by Andrea Nelson

Courtesy: Collection of Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg

Life without photographs is no longer imaginable. They pass before our eyes and awaken our interest; they pass through the atmosphere, unseen and unheard…They are in our lives, as our lives are in them. – Lucia Moholy

In her book A Hundred Years of Photography, 1839-1939, photographer and historian Lucia Moholy examined the social impact of medium’s first 100 years.[1] Her analysis focused less on artistic concerns with quality and originality and more on the conditions of photographic production and reception. A position informed by her own marginalisation from the growing discourse surrounding the Bauhaus, a German avant-garde school where her husband, László Moholy-Nagy taught and her labour as a photographer and theorist was too often disregarded.[2] Moholy ends her history with the statement, “Life without photographs is no longer imaginable”, a situation aided by improved rotogravure technologies and the transmission of pictures by wire which had spurred the reproduction of all kinds of photographic images during the first half of the 20th century.

As the circulation and mass appeal of photographs increased after World War I, photography more effectively signified key aspects of modernity, including the iconic figure of the New Woman. Independent and confident, the New Woman was easy to recognise but hard to define. With a short haircut, fashionable clothes, and confident stride she embodied a range of female identities that emerged globally as women transgressed boundaries and sought to expand their rights.[3] The New Woman was, however, more than a marketable image seen splashed across the pages of magazines and projected on the silver screen. She was an inspirational model that evolved alongside major developments in photography. A symbol that intertwines gender with photography, she is a compelling lens through which to view the work of women photographers like Moholy. Although women participated in photography from its inception, it was not until the 1920s, that they entered the field in force. With the rise of mass communications, better access to training, and growing acceptance of their presence in the workplace, women across the globe made an indelible mark on the medium.

The New Woman Behind the Camera – an exhibition I curated that was on view at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York from 2 July to 3 October 2021, and is currently installed at the National Gallery in Washington, DC from 31 October 2021 to 30 January 2022 – examines the work of a diverse group of more than 120 women who made significant advances in modern photography from the 1920s to the 1950s. This production reflects not only their personal experiences, but also the extraordinary social and political transformations of the first half of the 20th century – including two world wars, a global economic depression, struggles for decolonisation, and the rise of fascism and communism. The pioneering efforts of these photographers to gain creative agency and self-representation were part of the broader ongoing struggle to achieve gender equity. Often overlooked, their contributions are key to a more inclusive history of photography.

The New Woman

Known by many names, from nouvelle femme and neue Frau to modan gāru and xin nüxing, the New Woman was a global phenomenon based on real women making revolutionary changes in life and art. To invoke the model of the New Woman is to invite complexity and ambiguity into the study of modern photography. To begin with there is no one New Woman. While conceived in Europe and the United States, her manifestations around the world were based on a constantly changing mix of imagined and lived experience contingent on local histories and culture.[4] As a symbol she represented, on the one hand an economically independent and self-reliant contributor to society, and on the other hand a threat to men’s control of politics and the workplace which relied on conservative definitions of femininity and motherhood. Outside Europe and the United States, the fashionable New Woman who embraced a Western urban lifestyle fueled concerns over unbridled modernity and the threat of foreign influences to national identity, which muddied the struggle for gender equality.[5] Intensely debated, the multifaceted idea of the New Woman helped break down monolithic constructions of gender but did not automatically secure legitimacy or equality. While many women photographers all over the globe drew on or reformulated the ideal of the New Woman as they made sense of their own position in society, others, like Homai Vyarawalla, did not think of herself as a ‘woman photographer’ but rather simply a ‘photographer’. She remarked later in life, “The idea didn’t come to me that I was doing something unusual…something only a man was supposed to do”.[6]

Histories of Modern Photography

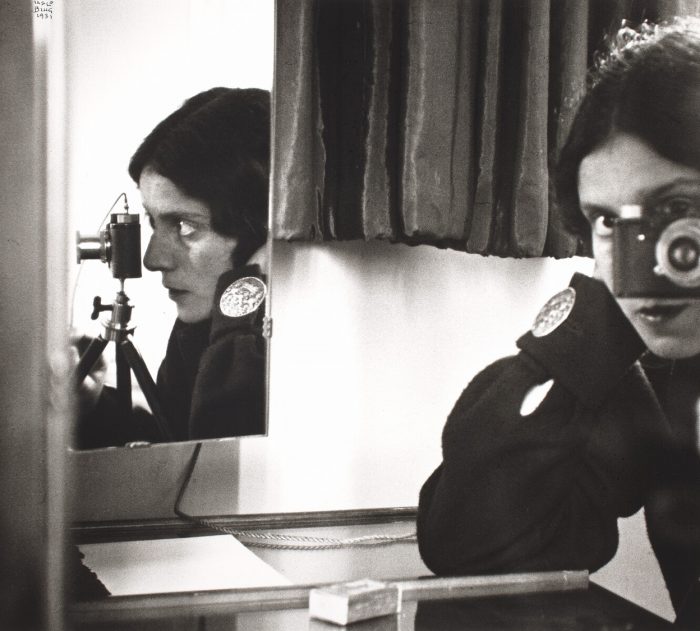

Both the exhibition and the accompanying catalogue mapped out the parallel and intersecting narratives of modern photography that developed around the world through the contributions of women practitioners. Thematic sections organised the analysis beginning with self-portraits and portraits of photographers at work – often featuring the photographer with her camera – and established women as artists and professionals. Some explored their personal identities, presenting themselves as they wished to be seen. IIse Bing’s 1931 Self-Portrait with Leica (Figure 1), for instance, in which we see the photographer both head on and in a reflected profile, exemplifies a carefully crafted and complex understanding of self by this most quintessential of interwar New Women.

Meanwhile, pictures taken by others, in many cases by the photographers’ friends or colleagues, offer rare behind-the-scenes glimpses into the working lives of these pathbreaking artists and visualise the diversity of the new women behind the camera.

Commercial studios were an important entry point into the field for many women as learning photography was a way to work around entrenched barriers to employment and education. Women had been involved in the production of studio portraits from the medium’s earliest days. They hand-coloured and mounted prints, retouched negatives, and served as studio receptionists. Yet by the 1920s, women were running their own businesses in greater numbers and quickly claimed their position behind the camera, reinvigorating the genre of portraiture.[7] A rich history of female-led studios has emerged not only in cities such as Berlin, Buenos Aires, London, and Vienna but also in Osaka and New Orleans. From Palestine and Iraq to India, Turkey, and Korea, studios with women photographers filled a need for an acceptable place for women and children to have their portraits made. Most of these photographers remain unknown, yet one, Karimeh Abbud, stamped her work with her name in both Arabic and English. Abbud often travelled to clients’ homes bringing their own backdrops (Figure 2), which allowed sitters, such as these three women, to pose more privately and comfortably.

Artistic and literary response to the rapid growth of cities was already a well-established genre by the 1920s, yet photography was arguably the ultimate medium for reflecting the urban experience. It froze moments and disrupted linear narratives to describe the city as a modern phenomenon. As an art student in Bombay (now Mumbai), Homai Vyarawalla taught herself photography and quickly forged a successful career using her camera. Working on assignment for the Bombay Chronicle and the Illustrated Weekly of India, she brought a sharp eye to daily life in the city’s diverse communities and to key locations such as the Victoria Terminus (now Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus). The train station, an architectural hybrid testifying to the imposition of European taste on Indian traditions, is usually depicted as a grand spectacle. In her photograph (Figure 3), Vyarawalla diminished its dominance by focussing on the public space outside the building. She positions her camera low to the ground and glimpses the station through the wheels of a carriage that frame a man pushing a cart in the middle ground. Pedestrians and a city bus can be seen in the distance. These modern compositional devices create a dynamic work that is both a study in perspective and camera vision and a fresh interpretation of one of the city’s historical symbols.

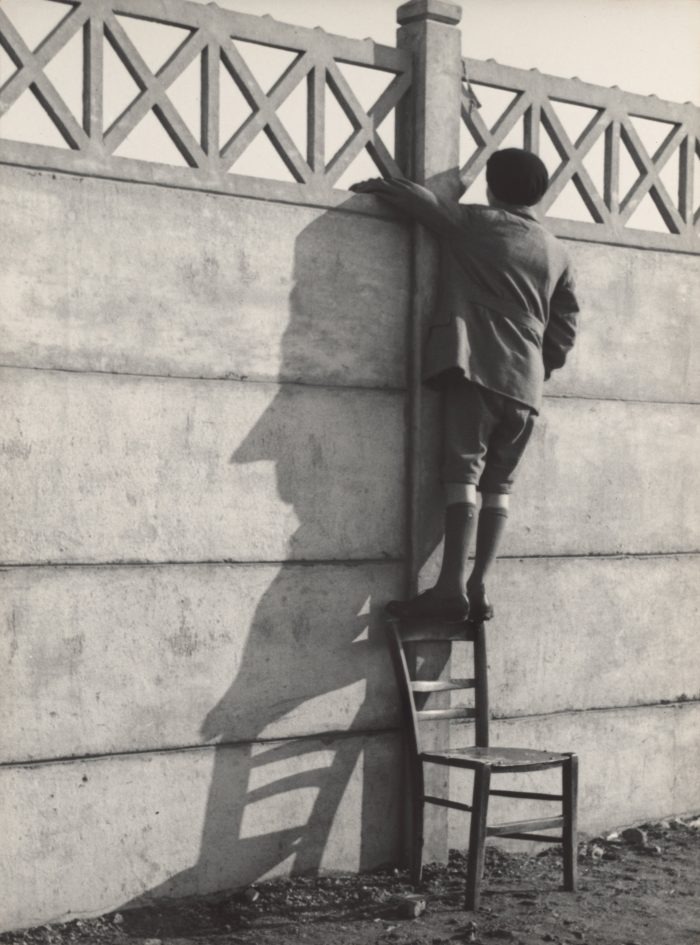

Creative experimentation was central to the artistic flourishing of photography during the 1920s to the 1950s as photographers explored the medium’s inherent characteristics. Using techniques such as photomontage, multiple exposure, and the cameraless photogram, women studied the effects of modern technology on human perception. A new visual language was being advanced by now canonical figures such as Imogen Cunningham and Germaine Krull but also by less known photographers such Anna Barna, whose work was literally rediscovered under a bed in the celebrated photographer, André Kertész’s New York city apartment in the 1980s. The two Hungarian-born artists first met in Paris, where Barna made this playful print of an onlooker casting a surreal shadow (Figure 4).

Courtesy: National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Robert B. Menschel and the Vital Projects Fund

New concepts regarding health and sexuality and changing attitudes about movement and dress indicated the body as a central concern of modernity with striking implications for both women and men. Women photographers produced incisive visions of liberated modern bodies, such as Yvonne Chevalier’s nude-like rendering of an abstracted body that is only suggestive of its gender. Pictures of dancers in motion celebrated the body as artistic medium and revealed close collaborations between women photographers and women choreographers. As key players in the field of fashion photography, women, too, were integral in defining the New Woman as well as cultivating the tastes of recently empowered female consumers.

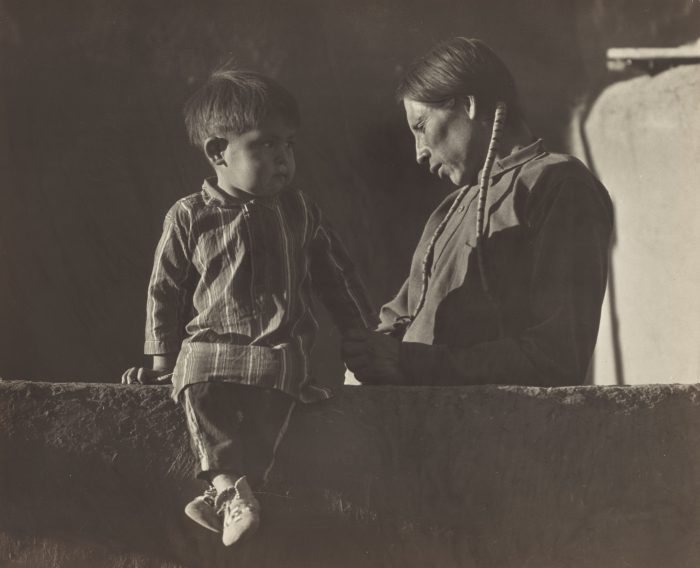

Beginning in the 1920s, numerous women pursued professional photographic careers and travelled extensively for the first time. Many from the United States and Europe took photographs that documented their experiences abroad in Africa, Asia, and elsewhere, while others engaged in formal ethnographic projects supported by their home countries. Working for the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs, Marjorie Content produced sensitive portraits of members of Indigenous tribes as seen in her portrait of Taos Pueblo dancer Adam Trujillo with his young son (Figure 5). While gender may have afforded certain opportunities, such as access to areas that were off limits to their male counterparts, it did not exempt women from portraying hierarchical views of race and other forms of discrimination in their photojournalistic, ethnographic, or humanitarian photography.

Courtesy: National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Purchased as the Gift of the Gallery Girls, © Estate of Marjorie Content

Photojournalism was a dominant form of communication during this period and women photographers expanded the reach and influence of the medium with their visions of a complex and rapidly modernising world. During a time of worldwide economic instability and political extremes, they produced arresting images of the human condition. Whether hired by government agencies or working independently, women contributed profoundly to the visual record of the Depression and the events leading up to and following World War II, defining what would become social documentary. Women often received the so-called ‘soft assignments’ of photographing the home front and were assigned stories that focused on women and children. Yet as we see with the work of Jewish photographer Emmy Andriesse who worked underground in Nazi-occupied Amsterdam, this could be incredibly dangerous. A small number of women, such as Galina Sanko and Gerda Taro, worked and even lost their lives close to the front lines. Devastating images of recently liberated concentration camps like those by Lee Miller and Margaret Bourke-White soon gave way to the realities of the post-war era as recorded by Tsuneko Sasamoto in her street snapshots of Tokyo as well as this moving photograph of the Hiroshima atomic dome during a lantern ceremony (Figure 6).

Courtesy: Tsuneko Sasamoto / Japan Professional Photographers Society

In countries such as India, Japan, and China, photojournalism during this period was just emerging as a viable profession for women. One remarkable example is Niu Weiyu, who had a long career working for the major news agencies of the newly formed People’s Republic of China (Figure 7).

Modernity’s Global Context

Women were a driving force in modern photography. Yet the challenges they faced on their path to becoming photographers compound the problems historians face with evaluating work that has disappeared from the historical record. Details of the biographies of many of these photographers have been lost, along with the prints they made that were destroyed or negatives that were never processed. The careers of some were cut short by the expectation that they assume all childrearing and domestic responsibilities after marriage. Other paths were truncated, like their male colleagues, by political exile, wartime atrocity, and post-war censors. Still others have been disregarded because the kind of photography they practiced – including commercial studio portraiture, fashion work, and advertising. And, finally, masculinist histories of the field have downplayed women’s contributions, however substantial, to the visual culture of the time.

The ultimate aim of The New Woman Behind the Camera was to not merely insert new or forgotten figures into the canon but, more importantly, to complicate and enrich our understanding of modernity. Women of course constitute a heterogeneous group whose identities are defined not only by gender but also by race, class, ethnicity, religious affiliation, cultural values, and individual personality. Yet it is incontestable that gender was a determining factor for most if not all these photographers, and that their everyday lives and the reception of their work were circumscribed by culturally variable definitions of femininity that were often marked by sexism.

The New Woman Behind the Camera emphasised the importance of women’s agency and the specificity of global contexts to propose a history of modern photography that decenters the Euro-American narrative and recognises difference. Feminist scholars and activists have long demonstrated that museums are gendered spaces in which women’s cultural production and history have been underrepresented and oversimplified. Because the permanent collections of the vast majority of museums remain heavily weighted toward male artists, all-women exhibitions have been an effective strategy for raising awareness of gender disparity and prodding cultural institutions toward equity. As curators and scholars continue to bring forward women’s creativity and to examine the relationships, collaborations, and collective undertakings of women photographers around the globe, our vision of photography’s history is bound to become sharper, more nuanced, and hopefully, even more inspiring to future generations.

[1]Moholy, Lucia. A Hundred Years of Photography, 1839-1939. London: Penguin Books, 1939, 178.

[2]For more information on Moholy see Jordan Troeller, ‘Lucia Moholy’s Idle Hands,’ October 172 (Spring 2020), 68-108.

[3]See Alys Eve Weinbaum, Lynn M. Thomas, Priti Ramamurthy, Uta G. Poiger, Madeleine Yue Dong, and Tani E. Barlow, eds., The Modern Girl Around the World: Consumption, Modernity, and Globalization. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008, and Elizabeth Otto and Vanessa Rocco, eds., The New Woman International: Representations in Photography and Film from the 1870s through the 1960s. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2011.

[4]Felski, Rita. The Gender of Modernity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995, 146. Felski notes that the term ‘New Woman’ was coined in 1894 by Irish writer Sarah Grand.

[5]Aida Yuen Wong, introduction to Visualizing Beauty: Gender and Ideology in Modern East Asia, ed. Aida Yuen Wong. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2012, 5.

[6]See the film, Homai Vyarawalla, courtesy of SPARROW (Sound & Picture Archives for Research on Women), Mumbai, India. Sabeena Gadihoke’s India in Focus: Camera Chronicles of Homai Vyarawalla (Parzor Foundation and Mapin Publishing, 2006) is a major resource on Vyarawalla’s life and career.

[7]Of course not all women could just decide to pick up the camera, whether as a profession or as a means of personal expression. To do so required a level of self-determination as well as the financial means to purchase equipment.

Andrea Nelson is associate curator in the department of photographs at the National Gallery of Art, Washington. She received her Ph.D. in art history from the University of Minnesota in 2007 and has published on modern and contemporary photography and the history of the photobook. She also serves as cochair of the museum’s Time-based Media Art Working Group.