Text and Images by Sohini Sen

To a photographer, the Himalayas are a hidden treasure house of luxuriant landscapes and rich history. However, the experience of women travellers and photographers on the ranges is also about how women cope with ‘being women’ in an unfamiliar and rugged terrain.

In the early twentieth century, Frenchwoman Alexandra David Néel walked from China across Tibet and into the forbidden city of Lhasa, disguised as a beggar. Isabelle Eberhardt travelled, dressed as a man, extensively across North Africa.

While we do not disguise ourselves as men, my travelling companion Sumita and I do prefer androgynous attire: it draws less attention. As a two-woman team renting a car, we are often on an unfamiliar, solitary road with one unknown male driver. Any of the drivers – locals – could pick up their friend on the way, and we would lose the 2:1 advantage and God knows what else with it.

What began as an ambling among the Himalayan ranges slowly grew into a ‘magnificent obsession’ with the youngest and the most tumultuous mountains in the world. We continued travelling – for ten long years and over ten thousand kilometres – from the west to the east of India, from Ladakh to Arunachal Pradesh, to soak in the majesty of it all. We had an eye for the aesthetic, a heart for the exotic, and an ear for the local lore. The fine patchwork quilt of images that emerged, woven with the gossamer threads of personal experience and history, went on to become my travelogue-memoir Zanskar to Ziro: No Stilettos in the Himalayas (Niyogi Books, 2018).

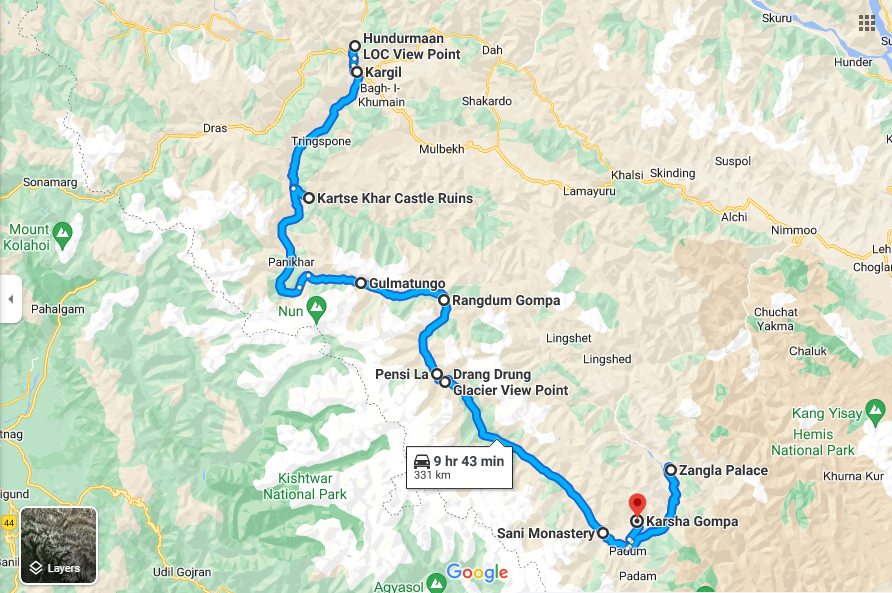

Our fortnight-long journey into the remote Suru and Zanskar river valleys of Ladakh in July 2013, presented in this essay, is one of the brightest patches in that quilt. It began at the Line of Control (LoC), Kargil.

LoC, Hunderman-Brok

But for the call of the chungkas (red-billed choughs) circling over the sheer, barren cliff faces and the gushing Suru River flowing thousands of feet below, the ranges are silent, inviolate.

Only when the late morning sunlight falls directly on the peaks, a keen eye may discover specks of white canvas on the summits, and the occasional orange-green flutter of a flag.

For they stay up there: young men in fatigues living out of hidden bunkers and tents in often sub-zero temperatures and rarefied air, to protect an undrawn line between two restive nations: India and Pakistan.

The teal-green Suru River does not respect lines of control. It crosses the LoC with ease and flows into Pakistan.

Operation Vijay, the Indo-Pak war of 1999, has named these forbidding Himalayan peaks not by their altitude, but by the battles fought over their recapture: Rhino Horn, Batra Top, Tiger Hill, Tololing.

It is not a happy place, this war-ridden Indian village of Hunderman-Brok. The Pakistani villages on the other mountain range are identical though – down to the tall, light green poplars and the deep green-and-silver domes of mosques. Pakistani soldiers may even be spotted at an impromptu game of cricket. But a signboard warns the visitors of landmines on neighbouring slopes. Our driver talks of random rifle shots and shelling from the Pakistani side. His tone is hushed.

The teal-green Suru River does not respect lines of control. It crosses the LoC with ease and flows into Pakistan.

Suru Valley

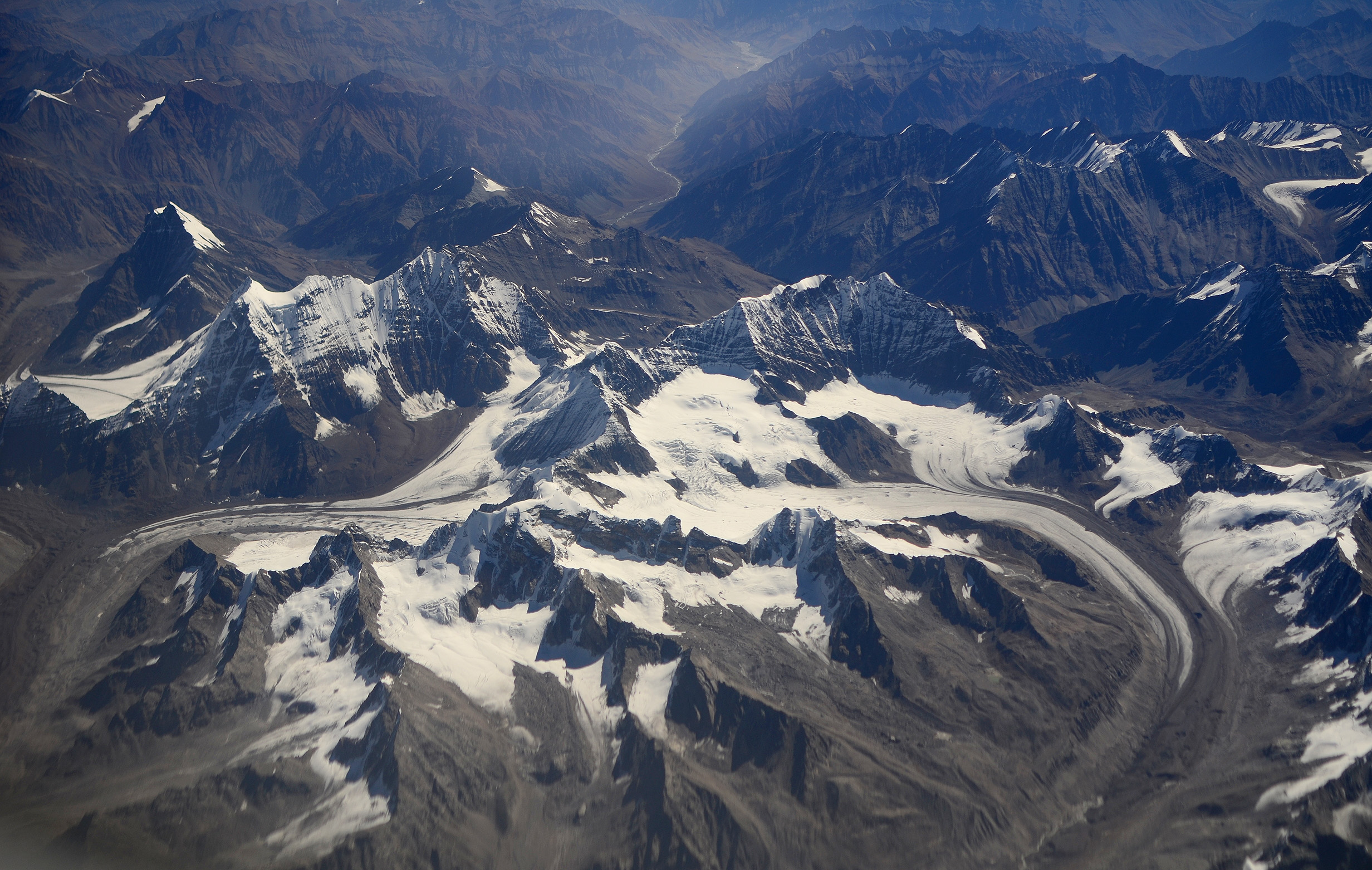

Driving down the Kargil-Zanskar road that cuts through the Great Himalayan Range and the Zanskar Range, we are tracing Suru to its origin, the Pensi La glacier.

It is a smooth drive at first, on a tar road that runs parallel to the bubbling Suru River; rows of tall green poplars that stand not in one another’s shadow; stunted, yellow-leaved willows punctuated by sweet briar hedges loaded with red fruit; the lush, almost luminescent, green fields of model village Trespone; and the detour into Kartse Khar village to see the ancient, seven metre rock-cut sculpture of Maitreya Buddha.[1]

There is an abundance of white peaks and glaciers towards the cornflower-blue horizon. The snow-covered twin peaks Nun (7,135 metres) and Kun (7,077 metres), separated by a four-kilometre-long white plateau, tower over a widening river where men fish with light blue nets.

The Suru leads us along its valley, to majestic views of snow-loaded peaks. The first ascent of Rungofarka (or Techafarka, 6,495 metres) by the north ridge was by Alan Rousseau and Tino Villanueva in October 2017.

Pinnacle Peak (now called Lingsarmo) at nearly 7,000 metres was where American Fanny Bullock Workman (1859-1925), geographer, cartographer, explorer, climber and travel writer, set an early altitude mountaineering record for women in 1906.[2]

Autumn has preceded us here in the valley with a palette of sunset hues. While the mountain peaks are laden with fresh snow, the Aconogonum tortuosum streaks the lower slopes with a bright, powdery orange, the meadow bistort is sending up tiny spikes that are a deep shade of maroon, and among the riotous orange and red bushes walks a lone, ebony-black horse. The Suru is blue, taking its colour from the clear blue sky, and sheep grazing by it are a pale brown, just the colour of the boulders.

This is the Gulmatungo region. It could easily pass as a painting by French Impressionist Claude Monet.

Rangdum Village and Monastery

We are close to Rangdum village. Rangdum Monastery, founded in 1783, sits on a knoll (4,031 metres) overlooking an amphitheatre-shaped valley enclosed by tall, striated ranges.

The Nun Kun Deluxe Camp is a cluster of twenty tents squatting at the base of the Rangdum Monastery. We are the first to arrive this evening. The sun goes down, and with the twilight the mountains turn dull, forbidding. The wind is freezing. The walk to the dining tent for a hot cup of tea or to charge my camera battery is only slightly uphill, yet I find myself straining hard to breathe. It is not normal.

By 9 pm, despite the prophylactic Diamox, I have extreme difficulty breathing. I am nauseous, irritable. Talking is an immense effort. The normally snug woollen cap on my head feels tight as a noose.

This is cerebral oedema, a manifestation of Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS).

To confirm, I try to walk on an imagined straight line: right heel before my left big toe, then left heel before the right big toe. Each foot should point forward while I walk.

I fail the ‘tandem gait’ test. My coordination is seriously impaired. I need to travel to a lower altitude immediately. We are seven hours away from Kargil. Our driver has gone, with the car, to find a village homestay. There is no mobile network.

It is a beautiful night. A brilliant moon and rings of large, glistening stars hang low in the cloudless sky. The valley is bathed with radiance, rivulets shine like silver yarn. It is a night for time-lapse photography, of sitting outside the tent on the low, folding canvas seats in silence and harmony.

Instead I sit huddled inside the tent, clutching my freshly-charged camera battery in my palm to keep the charge from draining.

Fortunately, a birdwatcher group has checked in, and their leader offers me a portable oxygen can.

After 10 pm, the lone light in the tent goes off with the generator. The moon slips behind the mountain. There is not even a pinhead of light in the entire valley. In the light of a head torch, I prise open the seal of the oxygen can with a key. Inhale. It should have ten litres of the life-saving gas, but it finishes rapidly with my anxious deep breaths.

It is our longest night.

The first light of dawn has never been so welcome. I feel almost normal. While we wait for our car I perch on a low seat just outside the tent. The sunlight feels good. White Wagtails and Black Redstarts are trotting close to my feet.

Sumita watches me watching the birds. ‘Don’t you wish to take photographs?’ It seems an effort to go into the tent, get my camera. ‘I will just look at them.’

‘Zanskar Valley is more remote than Suru Valley,’ Sumita says, ‘do you feel up to the journey?’

It is a tough decision, reckless too. We still decide to go on.

While leaving the camp, we soberly recall how ethno-religious violence in 2000 had led to the killing of four young lamas at the Rangdum Monastery.[3]

Zanskar Valley

This is no road, this dull grey, moraine-strewn, undulating track that at regular intervals is interrupted by narrow, gushing rivulets born of glacial melt.

Merciless, nose-clogging, camera-ruining sheets of red dust rise on either side of us and rush in through every infinitesimal gap in the car. The scorching heat makes it quite hard to believe that we are at great altitude, that this is September, and that the pass we just crossed, the prayer-flag-draped Pensi La (4,400 metres), would soon be covered in snow and closed for eight odd months.

When the Drang Drung glacier (altitude 4,780 metres, length 23 kilometres) of the Zanskar Range on our right reaches almost down to the road, it is a welcome distraction and a chance for a photo break.

On any normal road, these 130-odd kilometres from Rangdum in Suru Valley to Pibiting village in Zanskar Valley should not take us seven hours. On any normal road that takes seven hours to cover, one should find a washroom and a tea-shack. Yes, even in the hills.

The road to Zanskar has nothing.

‘Madamji, washroom jayenge? (Madam, would you like to visit the washroom?)’ our driver asks. He is not joking. He has spotted some large boulders by the road, and this is where we make use of the privacy they offer.

We drive on through the rows of Padum’s nondescript houses to the quieter village of Pibiting, with its traditional houses and the tiny monastery perched on a hillock, and check in at Omasila Hotel.

Zanskar Valley has seen a lot of progress. At dinner, hotel-owner Norbu’s father shares old tales. ‘We did not even know what a pressure cooker was. Someone had got hold of one, and put it on a stove. When the cooker started letting off steam, a villager thought there was a spirit inside it. He took a long pole, stood at a safe distance, and smashed the lid! But now, children study. Education is important.’

Palaces of Zangla

Zanskar has had its own kings. At 3,931 metres, Zangla village is some thirty-seven kilometres from Pibiting. From the evidence of petroglyphs found throughout the territory, settlements can be traced back to the Bronze Age.[4] Zangla has not one, but two royal palaces.

Sonam Tundup Namgyal, the last titular ruler of probably one of the tiniest kingdoms in the Himalayas, died in 1987.

Stanzin, the granddaughter of the last ruler, shows us a rare photograph of Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru with Kushok Bakula Rinpoche, believed to be a reincarnation of one of the sixteen arhats or disciples of Lord Buddha,[5] and India’s first ambassador to Mongolia.[6]

Through traders and pilgrims, Lama Rinpoche had come to know about the massive build-up of Chinese troops in Western Tibet in April 1962, and had informed Nehru of the impending attack on Ladakh. His message was ignored.

A hot and tiring climb up some 200 steps from the valley floor takes us to the ruins of the Old Zangla Palace. In one of the rooms in this mud-brick building that offers fascinating views of the Zanskar River and its entire valley far below, Hungarian scholar Alexander (Sándor) Csoma de Kőrös[7] compiled the first Western dictionary of the Tibetan language in 1823.[8]

Sani Kani Khar

The sprawling compound of Sani Kani Khar (the Sani Monastery) is close to Padum, with an assortment of chortens (a Buddhist shrine, typically a saint’s tomb, or a monument to the Buddha) and a two-storeyed building that date anywhere between the second and the seventeenth centuries. The oldest chorten on the grounds is the Kanishka Stupa[9] built by the Kushan Emperor Kanishka in the second century. One of the holiest Buddhist sites of that era, the six-metre reliquary stands behind the main building, but no markers highlight its significance in Buddhist history.

Karsha Monastery

With whitewashed buildings scrambling halfway up a rust-coloured rock face in an intricate labyrinth of monks’ quarters and prayer halls, Karsha is Zanskar’s largest monastery and one of its most ancient. Even though it dates back to the tenth century, the monastery came into prominence only around the fifteenth century.

Some of the sanctum’s shelves have awkward empty spaces.

‘When the Pakistanis attacked,’ a lama tells us, tracing our glance, ‘they burnt some of our holy scripts.’

He points to a large silver-plated chorten decorated with semi-precious stones. ‘They broke this chorten, too, and took away the stones and the silver. But the body was undamaged.’

‘Body? Whose body?’

The chorten has a small glass front with an ornate copper frame. We now notice the profile of a man seated inside.

It is the mummy of Rinchen Zangpo (958-1055 AD).[10]

‘When the chorten was renovated after the Pakistani attack, the body was taken out,’ the lama continues, ‘and the fingernails were still growing.’

The sight of the sacred mummy triggers my curiosity about Tibetan concepts of the body, and about sowa rigpa (Tibetan holistic healing).[11] We approach the hundred-year-old amchi (traditional practitioner) who lives at the base of the Pibiting Monastery.

‘Do you make the medicines yourself?’ I ask. Our driver translates.

‘I make with local herbs and other ingredients. I cannot divulge names.’

‘Check my pulse, please,’ I tell the old man on an impulse, extending my left arm.

‘No, not that hand. Show me your right hand,’ the amchi says.

‘He believes men have their heart on the left side of the body, and women have theirs on the right,’ his sceptic son pipes up.

The amchi feels my pulse, and then says, ‘Your pressure is low. You are feeling dizzy, and you have a headache.’

He has diagnosed right. The Grim Reaper had come visiting me in Rangdum, and I am still recovering.

Here is the thing, though: since I live to tell the tale, I just might be called a carefree, adventurous soul. If I did not, I would be summarily dismissed in social conversations as a foolhardy woman who had it coming.

Sobering thought, that.

Notes

- Jan Fontein, “A Rock Sculpture of Maitreya in the Suru Valley, Ladakh”, Artibus Asiae 41, No. 1 (1979), p. 6. https://doi.org/10.2307/3249497

- Alan Rousseau, Rungofarka: The First Ascent of a Difficult 6,500-Meter Peak (American Alpine Club Publications, 2018), p. 4.

- Praveen Swami, “Murder in Leh”, Frontline (22 July 2000). https://frontline.thehindu.com/other/article30254576.ece

- Orsolya Szabó and Anna Szeredi, “Archaeologists on the Top of the World – Hungarian Assessment Work in the Himalayas”, Hungarian Archaeology E-Journal (Autumn 2016), pp. 39-50.

- Nawang Tsering Shakspo, “The Role of Incarnate Lamas in Buddhist Tradition: A Brief Survey of Bakula Rinpoche’s Previous Incarnations”, The Tibet Journal, Vol. 24, No. 3, (1999), pp. 38-47. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43300761

- D. Enkhbayar, A Visionary Monk and a Statesman: In Commemoration of the 91st Birth Anniversary of HH Bakula Rinpoche (Ulaanbaatar: Pethub Buddhist Center, 2008), p. 35.

- Bernard Le Calloc’h, “Alexander Csoma De Koros, the Heroic Philologist, Founder of Tibetan Studies in Europe”, The Tibet Journal, Vol. 10, No. 3 (1985), pp. 30–41. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43300177

- Nawang Tsering Shakspo, “Alexander Csoma De Koros in Ladakh”, The Tibet Journal 10, No. 3 (1985), p. 43. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43300178

- Mohammad Ajmal Shah, “Early Historic Archaeology in Kashmir: An Appraisal of the Kushan Period”, Bulletin of the Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute 72/73 (2012), p. 214. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43610698

- Tsepak Rigzin, “Rinchen Zangpo: The Great Tibetan Translator (958-1055 AD)”, The Tibet Journal, Vol. 9, No. 3 (1984), pp. 28-37. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43302189

- Geoffrey Samuel, “Introduction: Medicine and Healing in Tibetan Societies”, East Asian Science, Technology and Society: An International Journal, Volume 7, Issue 3, Taylor & Francis Online (1 October 2000), pp. 335-351. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1215/18752160-2333224

Sohini Sen was an Assistant Editor with The Telegraph, and a Senior Manager and the Head of Tata Consultancy Services Ltd’s Technical Communication team in Kolkata. Now a full-time travel writer and photographer, instead of chasing deadlines, she gets chased by camera-shy yaks, and was once ceremoniously kissed by a dolphin. She has also had the unique experience of seeing three Rafflesia flowers – the largest flowers in the world with 30-inch diameters – in bloom. She survived two severe Acute Mountain Sickness attacks at the high altitudes of Gurudongmar Lake, Sikkim and Suru Valley, Ladakh, and wonders how her brain still functions reasonably well. Sen is the author of The Talking Table and Other Stories (Shishu Sahitya Samsad, 2012), Yatra Pathe Rabi (Ananda Publishers, 2014), Ladakh: A Photo Travelogue (Niyogi Books, 2016), Zanskar to Ziro: No Stilettos in the Himalayas (Niyogi Books, 2018), and a collaborative photo-book named Invincible City (Penprints Publications, 2023).

Sohini Sen was an Assistant Editor with The Telegraph, and a Senior Manager and the Head of Tata Consultancy Services Ltd’s Technical Communication team in Kolkata. Now a full-time travel writer and photographer, instead of chasing deadlines, she gets chased by camera-shy yaks, and was once ceremoniously kissed by a dolphin. She has also had the unique experience of seeing three Rafflesia flowers – the largest flowers in the world with 30-inch diameters – in bloom. She survived two severe Acute Mountain Sickness attacks at the high altitudes of Gurudongmar Lake, Sikkim and Suru Valley, Ladakh, and wonders how her brain still functions reasonably well. Sen is the author of The Talking Table and Other Stories (Shishu Sahitya Samsad, 2012), Yatra Pathe Rabi (Ananda Publishers, 2014), Ladakh: A Photo Travelogue (Niyogi Books, 2016), Zanskar to Ziro: No Stilettos in the Himalayas (Niyogi Books, 2018), and a collaborative photo-book named Invincible City (Penprints Publications, 2023).