by Anshika Varma

The photograph awakens a desire to know that which it cannot show, for it is perhaps an ultimate unknowability which is at the center of the photographs historical challenge. We are faced with the limits of our own understanding in the face of the ‘endless’ to which photographs refer. – Elizabeth Edwards[1]

In considering the photograph as a form of resistance, the indexing of visual frames of activism across the subcontinental region often provokes and questions the evidentiary nature of photography itself. This relationship, between subject and image-maker is intricately investigated while photographing the ‘familiar’ and documenting the contours of belonging as an exercise in exploring intimacy. What if, however, the context in which the images are made threaten to erase one’s very existence?

Nida Mehboob’s ongoing work, Shadow Lives (2017-), attempts to illuminate this delicate space between the worlds of the ‘performative’ and the ‘documentary’.

Mehboob’s images look upon years of discriminatory politics as well as the religious persecution of the Ahmadi Muslims of Pakistan. In photographing a known community, and capturing their ways of life, she was brought face to face with a harsh, inevitable truth – their unjust treatment as minorities. Her images, at first, may appear as straightforward identity imagery of a persecuted community, but they go further in voicing social concerns and political predicaments in the present. Staging moments from the everyday, created through recorded testimonies and observations, each image becomes both – the painful recollection of an incident and rampant forms of mobilised instigation and intolerance. Through these assertions, Mehboob questions state power that all too often sidesteps the legitimate claims of those marginalised and dictates the norms of individual expression, especially with respect to a specific faith. The process of reclaiming self-identity, and deconstructing how it is being forcibly manoeuvred and eroded by external powers, become motivating factors for Mehboob’s composition/s – that are not only limited to this series but her broader approach to photography. This includes how Mehboob visualises the dynamics of caste and gender disparity by underlining the constrained autonomy of self-definition in present-day Pakistan, if not the South Asian region as a whole.

As a chronicler of this moment and an image-maker with her own creative practice, she faced several challenges while working on this project, especially when visiting families from the community who did not believe that change was possible. It was, she asserts, because she was a woman. Mehboob was acutely aware that these constraints were rooted in age-old gender biases that now became almost casually accepted. She feels that this entrenched bias extends to her own profession that is dominated by male practitioners.

“One could easily see how deep the patriarchal system was . . . because men had the desire to dictate whose stories would be allowed to be told, and to whom”, she says while discussing issues of access while working on the project. Mehboob then turned to women, urging them to share their stories in private, safe spaces. And this very process of opening up a dialogue became the underlying means for creating the images.

I discussed the systems and strategies that Mehboob deployed in order to evolve her distinct visual language. Mehboob’s words stayed with me, “We used whispers as a tool of our resistance. We created the work from a sense of a shared experience”. Each image emerged from prolonged deliberations about how visual narratives could be used to communicate beyond the literal, to explore photography’s ability to ‘symobolise’. For instance, though the burqa in the social consciousness has become a stereotype associated with Islamic extremism, in this project, attention was paid to it as an everyday attire, worn in a distinct way by Ahmadi women; and so every person photographed conveyed their story while being partially concealed.

2.2%[2] of the Ahmadi community resides in Pakistan, the largest density in the world. As a consequence, the very site of the project brought to light certain ideological and historical differences between varied Islamic schools and sects, in this case, the Ahmadis and the Sunnis, a majority Muslim community who, like the principal branches of Islam – Sunnis and Shias – have contrasting notions on the successors of the prophet. The Sunni tradition of Islam, places its founder, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, as the promised Messiah. However, this claim was rejected by the dominant community for whom Muhammad was the last of the Prophets and any saint subsequently was considered a mujadid (reformer). Differences between these two schools has deemed the Ahmadis as heretics for some, causing mass violence and destruction.

It is interesting to observe that the religious text which clarifies this division as well as the artist’s response to the ground reality – are both illustrated in the pages of her photobook. Through her own juxtapositions, we see how multiple forms of social ostracisation and an envisioned political freedom can claim and redirect one’s religious identity.

In her recently published book titled A Survival Guide for Ahmadi Muslims of Pakistan (2021), Mehboob is acutely aware of the oriental, colonial and even at times, the contemporary gaze which responds to issues in the global south by superficially sympathising or surmising regional discords to amass social capital. She therefore made a conscious choice to generate a narrative style that would disrupt an overtly benign response. Her incentive was to provoke a public response, by angry even, rather than for viewers to easily concede to her plea.

The images cannot be read bereft of context, especially as the work is insinuatory and signposts larger issues. Mehboob’s work is adaptive and dynamic in its approach, but at its core questions the arc of legal identity issues surrounding the Ahmadis as an Islamic community. Mehboob’s expanded use of the archive and of data surrounding inter-communal unrest itself, at times, becomes the visual medium and message in her work. “I feel a bit out of control. It is only in retrospect, after working as a photographer for almost eight years, that I now realise the maksad (purpose) of photography: to document that which has not been told yet. And I begin to question whether I need to make new images instead of [sharing] this rich archive I already have, my raw material”.

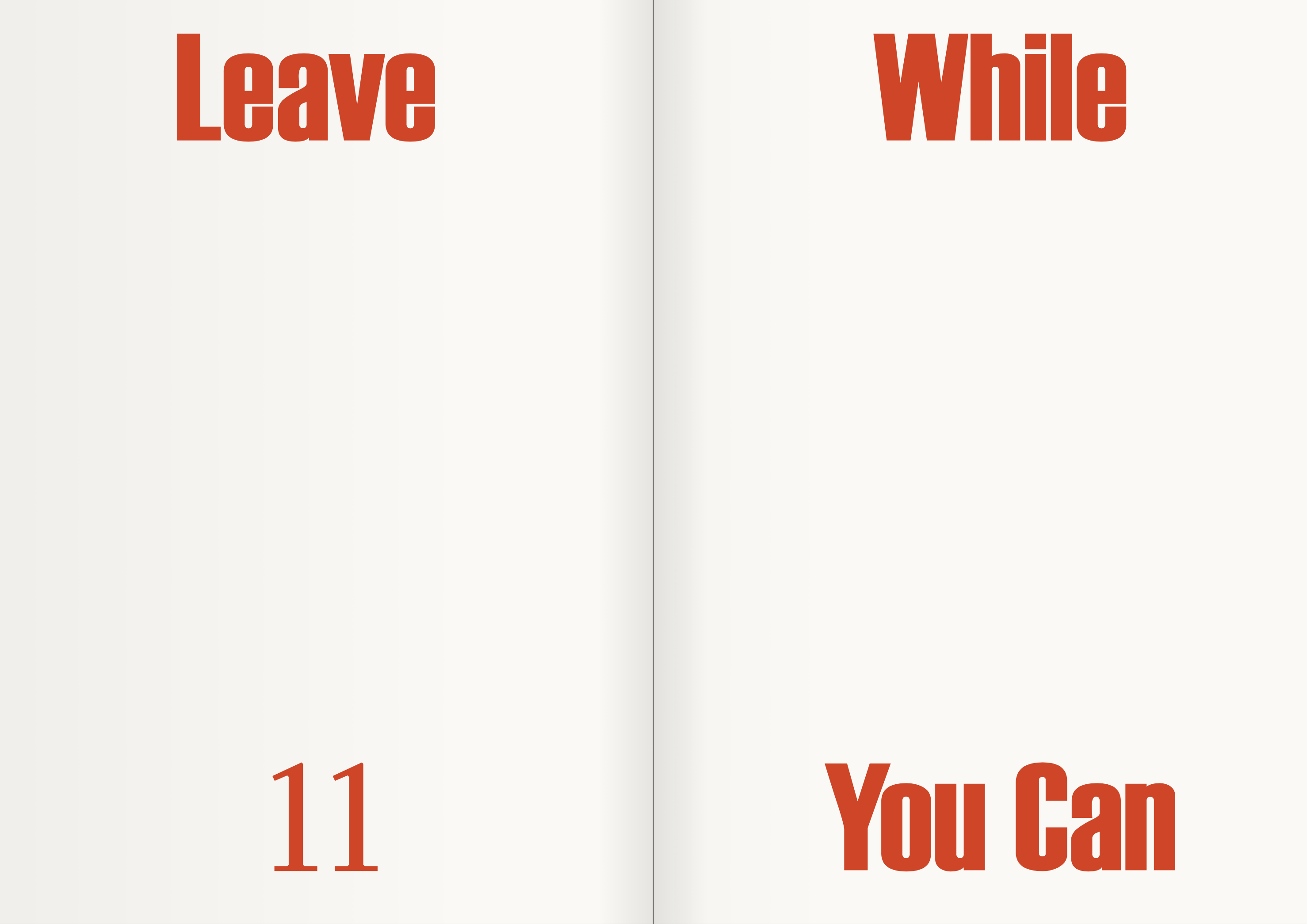

In A Survival Guide for Ahmadi Muslims of Pakistan, her photographs are accompanied by graphic text, ironic and suggestive – they cynically propound how the Ahmadis can feel safe by being invisible in the country. Playing with various colloquial phrases found in advertisement banners across the country such as ‘Get Indoors While Mullah Roars’[3], the text on the pages are presented as unsettling broadcasts, indicative of our insensitive times.

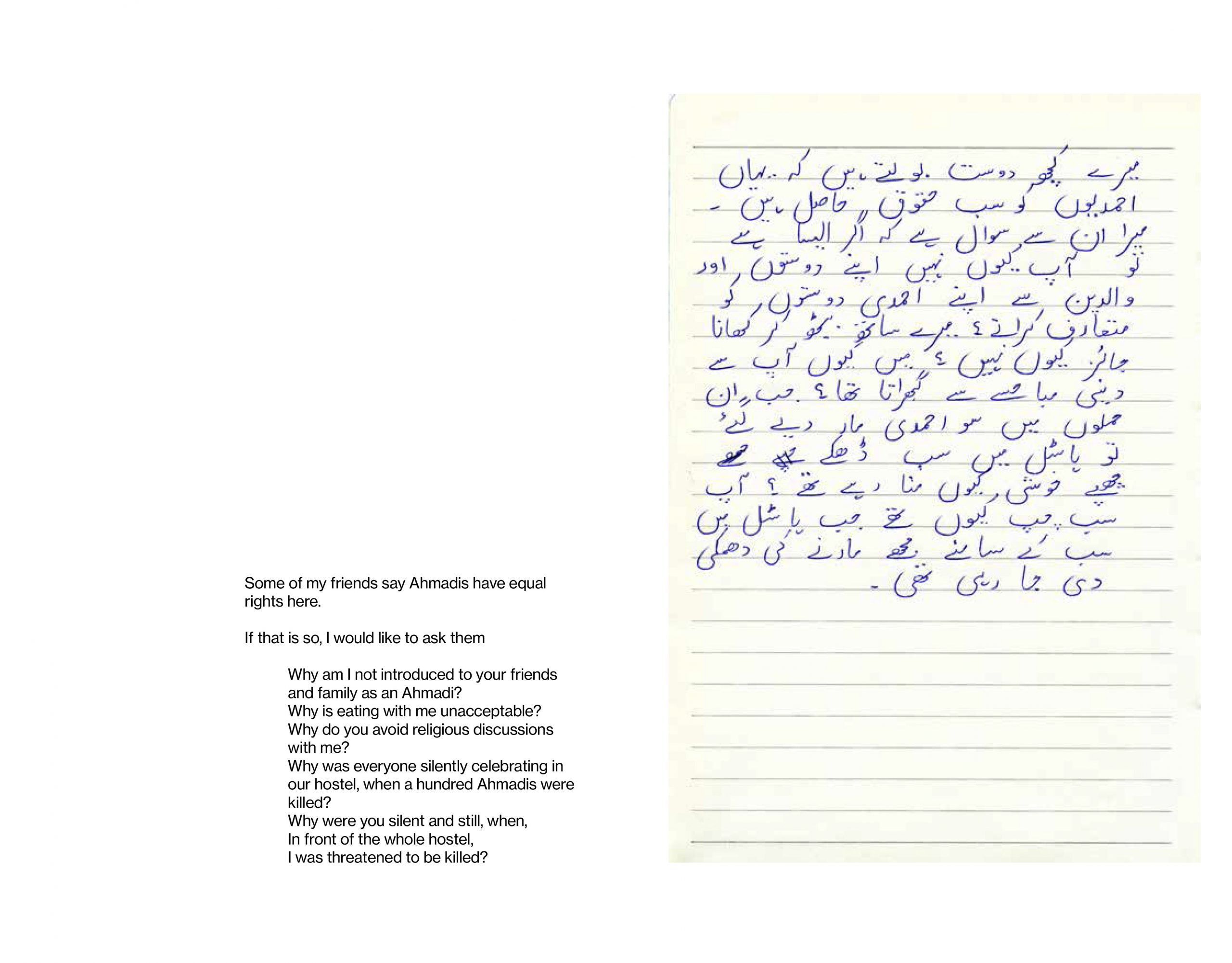

Stark words in red ink are placed together to offer a dry-humoured commentary, insinuating uncanny coping mechanisms for survival that may be adopted by the Ahmadis, such as in the phrase ‘Leave While You Can’.[4] Mehboob perhaps suggests that in their invisibility, lies the path to existence. The tongue-in-cheek language of these headlines is placed alongside testimonials of people from the community who share their experiences of bigotry and violence.

We saw a car full of mullahs arrive. They gathered people around and informed them about the decree that had been issued to kill us because they had found out that we were Ahmadis. All this while we stood far-off, hiding and listening. We were scared for ourselves, our kids, our families. That evening a mob came to our house. We were lucky to stay alive and left the city forever. Many people don’t. – Ali, Quetta[5]

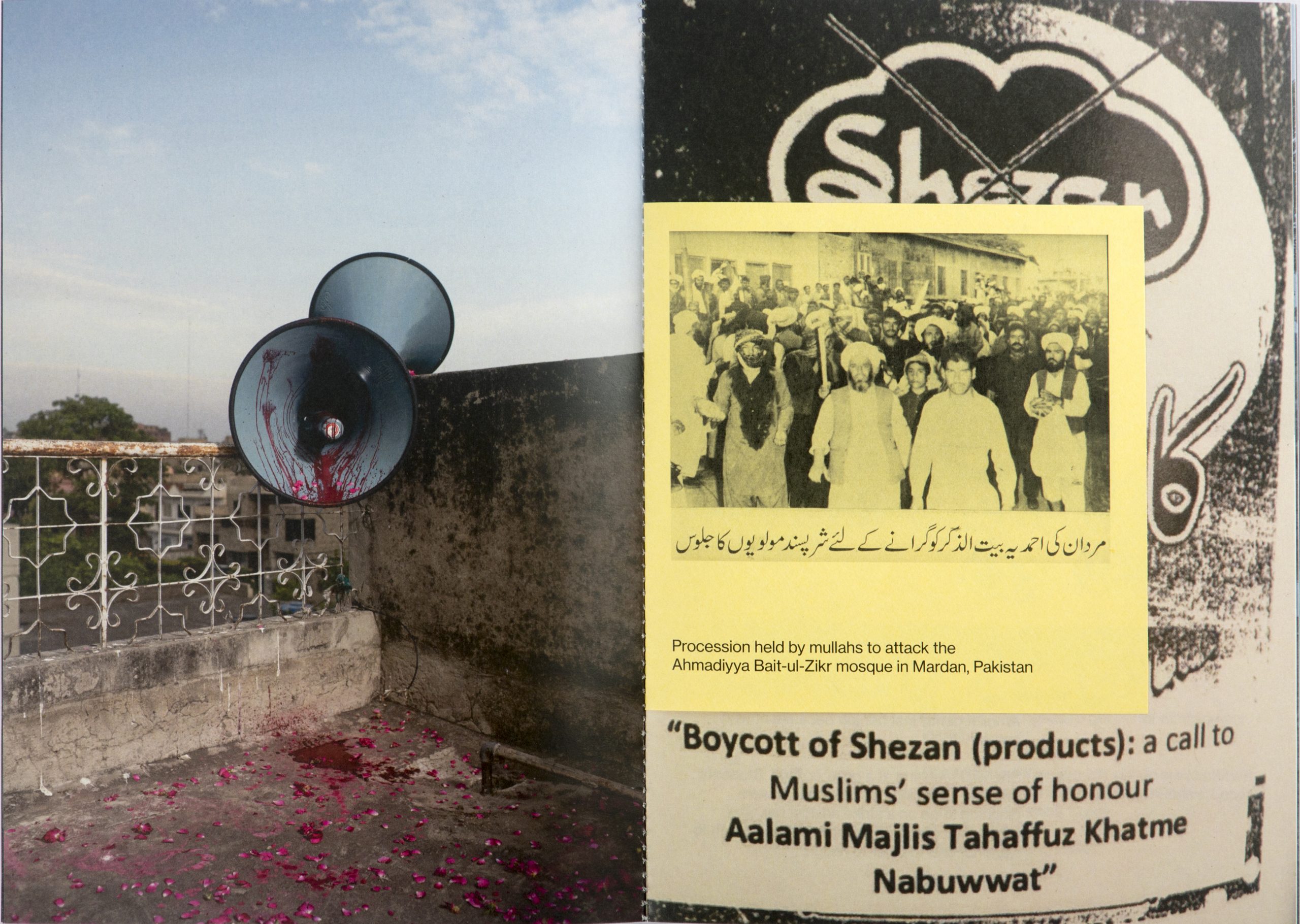

A spread from Guftgu Zine Box – Ahmadi’s of Pakistan (New Delhi: Offset Projects, 2020)

For the artist there was an urgency to create the work, emerging from collective experiences in the country. These are not individual instances fragmented over decades. Conscious acts of aggression have been escalating over time. Take for instance the anti-Ahmadiyya riots in 1974 to 1984, that was a response to the creation of an ordinance in the Constitution of Pakistan restricting the freedom of religion for Ahmadis, under the late President Zia-ul-Haq. The amendment criminalised the Ahmadis’ identification as Muslim altogether, punishable by three years imprisonment.[6]

While curating and designing a different iteration of this work for Guftgu by Offset Projects, Mehboob’s shared further material with me – news clippings taken from B.A. Rafiq’s book, From the World Press (pub. London Mosque, 1975), personal archives of the photographer and hand-written notes during interviews with the community.

The process of curating this work brought to the fore extant social and religious constructs and ways of tackling them within a legal framework. For the first edition of the book, we, as Guftgu, made a collective decision to use a pseudonym so as to protect her identity. Actors were summoned for her fictional documentary images so as to protect actual Ahmadis in the public sphere. By placing herself and some performers in scenes from the everyday, Mehboob begins to subliminally address the violence of our own as well as their psychological conditioning.

“Ammi recently lost her job because of who she is. She was teaching at a boys’ college. Students stopped attending her classes and were planning to go on a strike against her. She thinks the college principal was kind enough to warn her and told her to resign.

I told Ammi she needs to get better at hiding her identity.

She said, ‘all we are left with is our identity. If we don’t own it, there is no reason to live. Losing a job is a small price to pay’.

I think she is being naive”.[7]

A spread from Guftgu – Ahmadi’s of Pakistan (New Delhi: Offset Projects, 2020)

The staged image becomes an act of visualising resistance, by emplacing a fictional element into the narratives of contemporary reality with the artist/practitioner as a witness. The personal echoes the political.

For Mehboob, this is not just a ‘project’ to share with the world but a personal, ongoing concern that continues to expand through her work – as a photographer, filmmaker and archivist.

“For a work of this nature, there is no real end. I see this work extend for another decade or two because it is such a complex situation. It just not just about a political situation but also about lives who I am attached to. My research is slowly becoming the core of my work. From testimonies that I have been collecting over the years, I have now made a secret journal that is shared with members of the community. This is not for the world to see. It is our own safe space”.

Notes

[1] Elizabeth Edwards, ‘Photography and the Performance of History’, Kronos, No. 27 (University of Western Cape, November 2001).

[2] Commission on International Religious Freedom: Annual Report of the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom, 2005, 130.

[3] Nida Mehboob, A Survival Guide for Ahmadi Muslims of Pakistan (Berlin: Akademie der Künste, 2021), 21.

[4] ibid., 65-66.

[5] ibid., 22.

[6] As per Ordinance No. XX of 1984, Anti-Islamic Activities of the Quadiani Group, Lahori Group and Ahmadis (Prohibition and Punishment).

[7] Nida Mehboob, Guftgu –Ahmadi’s of Pakistan (New Delhi: Offset Projects, 2020), 8.

Anshika Varma is a lens-based artist and curator with an interest in personal, collective and mythical histories. Combining her curiosity to study cultural and social evolution with storytelling, her work often looks at the emotional connection between an individual and their environment. Through her work, she seeks to question our relationship with the language of the photograph through experimenting in interactive formats of dissemination. She is the Founder of Offset Projects, an initiative that works to create channels of engagement with photography through publishing and exercises in book-making.

Nida Mehboob is a photographer and filmmaker based in Lahore, Pakistan. She graduated as a pharmacist but left the field to pursue photography. Her documentary work got her into several international workshops and fellowships over the years. She is a Berlinale Talent 2020. Her short films have screened at international film festivals including Locarno Open Doors 2018. Her topic of interests includes themes of social injustice varying from religious and gender discrimination in Pakistan.

Nida Mehboob is a photographer and filmmaker based in Lahore, Pakistan. She graduated as a pharmacist but left the field to pursue photography. Her documentary work got her into several international workshops and fellowships over the years. She is a Berlinale Talent 2020. Her short films have screened at international film festivals including Locarno Open Doors 2018. Her topic of interests includes themes of social injustice varying from religious and gender discrimination in Pakistan.