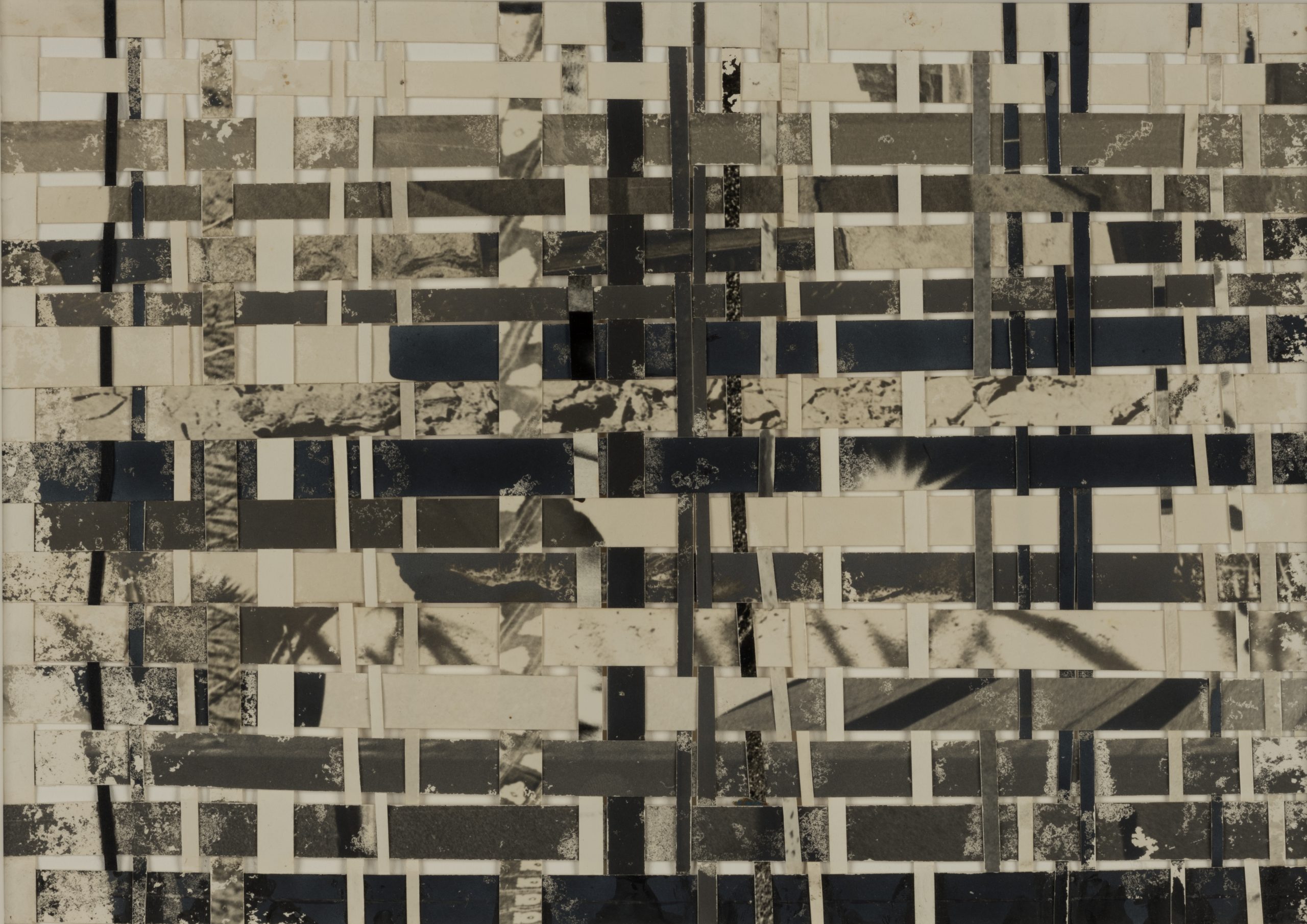

The camera was a mobile eye that allowed Mohamedi to achieve greater focus. Waiting, and ‘gathering attention’ (Kapur 2002),[23] she used this apparatus to single out everyday ‘targets’, in the same way that ancient calligraphic masters pursued archery as daily practice to develop concentration, insight, and greater mastery of the perceiving mind (Terracciano 2018).[24] Moreover, the camera reinforced her control over reality, distilling perception from extraneous and contingent inner and outer noise. As such, her photographs were in all probability mnemonic records meant to help her document and resolve the problems that she posed to herself while plotting her compositions, through cursive jottings she made in her diary, detailing formal concerns or poetic insights. Ultimately, the practice of crafting her hand-drawn lines in ink granted her an openness that the medium of photography closed off. Yet, even while Mohamedi used the camera as a ‘warp’ (in the sense of Old English weorpan, ‘that which is thrown away’), it undergirded her practice, continuing to serve her as a crucial technology with which to fabricate, mobilise and tease out new visual entry points into and beyond the everyday (Fig. 6).

Notes

1. Shukla Sawant, ‘Photo-Fact, Photo-Fiction: Constructing Artist Photography in Modern and Contemporary Indian Art’ in Partha Mitter, Parul Dave Mukherji and Rakhee Balaram, 20th Century Indian Art: Modern, Post-Independence, Contemporary (London: Thames and Hudson, 2022), p. 444.

2. Ajay Sinha, ‘Envisioning the Seventies and the Eighties’ in Contemporary Art in Baroda, ed. Gulam Mohammed Sheikh (New Delhi: Tulika, 1997), p. 171.

3. See, for example, Emilia Terracciano, ‘Fugitive Lines: Nasreen Mohamedi 1960-1975’, Art Journal, Vol. 73, No. 1 (2014), pp. 44-59; Geeta Kapur, ‘Again A Difficult Task Begins’ in Nasreen Mohamedi: Waiting Is a Part of Intense Living’, exhibition catalogue (Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, 2016); Robin Simpson, ‘Life Injected with Life: Locating Tolerance in Nasreen Mohamedi’s Abstraction’ in Sarai Reader 09: Projections (Delhi: Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, 2013), pp. 2-9; Suman Gopinath and Grant Watson, Nasreen Mohamedi: Notes – Reflections on Indian Modernism (Part 1), exhibition catalogue (Oslo: Centre for Contemporary Art, 2019); Suman Gopinath and Grant Watson, Drawing Space: Contemporary Indian Drawing, exhibition catalogue (London: Institute of International Visual Arts, 2000); and Grant Watson, ‘Passage and Placement: Nasreen Mohamedi’, Afterall Journal, No. 21 (2009), pp. 28-35.

4. Geeta Kapur, When Was Modernism: Essays on Contemporary Cultural Practice in India (New Delhi: Tulika, 2000), p. 323.

5. Nasreen Mohamedi, diary entry (16 April 1976, Baroda) in Nasreen in Retrospect, ed. Altaf (Bombay: Ashraf Mohamedi Trust, 1995), p. 97.

6. Geeta Kapur, When Was Modernism, op. cit., p. 323.

7.. Alexander Rodchenko, ‘The Paths of Modern Photography’ in Photography in the Modern Era: European Documents and Critical Writings, 1913-1940, ed. Christopher Phillips/trans. John E. Bowlt, (Metropolitan Museum of Art: New York, 1989), pp. 256-63, at p. 257.

8. ibid., p. 259.

9. ibid., p. 262.

10.Gulam Mohammed Sheikh, in ‘The Gulammohammed Sheikh Interview: Portrait of an Artist’, The Punch Magazine, 25 October 2021; https://thepunchmagazine.com/arts/art-design/the-gulammohammed-sheikh-interview-portrait-of-an-artist. Accessed 14 April 2022.

11. László Moholy-Nagy (1925), ‘The Future of the Photographic Process’ in Painting, Photography, Film, trans. J. Seligman (London: Lund Humphries, 1967), p. 33.

12. Weimar Bauhaus pedagogical methodologies and curricula introduced important notions of design and visual art practice at the university. See Nilima Sheikh, ‘A Post-Independence Initiative in Art’ in Contemporary Art in Baroda, ed. Gulammohammed Sheikh (New Delhi: Tulika, 1997), pp. 55, 267 (note 6).

13. László Moholy-Nagy (1925), op. cit.

14. Atreyee Gupta, ‘Dwelling in Abstraction: Post-Partition Segues into Post-War Art’, Third Text 31, No. 2-3 (2017), pp. 433-57.

15. The Hindi word saik means a ‘place surrounded by water’. Located on upper red sandstone ridges of the Vindhya mountain range, Sikri once had abundant water in a natural lake. The city began to dry up and was finally abandoned in 1585.

16. See Peter Serenyi, ‘Timeless but of Its Time: Le Corbusier’s Architecture in India’, Perspecta 20 (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1983), pp. 110-13; William Curtis, Modern Architecture since 1900 (Oxford: Phaidon Press, 1987), p. 277.

17. Vikramaditya Prakash, Chandigarh’s Le Corbusier: The Struggle for Modernity in Postcolonial India (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002), p. 7.

18. Jawaharlal Nehru quoted in Vikramaditya Prakash, ibid. The Government of Punjab took the historic decision to create its own capital after losing the Mughal city of Lahore to the newly established neighbouring state of Pakistan through the genocidal partitioning of the subcontinent. By then the main stream of refugees had crossed over to more “stable” states and ancient family and neighbourly ties had been severed.

19. Sunil Khilnani, The Idea of India (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1997), p. 64.

20. Despite Le Corbusier’s imperative to erase historical traces of the past through the example of Chandigarh, historians have variously noted that his use of large reflective pools of water, devised to demarcate governmental zones from ordinary civic quarters, may well have drawn from historical Mughal architectural examples. Scholars cite the examples of the portico of the Assembly (Parliament) and the front of the High Court at Chandigarh which formally echo the seventeenth-century Diwan-i-Am in the Red Fort in Delhi.

21. Mohamedi in a letter to Anna Singh, 20 May 1980 [my emphasis]. For an interesting account of Le Corbusier’s Chandigarh as ‘mirage’ and ‘optical phenomenon’, see Atreyee Gupta, ‘In a Postcolonial Diction: Postwar Abstraction and the Aesthetics of Modernization’, Art Journal, Vol. 72, No. 3 (2013), pp. 30-46.

22. Peter Carl, ‘The Tower of Shadows’ in Tim Benton et al, Le Corbusier and the Architecture of Reinvention (London: Architectural Association, 2003), p. 100.

23. Geeta Kapur, ‘Elegy for an Unclaimed Beloved: Nasreen Mohamedi 1937–1990’, Tate Research Publication, 2014, https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-liverpool/nasreen-mohamedi/elegy-for-unclaimed-beloved, accessed 10 August 2022.

24. Emilia Terracciano, Art and Emergency: Modernism in Twentieth-Century India (London: IB Tauris, 2018).

Emilia Terracciano is a writer and a lecturer in the history of art at the University of Manchester. Her research interests lie in modern and contemporary art with a focus on South Asia. She collaborates with artists, curators and gallerists in the UK, India and Pakistan, and is a contributor to the art press. She has written essays for Met Breuer, New York; the Pakistan Pavilion at the 58th International Art Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia; Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology Oxford, Glenbarra Art Museum, Himeji; and Light Work, Syracuse.