Text and Images by Senani Dehigolla

I believe that to take a photograph is to face one’s truth, to pay attention to what is otherwise forgotten, to freeze a slice of time, and to create a portal into the past. When I look back at early images of protest and resistance, I see generations of struggles captured by numerous photographers curating a visual history of our world. In Sri Lanka, politicians often use mythologized fractions of archaic history to polarize communities, seize and reinforce political power and mobilize memory as an instrument of politics in the present. The ‘politics of memory’ is often manipulated in the acquisition of power, and the collective memory of the past manipulates and influences public consciousness. Seventy-five years on from Independence, the visual history of Sri Lanka’s dark past of civil wars, insurgencies and state repressions provides a glimpse into the horrors of the republic that seems to dominate the current moment.

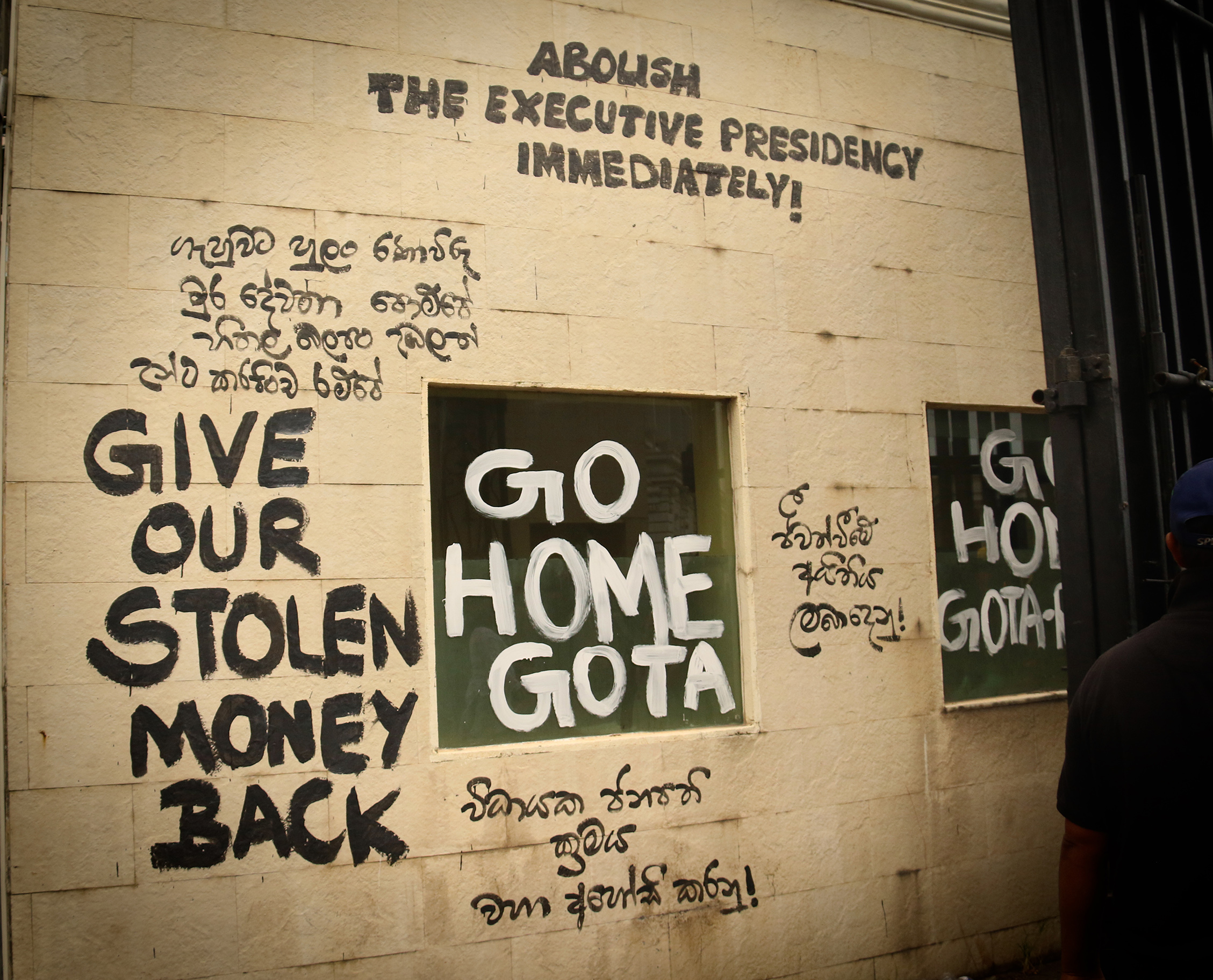

As Lenin so eloquently stated, ‘There are decades where nothing happens, and there are weeks where decades happen.’[1] The weeks leading up to 9 July 2022 constitute one of those historical inevitabilities. On a hot summer’s day in July, protesting multitudes reached the capital city of Colombo, gathering in tens of thousands despite the armed forces’ efforts to break up the crowds. This was also the day I realized the power of people and of photography. Mass protests took place in Colombo demanding President Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s resignation as head of state. The people on the streets expressed their rage against state neglect and mass suffering related to the drastic shortage of a host of basic necessities ranging from food, fuel and crucial medicines to long hours of power cuts; the people’s rage was also against financial mismanagement, and unconscionable political and economic corruption which enabled lavish lifestyles for those in power, supported by the military establishment.

Through photographing this experience, I witnessed disenfranchised people metamorphosing into empowered citizen-subjects; I also witnessed a paradigm shift in the public perception of power. The lessons learned from Aragalaya will last for generations.

I reached Colombo from Kandy on the evening of 8 July as many, including myself, feared that the transportation services would be halted. Soon, trains and other modes of public transport were declared ‘out of service’, preventing many who wanted to participate in the protests the next day from entering the city. Travelling within Colombo was also harder than usual. A large number of people, including myself, had to take whatever modes of transportation were available, trucks, lorries, tuk-tuks,[2] etc., or had to reach their destination on foot.

The Inter-University Students’ Federation,[3] with its fair share of experience in grappling with armed authority over the years, successfully tackled the counterinsurgency methods of the security forces stationed at vital entry points to Central Colombo. The students carefully planned the removal of the barriers at these points on the evening of 8 July. This strategy became a crucial turning point for the resistance as it gave the protesters a head start. The army’s hyper-vigilance failed that night, as the dawn ushered an element of surprise that no state intelligence could have predicted. Thousands of people converged as the mass swelled into the largest unified protest in Sri Lanka.

Facing despotic, intractable authority is to face asymmetric brute force. The strategic occupation of the President’s House was aimed at prising open and exposing injustices from behind closed doors of the establishment and thus testifying to the mass public suffering of the past many months. The storm clouds of repression – much like the tear gas attacks – were omnipresent, and to navigate through them was to expose oneself to a violent nightmare. Contrary to the expectations of those in power, the demonstrators creatively addressed these attacks. They mastered the art of street fighting to protect not only themselves but also others – fellow protesting strangers now became companion activists. One way to manage the tear gas bombs was to use street cones as shields, an improvised low-cost defence mechanism against the might of the Sri Lankan forces. Wearing swimming goggles and tear gas masks, protesters used the most fundamental tactics, which included rallying groups and occupying multiple locations simultaneously, staying constantly vigilant, and putting an escape route in place when facing a barrage of tear gas from the other end of the street.

For me, 9 July for me was a cathartic experience – an opportunity to understand the actual situation, a truth that needs to be reconstructed from the ground up, just as the corrupt political system needs to be totally dismantled. It offered a flicker of hope against the authoritarian lie of a better future, with citizens taking control of a narrative that could have been distorted to serve future propaganda. The most emancipatory realization was that non-violent methods are far superior to the state’s vicious methods, especially if the strength of a state lies in its monopoly on violence. I personally do not believe that the impact and influence of the Aragalaya (Sinhala: ‘the struggle’)[4] reached a crescendo and ended the very same day after the appointment of Ranil Wickremesinghe as the ninth President of the Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka. He was also a staunch supporter of the previous regime. I wonder whether the mobilized strength and coordination of the resistance needed greater maturity and leadership. However, our act of civil disobedience certainly affected the public psyche as citizens have now realized that politics cannot be left only to the politicians – a learning that could potentially change the lives of many.

In trying to capture the front lines of this mass demonstration, I realized how photography can serve as a medium of delivering justice through the documentation of the rare instances of an immense political upheaval. Capturing history as it unfolds is to participate in that making of history, to influence public opinion and to build political consciousness, as well as to contribute to the collective remembrance of injustices and the recording of citizen victories. Photography, if deployed sensitively, can shape a visual timeline of progressive social movements so that future generations can better understand their past. Even more than its political impact as a people’s movement, I feel that the biggest success of the Aragalaya was its infusion of a sense of national unity and identifying oneself with fellow citizens despite social differences. Our struggle brought together a vibrant group of people from all walks of life, representing various professions and, most notably, an amalgamation of different ethnic backgrounds. In earlier Sri Lankan history, such a union has been considered blasphemous. Strengthened and emboldened by this radical coalescence, our unique people’s movement actively exposed and pushed against the vengeful systems of control embedded in the larger security apparatus. It confronted the hegemonic foundations of power, force, and the politics of greed – at least in the context of the struggle itself – thereby briefly liberating Sri Lanka’s democratic potential.

Through photographing this experience, I witnessed people metamorphosing into empowered and responsible citizens. I also witnessed a paradigm shift in the public perception of power. Days and months of hard work by many brave individuals not only came to fruition on 9 July but also contributed to potentially configuring the future. The lessons learned from the Aragalaya will last for generations. Yet to this day, there have been wide-ranging arrests and prosecutions of protesters and leaders of the struggle. Further, the expansion of judicial powers in order to more easily persecute citizens exercising their basic human rights has also been gaining momentum.[5]

These visual markers of the Aragalaya are testament to the impact of people’s movements and their capacity to demand and affect social and political progress. (More) Power to the people!

Notes

- The source of this quote is contested, but it is generally attributed to Vladimir Lenin.

- These motorized three-wheeled vehicles are a popular mode of public transportation in countries such as Thailand, India and Sri Lanka.

- The Inter-University Students’ Federation (IUSF) is a confederation of student unions across Sri Lanka.

- The Aragalaya was a series of mass protests that started in March 2022 against the corrupt state.

- Human Rights Watch, “‘In a Legal Black Hole’: Sri Lanka’s Failure to Reform the Prevention of Terrorism Act”, 7 February 2022, https://www.hrw.org/report/2022/02/07/legal-black-hole/sri-lankas-failure-reform-prevention-terrorism-act.

Senani Dehigolla is a New York-based researcher focusing on conflict and security issues, the gendered consequences of armed conflict, and humanitarian crises. She has conducted extensive research in northern Sri Lanka and East Africa on women’s civic and political participation in peacebuilding, post-conflict economic recovery, and DDR (Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration) programmes. She holds a Masters from the Julien J. Studley Graduate Program in International Affairs at the New School, New York. Her photography interests range from photojournalism to nature and street photography.