WOMEN | PHOTOGRAPHY III

Courtesy of Goa Familia Digital Archive

Editorial

Malavika Karlekar

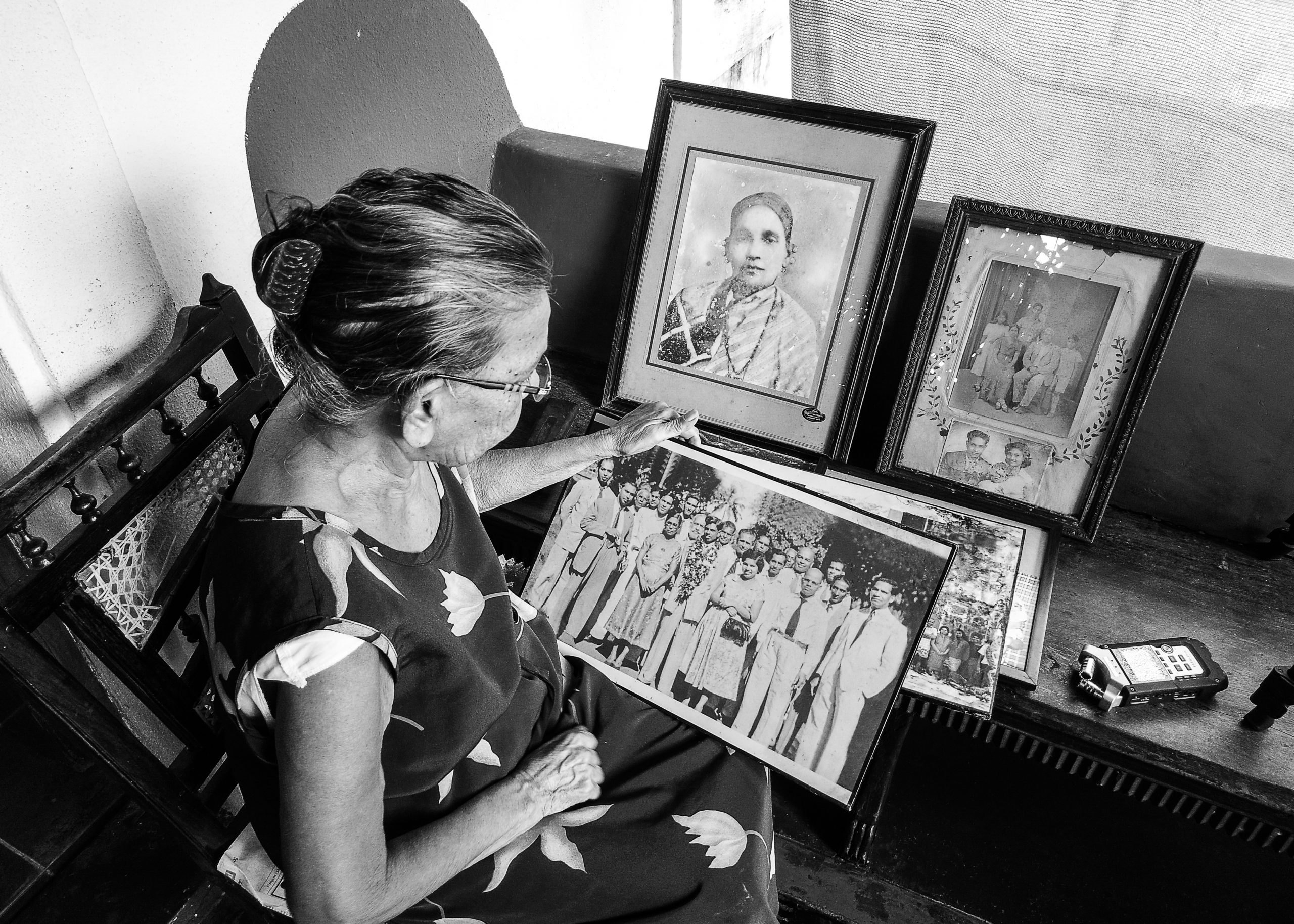

This edition of the newsletter showcases both the personal and the political, melding private imaginings with courageous public visual statements. The three essays also underline the importance of the photographic archive, whether contemporary or historical, institutionalised formally or, as we see, through private albums. For instance, Lina Vincent’s Lives and Memories: Ada | Meera | Antonetta takes us on a fascinating journey of individual women through their albums, “unlocking”, as she writes, “the floodgates of memories and emotions that are usually stowed away in the recesses of the mind”. It is the story of three Goan women – Ada Ribeiro, Meera Kamat, and Antonetta Fernandes. A part of the Goa Familia project, their stories go beyond their own lives to frame the wider exploration of community narratives. The photograph becomes a handy tool to record both the moment as well as significant events that crossed boundaries of the everyday. The open album became a talking point, dredging memories of days long past. While working on the Goa Familia project, Vincent “found that a single family member becomes the holder of the archive across generations – the ‘memory keeper’, and takes on the task to care for it”. Though she doesn’t dwell too much on it, for every well-preserved archive, there would be several that found their way to waste paper baskets: valuing a dog-eared sepia-tinted photograph is yet to grow deep roots in India.

Vincent chooses unusual images – that of Ada Menezes dressed for a Bharatanatyam recital, quite unlike “the stereotypical image of what a Goan girl should look like”. In some sense, the photograph symbolised the cosmopolitan background of the Menezes family. On Goa Liberation Day (19 December 1961), Meera Kamat was the only woman to deliver a speech to the crowd in Sanvordem. A grandmother now, leafing through her family album helps Meera recall that though she spoke in Hindi, “my only language was the language of a liberated Goan”. The album as a mnemonic device helped nonagenarian Antonetta Fernandes recount to the researchers, events from her life that was lived in three continents. And her love for the Goan Tiatr, a popular form of musical theatre. Vincent concludes by pointing out that while these three women have never met, “they occupy common spaces in collective memory”, each having seen Goa metamorphose from a Portuguese colony into a part of Independent India.

If the three women from Goa were used to public life from an early age, in Returning the Gaze: The Photography of Sayeeda Khanum, Jannatul Mawa focusses on a different world – Sayeeda Khanum’s frames captured the lives of those with little access to the outside world. Even after the Partition of British India, Sayeeda was the only woman photographer in East Pakistan and then Independent Bangladesh, her earliest photographs taken with a box camera. At the age of nineteen, she started her professional career as a photojournalist for the celebrated Begum magazine; years later, she was one of only two photographers permitted to document the on-site shootings and take stills of three of Ray’s films. Sayeeda did not photograph much during the Bangladesh Liberation War; nor did she want to portray women as victims, naked and abused, but rather she photographed them as they proudly carried guns – a counter-narrative to subjugation and victimhood.

However, the trope of victimhood resurfaces in Anshika’s photo-essay Erasure as Evidence that focusses on Nida Mehboob’s work among the persecuted Ahmadi Muslims of Pakistan. The author uses the term ‘performative photography’ to explain Mehboob’s work. The photograph, explains Mehboob, is a means to “. . . document that which has not been told yet”. Thus, in A Survival Guide for Ahmadi Muslims of Pakistan (2021) “photographs are accompanied by graphic text” which critically foregrounds “how the Ahmadis can feel safe [only] by being invisible in the country”. Her images bring to life years of discriminatory politics and religious persecution of this minority. A woman’s distinctive style of wearing the burqa is a signifier, a symbol encouraging public harassment and abuse. How then, do women claim their own identities if their very existence is threatened?

Mehboob’s brave images equally communicate the uncertainty of human life – just as the revelations of Goan family albums reaffirm a joie de vivre, a celebration of continuity and change. And Sayeeda Khanum bridges this chasm, her long photographic career recording the delicate tapestry of the quotidian as well as the dark undersides that characterised the birth of a nation.

CONTRIBUTIONS:

RETURNING THE GAZE: THE PHOTOGRAPHY OF SAYEEDA KHANUM

Jannatul Mawa

ERASURE AS EVIDENCE

Anshika Varma

LIVES AND MEMORIES: ADA | MEERA | ANTONETTA

Lina Vincent

Malavika Karlekar is Editor, Indian Journal of Gender Studies and Curator of Re-presenting Indian Women: A Visual Documentary, 1875–1947 and the annual calendar based on archival photographs of women, all at Centre for Women’s Development Studies, New Delhi. Since 2001 she has been researching and writing on archival photographs. Her recent publication Of Colonial Bungalows and Piano Lessons: An Indian Woman’s Memoirs (2019), a volume edited with an Introduction by Karlekar narrates childhood memoirs of her mother, Monica Chanda.

Malavika Karlekar is Editor, Indian Journal of Gender Studies and Curator of Re-presenting Indian Women: A Visual Documentary, 1875–1947 and the annual calendar based on archival photographs of women, all at Centre for Women’s Development Studies, New Delhi. Since 2001 she has been researching and writing on archival photographs. Her recent publication Of Colonial Bungalows and Piano Lessons: An Indian Woman’s Memoirs (2019), a volume edited with an Introduction by Karlekar narrates childhood memoirs of her mother, Monica Chanda.