Suryanandini Narain

A photo, even a good one, tends to simply show you what something looks like. But if you sequence several of them, in a book, say, or an exhibition, you see not only what something looks like, but how someone looks. – Teju Cole[1]

‘How We See’ can be asked of any of the three participants who experience a photograph: as theorized by Roland Barthes, these are the photographer as ‘Operator’, the subject as ‘Spectrum’ and the viewer as ‘Spectator.’[2] Bound by an unstable power dynamic, they differentially determine ‘how’ they ‘see’ the world and are, in turn, seen by it.

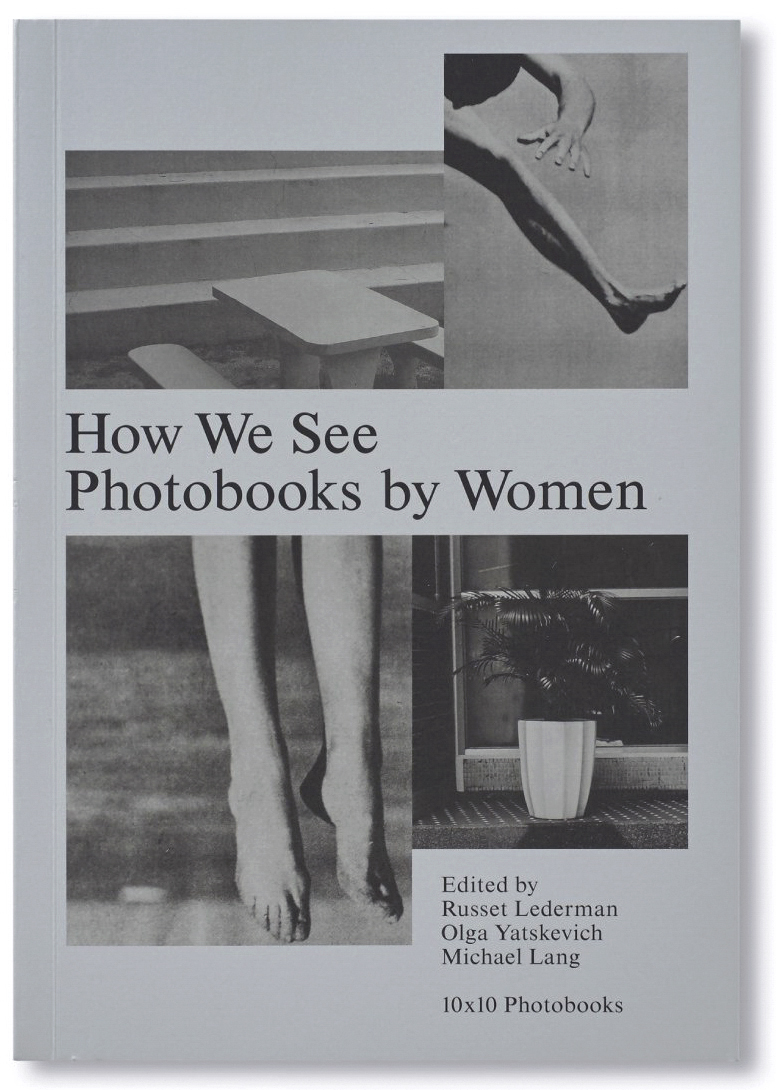

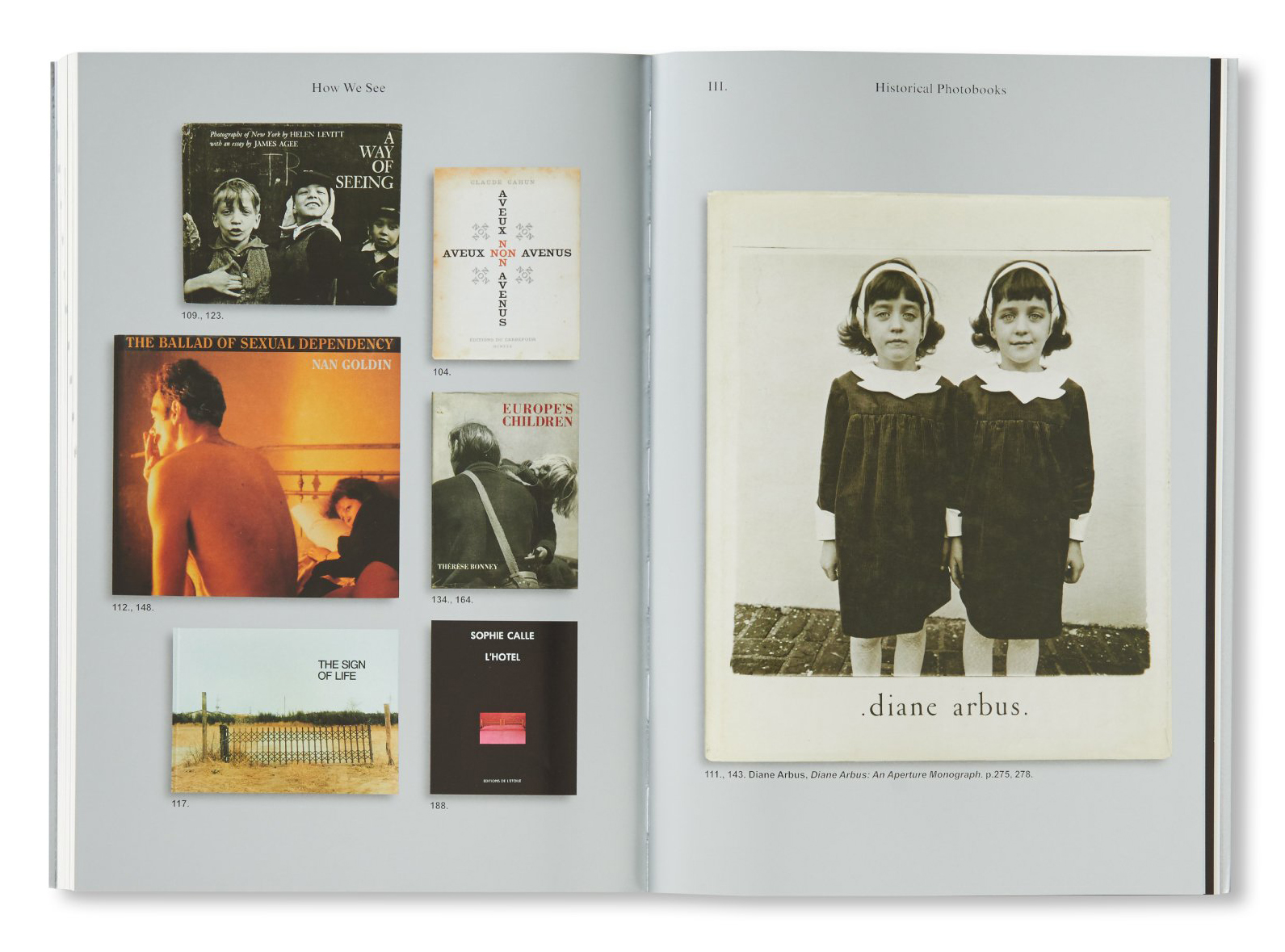

Through the title of their study, Russet Lederman, Olga Yatskevich and Michael Lang, the editors of How We See: Photobooks by Women (10×10 Photobooks, 2018), further destabilize any predictable making of meaning by hinging the experience of photography on gendered identity. They bring the question to the Barthesian triad of contemporary women photobook makers, subjects and viewers, to construct an internal exchange of gazes. In its premise, their archive grounds the fact that how we see photobooks made by women is inherently different from how we see those made by men. A twin publication, What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women (2021), edited by Lederman and Yatskevich, affirms this claim, implying that the very world women view or are viewed in has been historically marked by gender difference. The books undo the scholarly and public neglect of hundreds of photobooks authored by women since the camera’s inception. With rich image reproductions, detailed textual descriptions are offered in regional subsections in How We See and in a chronological arrangement in What They Saw. The publisher, 10×10, supplemented these books with a touring reading room and public programmes across the United States, South America and Europe, thus allowing access to the material. At a time when normative binary conceptions of gender are being challenged in cultures across the world, these two publications are a re-examination of long-held personal beliefs and socially entrenched values that continue to divide us. How We See is uniquely focused on photobooks made by women, as compared to previous and later publications on women photographers per se.[3]

Women photographers and photobook makers have gone far beyond the concerns of gender in their work, even though their relegation into oblivion is mostly due to their own female identity.

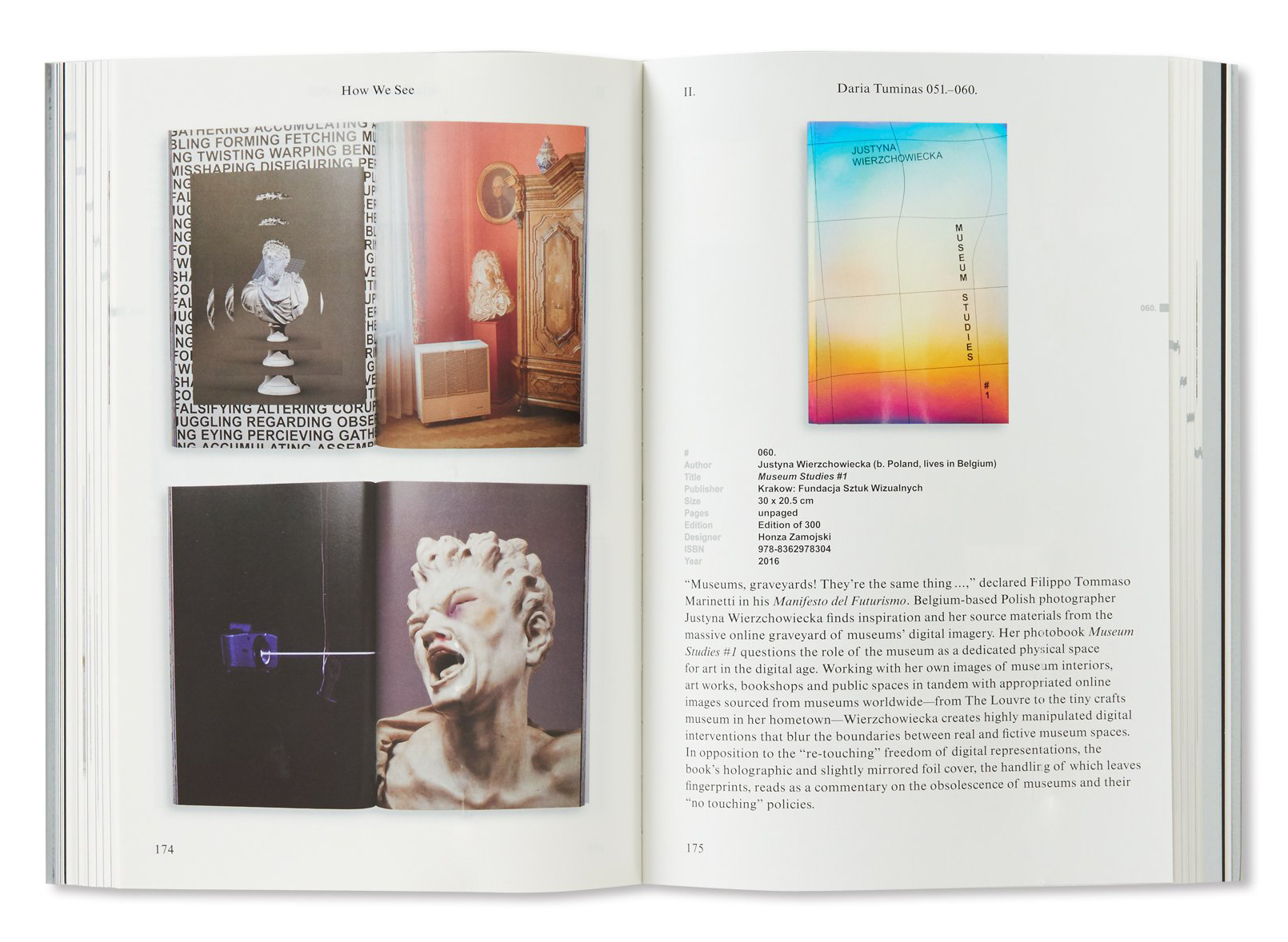

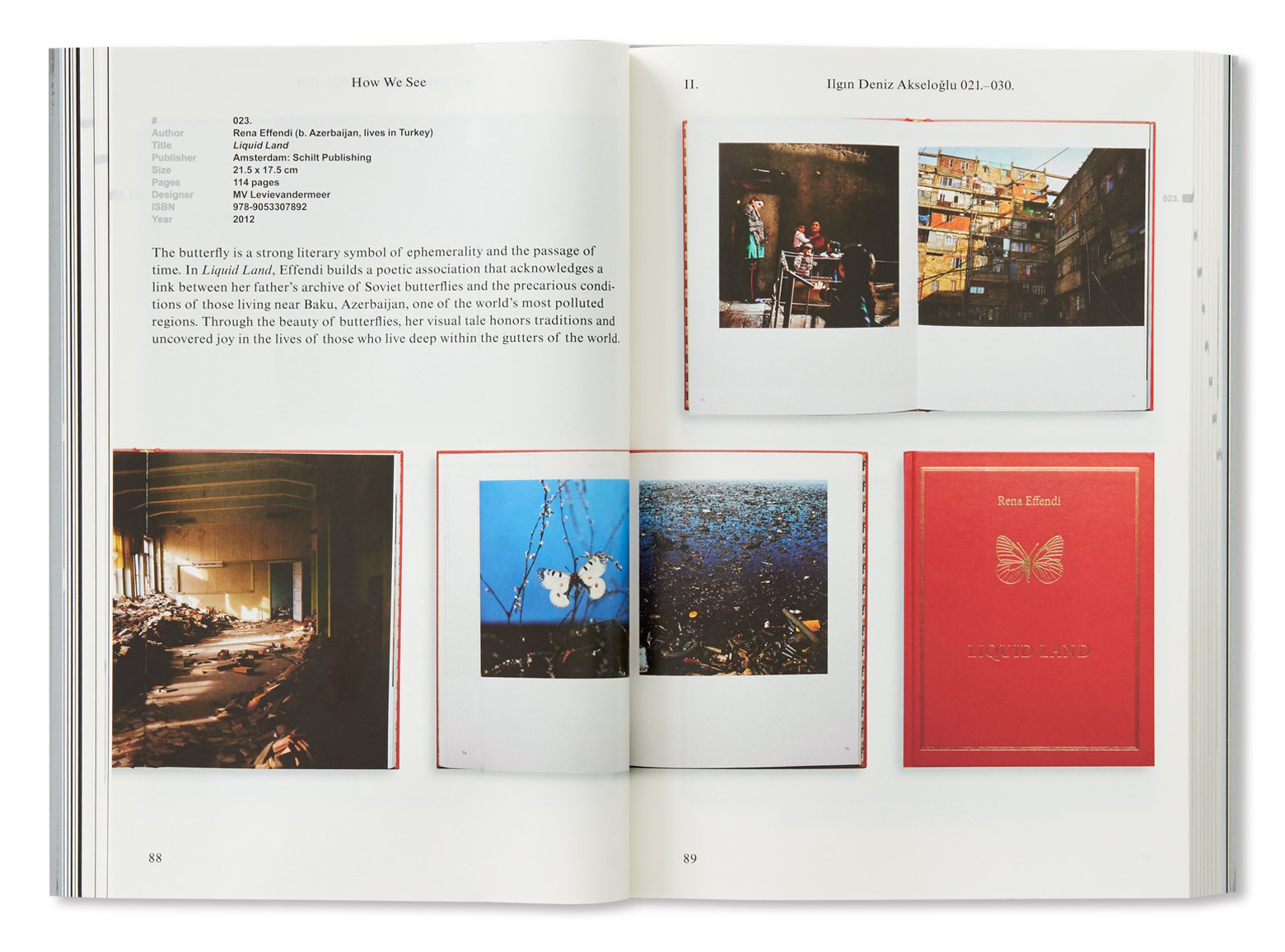

The two volumes are a response to the skewed statistics that do not account for the vast number of photobooks made by women, including several celebrated ones. For How We See, 10×10 worked with ten women photobook selectors from ten diverse geographic regions (the logic behind the publisher’s name) to select female-authored photobooks published between 2000 and 2018. In the introductory notes, each selector describes her reasons for choosing her favourite top ten photobooks, even as several important works remain excluded, such as those written by the selectors themselves. The motives undergirding photobooks by women are both exploratory and reparative, responding to social stereotypes attached to femininity, and their exclusion and lack of cultural dominance. An emergent polyvocality is reflected in the diversity of photobook formats, materials and visual languages explored in these one hundred featured texts.

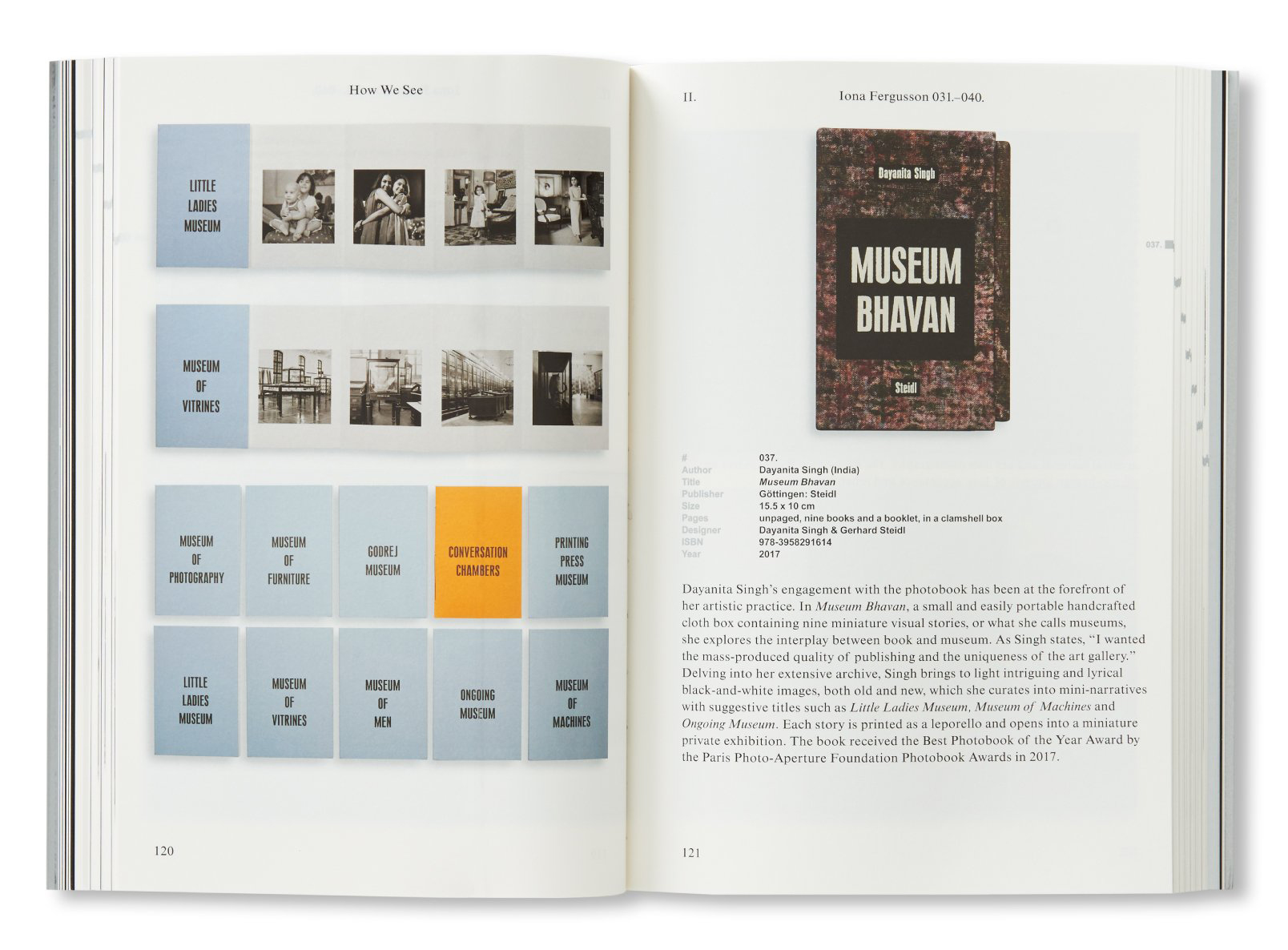

Recurrent visual themes of the body and sexuality in a masculinized world and concerns around home and family alongside feminist self-assertion index the woman-authored photobook as an intimate document, often crafted by hand, self-published in small editions, and circulated in limited networks of readership. There are also deviations from expected narratives, with musings on natural and material surroundings, a play with technologies of print and book design, and unusual uses of text. The formal quality of the photobook resonates with other personal narratives enabled by photography; such as the family album, the contact sheet and the Instagram reel, invoking a comment by Dayanita Singh, one of the featured photobook makers: ‘I just never saw/experienced photography as single images… the museums grew out of the contact sheets, as did Sent a Letter.’[4]

How We See consciously dwells on the production process for each photobook, its logic and compulsions, noting how the camera first enters the author’s world – often through the family – and the labour that goes into formulating the book(s) in singular and collaborative ways. For South Asia, Iona Fergusson, independent curator, producer and creative director, chose Gauri Gill for Balika Mela, Uzma Mohsin for Life Is for Lovers / Remains of a Revolution / Hollow, Ketaki Sheth for Twinspotting: Photographs of Patel Twins in Britain and India, Dayanita Singh for Museum Bhavan, Avani Tanya for The Snapped Rope & Other Stories from the New Bangalore and Sooni Taraporevala for Parsis: The Zoroastrians of India.[5] Viewing the photobook as a complex artefact, How We See foregrounds the sensory experience of the book- as-material-form as crucial to the process of receiving images. For instance, Homai Vyarawalla and Singh regard the camera as a prosthetic device, an extension of the eye, the arm, or the ‘third breast’, bringing the bodily sensorium into ‘birthing’ images, as the latter says.[6] Thus, the photobook draws the viewer/reader into the phenomenology of perception itself.

The six selected Indian authors and their work are globally known, hence their inclusion in the book is not surprising. Beyond presenting renowned practitioners, How We See is an invitation to engage with the work of those who have preempted and expanded the idea of the photobook. A recently concluded exhibition of photographic works by the twin photographer sisters Debalina Mazumder and Manobina Roy provided one such opportunity.[7] Their oeuvre includes a co-produced album, titled Lina Bina (c. 1930s) after their names. Such a document is hard to define as a family album. It exceeds the interior reference of kinship to include suggestions of worldly exploration and photographic experimentation by the two amateur photographers. Although Lina Bina was not reproduced for sale, an essential feature of the photobooks selected for How We See; it indicates the need for more women from this part of the world to reveal their authorship of photobooks, documents that have so far been considered too private or singular. Manobina and Debalina’s reflections on post-war Indian society, their own privileged social stratum, family and domesticity, as well as the inseparability of the camera from their persons, are narratives in feminine visuality, addressing several theoretical concerns raised by the editors.

How We See includes several photobooks that focus on the depths of women’s lives where light has perhaps never been cast, anatomically or sociologically. The works of Barbara Kasten (139), Susan Meiselas (140), Chin Chin Wu (196) and Collier Schorr (144)[8] appear under different geographically-themed segments of the book, inscribing the common concern with feminine sexuality across the world. The concealed female body is revealed to the camera, which for once is not an invasive device as much as it is both a reflective and self-reflexive mirror. The voyeuristic gaze extracts pleasure from these images of nudes – until it encounters the work of Carmen Winant (150) and Valentina Abenavoli (228).[9] Here the naked body appears scarred and contorted in pain, challenging the pleasure-seeking gaze. Navigating these images, oscillating between libidinal joy and suffering, one is reminded of how often pleasure is elided with agony, and of how the gaze needs to unflinchingly interrogate itself with regard to what it seeks from images of women’s bodies. Further, the deliberately staged body brings into relief the forms and gestures of everyday life that are otherwise obscured from sight. Ting Cheng’s Baker Salon replaces braids and buns with baked bread, while Carrie Mae Weems’ landmark Kitchen Table Series has the protagonist enact daily feminine roles around a central domestic space.[10]

A clear intervention and renegotiation with history appears in the works of several authors, especially those choosing older family images, interleaved, collaged or juxtaposed with newer ones.[11] They cull new narratives, disrupting and repudiating the closure of memorialized trajectories, and inserting subversive female voices so often customarily silenced within the reified structures of patriarchal kinship. In this rearrangement of meaning-making, images disturb and interrogate the hegemonies of linear time. These photobooks articulate a reconfiguration of all that constitutes the habitus of women: the body, the home, and the family, allowing a defamiliarization of the everyday for purposes of deeper inquiry.

The world beyond the immediate feminine context is also explored for articulations of a self that asserts or challenges gendered identity in its political relationship to the state, its uneven cultural location in a global context, and its varied sensitivities to the anthropocene. Conflating femininity with the ‘otherness’ of intersectional identities, several photobooks offer layered insights into marginalization on the grounds of sexuality,[12] race[13] and political power.[14] Some photobook selectors and authors entrench these differences, for instance Miwa Susuda’s assertion of a distinct ‘Eastern’ way of representation, while others blur them. Overwhelmingly, photobooks by women address femininity and its constricts in a more central manner than either feminity or masculinity and their constructs are addressed by male authors of photobooks. The crucial question then remains: how deeply can we read womanhood or female identity into photographs and photobooks by women? How do men and women make photos differently, and author different kinds of photobooks? Between these binaries lies the space for a spectrum of sexualities, ambiguities, mystery, celebration, pathos and humour, pushing the boundaries of photography to visually represent the ungraspable – not to simplify, but to invoke the complexities of the real world.

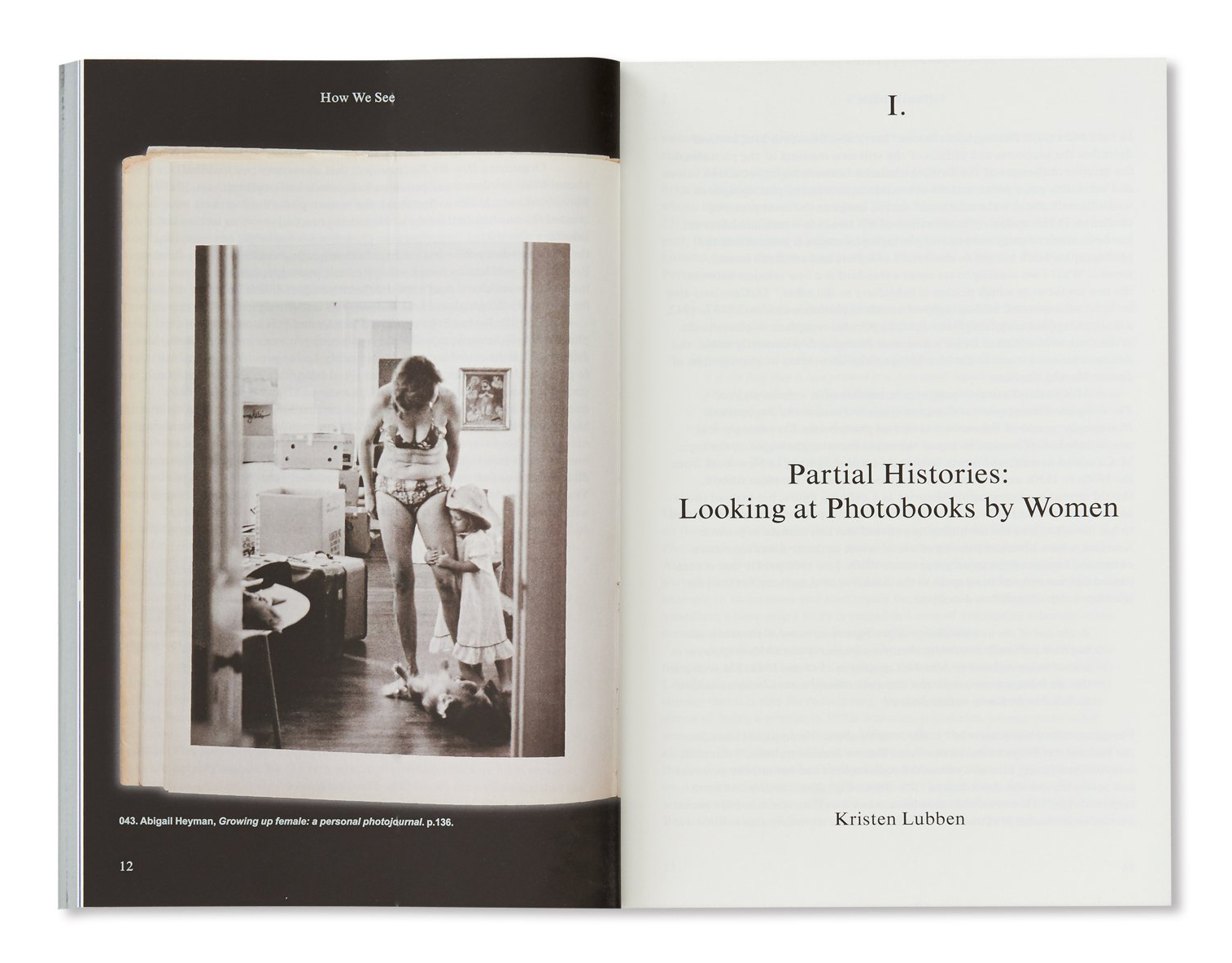

How We See is an important achievement in tracing the hitherto obscured genealogies of women’s photobooks. Women photographers and photobook makers have gone far beyond the concerns of gender in their work, even though their relegation into oblivion is mostly due to their own female identity. This volume convincingly traces the link between older practices of women informally collating photographs into albums and the later authorship of photobooks. Patrizia Di Bello’s study Women’s Albums and Photography in Victorian England: Ladies, Mothers and Flirts foregrounds a nineteenth-century feminine preoccupation with the creation and preservation of family albums, a pastime conforming to the conservative standards of Victorian society.[15] Di Bello also considers the significant practice of women making albums with photographs produced by others, cultivating a craft-intensive exercise of material engagements with textiles, collaging and accretions from everyday domesticity, enhancing the tactility of their albums; the photobooks featured in How We See echo these enhancements in the careful choice of paper, font, and dimension by their authors. Having operated outside the male-dominated and male-centric networks of photographic clubs and commercial printing, the album remains a singular, non-reproducible predecessor of the photobook. Its vocabulary carries over into the modern moment, when the creation of photobooks is facilitated by mechanical reproduction, yet their link to the ‘feminine’ Victorian album challenges photography’s predominantly masculine lineages and legacies. How We See is hence both a claim and a revelation in the worlds of photography, book publishing and art-historical critique, with the potential to catalyse numerous future inquiries.

Notes

- Teju Cole, “In Praise of the Photobook”, MACK; https://www.mackbooks.us/blogs/news/in-praise-of-the-photobook-by-teju-cole.

- Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (Paris: Farrar, Straus & Giroux Inc., 1999), p. 9.

- Naomi Rosenblum, A History of Women Photographers (New York: Abbeville Press, 1994) and Lucy Lebart and Marie Robert (eds.), A World History of Women Photographers (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2020).

- Dayanita Singh, Sent a Letter (Gottingen: Steidl, 2008).

- Gauri Gill, Balika Mela (Zurich: Edition Patrick Frey, 2012); Uzma Mohsin, Life Is for Lovers / Remains of a Revolution / Hollow (New Delhi: self-published, 2015-2016); Ketaki Sheth, Twinspotting: Photographs of Patel Twins in Britain and India (Stockport, UK: Dewi Lewis, 1999); Dayanita Singh, Museum Bhavan (Gottingen: Steidl, 2017); Avani Tanya, The Snapped Rope & Other Stories from the New Bangalore (Bangalore: self-published, 2012); Sooni Taraporevala, Parsis: The Zoroastrians of India (Woodstock, New York & London: Overlook Duckworth, 2004).

- Dayanita Singh, “Birthing the Photobook: A Matrilineal History”, Talk at Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis (9 December 2021); https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PysGvw2wCzk&ab_channel=MinneapolisInstituteofArt

- Twin Sisters with Cameras: An Exhibition of the Works of Debalina Mazumder and Manobina Roy, curated by Sabeena Gadihoke, Tapati Guha-Thakurta and Mallika Leuzinger, Jadunath Bhavan Museum and Resource Centre, Kolkata, February 2022.

- Barbara Kasten, The Diazotypes (Chicago: Graham Foundation & New York: D.A.P., 2015); Susan Meiselas, Carnival Strippers (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art & Gottingen: Steidl, 2003); Chin Chin Wu, Vis-à-Vis: Portraits of New Women (Bliesdorf, Germany: Edition Galerie Vevais, 2011) and Collier Schorr, 8 Women (London: MACK, 2014).

- Valentina Abenavoli, Anaesthesia (London: Akina Books, 2016) and Carmen Winant, My Birth (London: SPBH Editions & Ithaca: ITI Press, 2018).

- Ting Cheng, Baker Salon (Taipei: dip editions, 2016); Carrie Mae Weems, Kitchen Table Series (Bologna: Damiani & Matsumoto Editions, 2016); also see Cindy Sherman, A Play of Selves (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2007).

- Ana Paula Estrada, Memorandum (Brisbane: self-published, 2016); Eva Saukane, Roots (Stockholm: Kult Books, 2017).

- Alessandra Spranzi, La donna barbuta (Milan: Galleria Emi Fontana, 2000); Catherine Opie, Catherine Opie (London: The Photographers’ Gallery, 2000); Zanele Muholi, Faces and Phases 2006-14 (Gottingen: Steidl and New Ulm & New York: The Walther Collection, 2014).

- Liz Johnson Artur, Liz Johnson Artur (Berlin: Birke, 2016); Joana Choumali, Haabre: The Last Generation (Johannesburg: Fourthwall Books, 2016).

- Laura El-Tantawy, In the Shadow of the Pyramids (Cairo: self-published, 2015).

- Patrizia Di Bello, “Introduction”, Women’s Albums and Photography in Victorian England: Ladies, Mothers and Flirts (New York: Routledge, 2007), pp. 5-14.

Suryanandini Narain is Assistant Professor of Visual Studies at the School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. She has written extensively on photography in India, especially around themes of women, the family, the home and studio photography, in Marg, Art India, Visual Anthropology Review, Trans Asia Photography Review and other arts journals. She co-edited Framing Portraits, Binding Albums: Family Photographs in India (Zubaan, forthcoming 2023). She teaches courses on Indian visual culture, photography, aesthetic theory and critical writing, and supervises research students working on photography, graphic novels, digital visual cultures and popular art. Her next project is a monograph on domestic visual culture as shaped by middle-class women in India.

Suryanandini Narain is Assistant Professor of Visual Studies at the School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. She has written extensively on photography in India, especially around themes of women, the family, the home and studio photography, in Marg, Art India, Visual Anthropology Review, Trans Asia Photography Review and other arts journals. She co-edited Framing Portraits, Binding Albums: Family Photographs in India (Zubaan, forthcoming 2023). She teaches courses on Indian visual culture, photography, aesthetic theory and critical writing, and supervises research students working on photography, graphic novels, digital visual cultures and popular art. Her next project is a monograph on domestic visual culture as shaped by middle-class women in India.