By Ruxmini Choudhury

I first learned about Anne de Henning [Fig. 1] during the lockdown of 2020 from Mr. Rajeeb Samdani, co-founder and trustee of the Dhaka-based Samdani Art Foundation. At that time, the Foundation was trying to find photographs of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the founding father of Bangladesh. As I looked through de Henning’s website, I stumbled upon a black-and-white photograph of Sheikh Mujib that I had never encountered before. [1]

When I saw this portrait of Sheikh Mujib, the obvious question that came to my mind was, ‘Why did Anne de Henning photograph him and what brought her here to Bangladesh in 1972?’ In order to find answers, I contacted de Henning and learned about her incursion into the newly declared independent Bangladesh in April 1971. With three fellow journalists, Anne de Henning broke the two-week news blackout in the early days of the conflict. She then returned in 1972 to photograph the political leader Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, who fought to decolonize the nation only to be assassinated three years after its Independence. It took us a year and a half of back-and-forth conversations to organize de Henning’s exhibition Witnessing History in the Making, which was held in Dhaka in December 2021. I curated the exhibition under the aegis of the Samdani Art Foundation in partnership with the Centre for Research and Information, Dhaka. As she had held on to the negatives for fifty years, this was the first time de Henning’s rare images of those traumatic months were displayed. [2] The second iteration of the exhibition took place in Paris at the Guimet National Museum of Asian Arts. [3] In the exhibition, I focused on the black-and-white photographs Anne had taken of the war. These photographs are so different from those I have encountered so far in the representation of Bangladesh’s Liberation War. They are simple yet powerful statements. Later, Anne said, ‘My photographs were taken over a short period in the early stages of the conflict. I was not seeking a particular narrative. They do not deal with the atrocities perpetrated against the Bengali population, which were horrendous. That was beyond the realm of what I witnessed. What they show is the courage and determination of the Bengali people, whether fighters or civilians.’[4]

In December 2022, we welcomed Anne de Henning back to Bangladesh after fifty years. During our conversations, I asked what made her decide to be a photographer. Anne answered, ‘In my youth, what I found most compelling about photography was its capacity to convey dramatic events happening across the world. This is how I developed an early interest in photography. When I was growing up, there was no television at home. One could discover the world further afield by reading books and magazines. I still have tear sheets from Paris Match and LIFE magazine, with their extensive colour features on world sites and black-and-white coverage of major political events. I remember distinctly a double spread of a large gathering of Soviet apparatchiks watching from the Kremlin as a mammoth parade filed past on the Red Square to celebrate the anniversary of the October Revolution. I also remember more dramatic images of the brutal Soviet repression of the Hungarian Uprising in 1956, taken by a French photographer who was killed while photographing the event.’ [5]

In late March 1971, Anne was photographing in Nepal when she heard that war had erupted in East Pakistan. She immediately decided to fly to Calcutta (present day Kolkata). Following the victory of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s Awami League in the December 1970 elections, she could sense history was in the making. Anne did not want to miss the foreseeable birth of a new nation.

At that time, Pakistani authorities in Dhaka were not allowing foreign journalists to enter the country. They did not want anyone to report on the atrocities perpetrated by the authorities on civilians through ‘Operation Searchlight’, which had been launched on 26 March 1971.

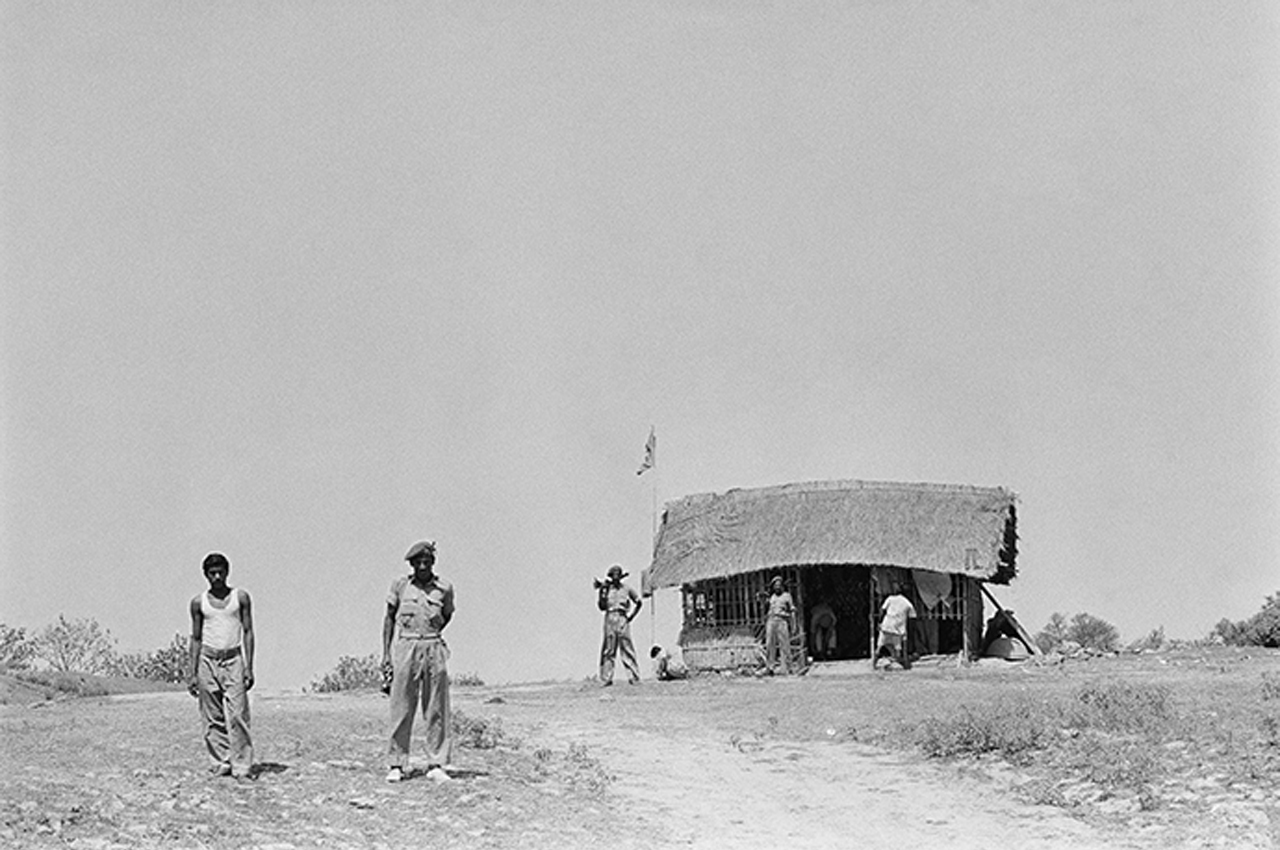

After two failed attempts to cross the border on her own at Jessore, Anne teamed up with Associated Press (AP) photographer Michel Laurent, AP correspondent Dennis Neeld and Columbia Broadcasting Services (CBS) correspondent Patrick Forest. Though she had never met them before, they seemed as determined as she was to break the news blackout. This intrepid group hired a beaten-up Ambassador car and loaded it with three jerrycans of petrol. They drove up north, where, at Darshana, they finally managed to cross the border. Anne recalled her first encounter with the newly-declared independent Bangladesh[6], ‘The first striking memory I have of my crossing to East Pakistan from India in the blistering heat and dead silence of an early April day in 1971 is of a handful of young Mukti Bahini (Liberation Army) stepping out of their makeshift observation post flanked by a tall bamboo pole flying the green, red and yellow Bangladesh flag. They were dressed in khaki trousers and worn-out shirts. Their armament consisted of old 303 Lee Enfield rifles [Fig. 2]. They greeted us by saying, with a broad smile, “You are now in free Bangladesh!”’[7]

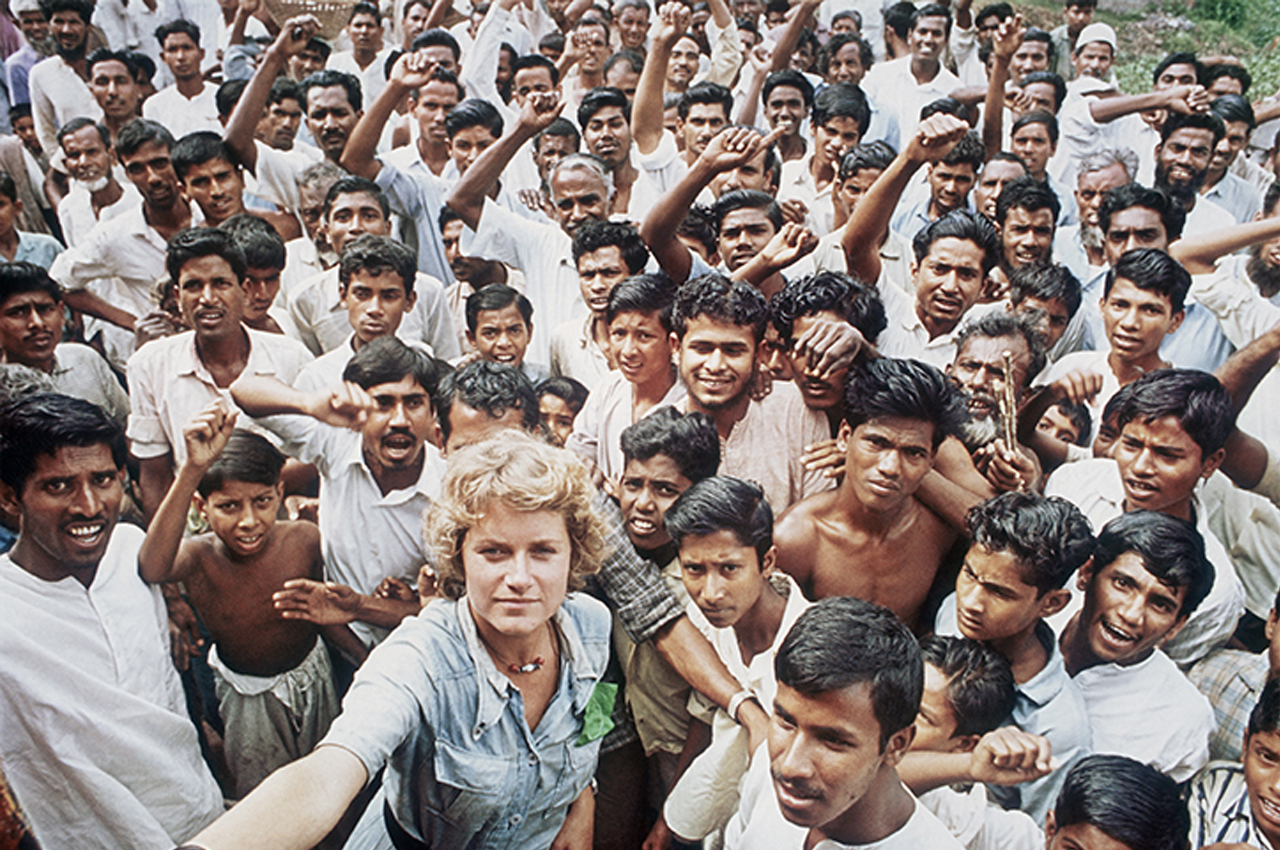

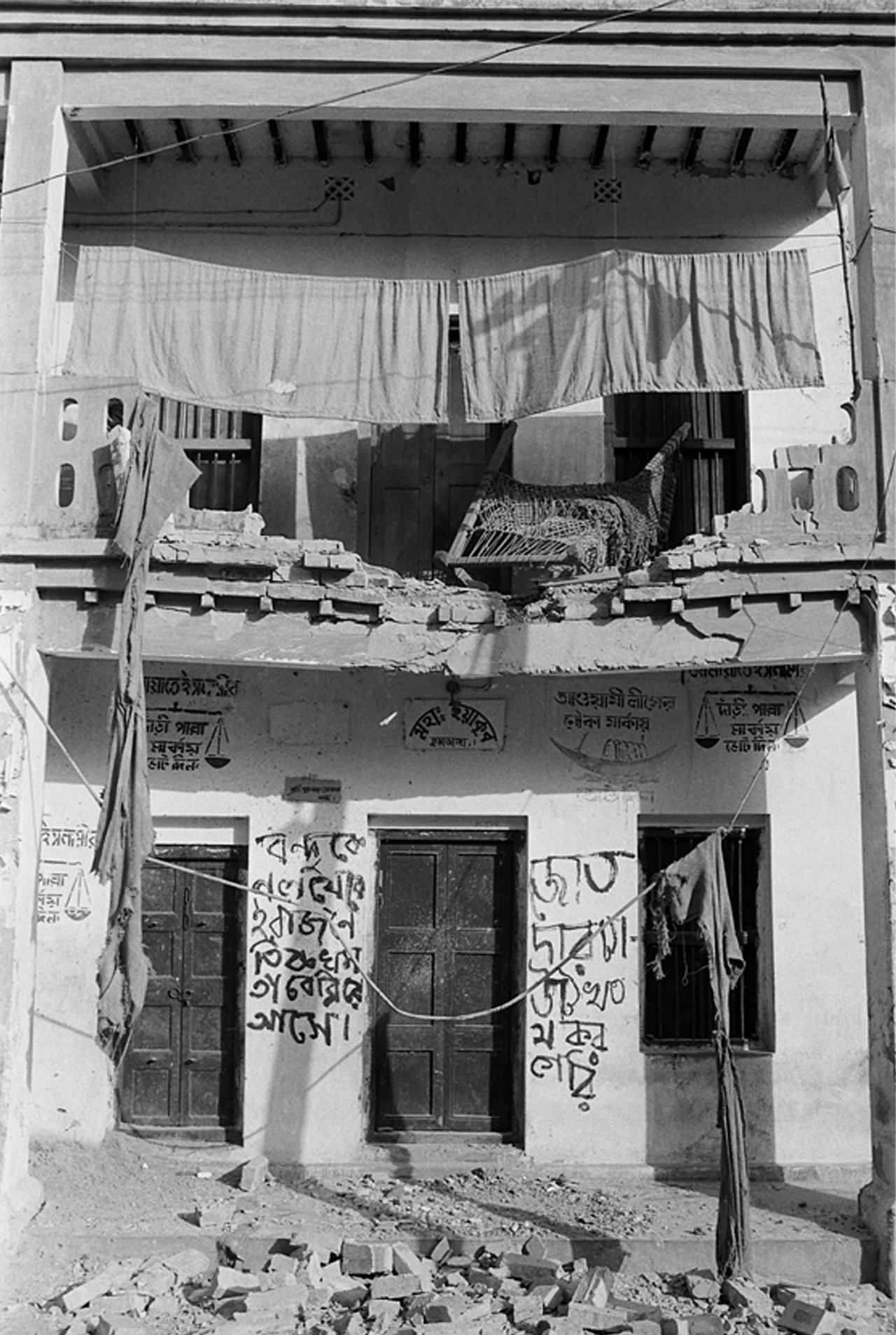

In Kushtia [Fig. 3] and Pangsha, large crowds of young men driven by enthusiasm chanted loudly ‘Joy Bangla’ (‘Victory to Bengal!’) [Fig. 4]. Anne said the slogan echoed the hope and determination of the Bengalis for a country of their own. They asked Anne and her colleagues to tell the world about their plight and dire need for modern military equipment. It was at the early stage of the liberation war when Bengalis were keen to fight but hardly had any weapons to fight with. In Pangsha, Anne was struck by a group of freedom fighters, including young boys, demonstrating their readiness to fight with bows and arrows.

In Kumarkali, she encountered hundreds of refugees, especially women and children. Fleeing on foot, by horse carts, or trying to board refugee trains, they sought to escape bombardment and massacre by the advancing Pakistani military [Fig. 5]. Eventually, ten million refugees would cross into India.

After four days of travelling by truck, boat and train, the group reached Goalundo Ghat, a small river port. Armed with films and articles by the other three – who had decided to move deeper into the country – Anne decided to return to Calcutta to get news of the situation out as quickly as possible. She shared, ‘By then, the situation had taken an ominous turn. In the middle of the night, Pakistani gunboats coming down the Padma River from Chittagong were about to cross the river at Aricha and attack our side. In Rajbari, there was great confusion and a lot of shooting between freedom fighters and a high number of defectors to the Pakistani army. Just outside the small outpost where I had taken shelter, a loud commotion erupted when the Mukti Bahini started fighting for the few available rifles.’ [8]

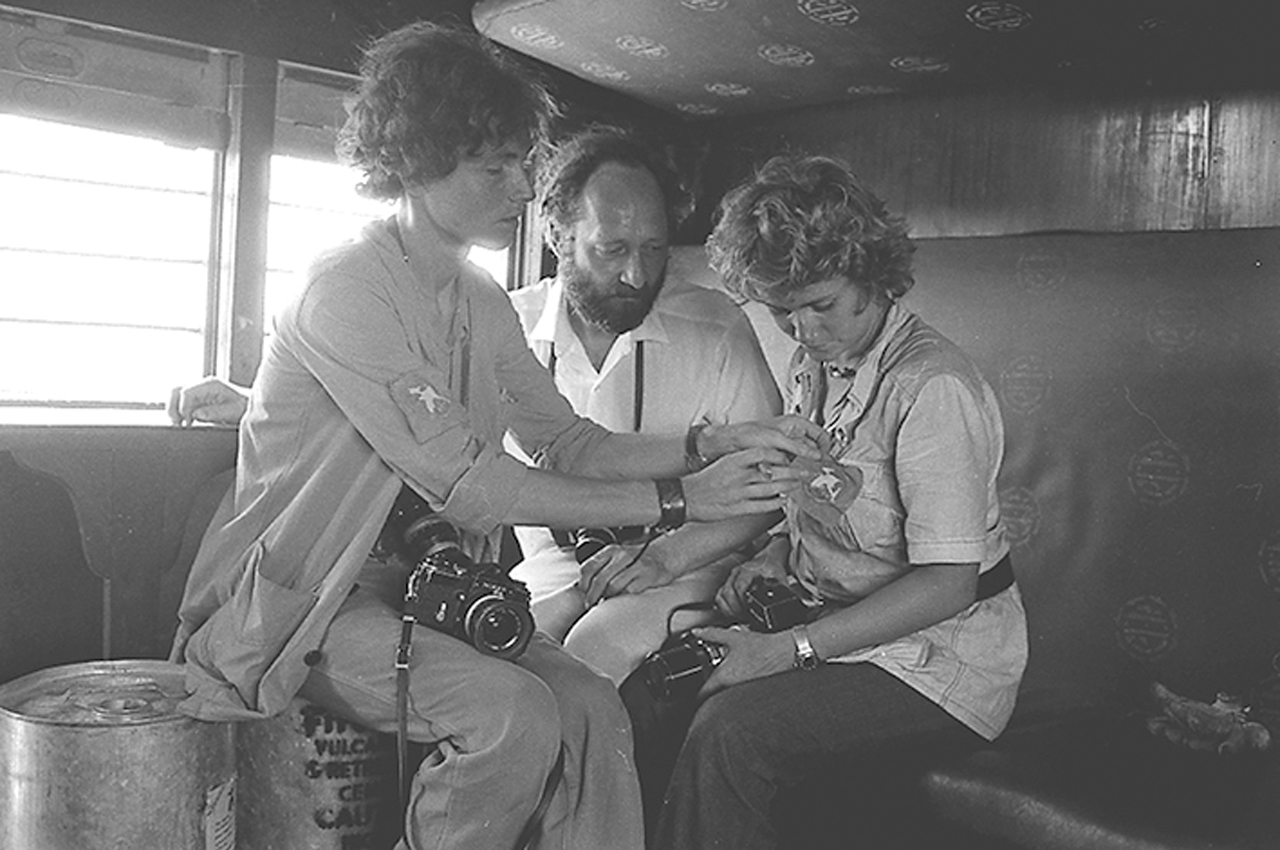

From here, she was taken to the station under crossfire to board an overcrowded refugee train bound for Calcutta. Anne said that when she stepped into the hotel covered in dust and wearing a small Bangladesh flag pinned to her shirt [Fig. 6], it was obvious that she had been to the war zone while other members of the press were still trying to get in! [9]

When I asked her what it had been like to be a woman photographer in those days, Anne said, ‘Except for the danger inherent to a war situation, at no point did I feel threatened as a woman. In Bangladesh, the freedom fighters, local authorities and civilians were all keen on helping me do my work in order to get the news out. In a broader context, when I began moving into the professional milieu of journalists and photographers in 1969, when I was in my early 20s, it felt like a competitive environment, but I also met supportive peers. I was able to team up with fellow members of the press when needed in Vietnam and Bangladesh. However, in most cases, I have always made it a point to travel and work on my own. For that reason, being a woman was both an advantage and a disadvantage. I would rather discuss the advantages. Being a woman sometimes allows me to gain access more easily. People can also be less wary of women. For example, when I set out to photograph difficult-to-access hill tribes in the Golden Triangle in Laos and Thailand or the Dayaks up river in the Borneo jungle, I had to go into restricted areas due to local insurgencies. When I got caught by the military authorities, I was simply turned back. I would then find another way to reach my goal. Had I been a man loaded with heavy photographic equipment, such as mine, I would have probably gotten into worse trouble.’

Anne returned to Bangladesh on 7 April 1972, just a year after penetrating the war zone. This time, she was driven by a strong desire to see and photograph Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, then Prime Minister of Bangladesh. Sheikh Mujib was seen as the man who had led the entire nation to freedom, who had been imprisoned in Pakistan so far from his homeland, and yet had kept his people inspired to fight for their freedom. When she was in Calcutta, she heard that Sheikh Mujibur Rahman would be giving a major speech in Dhaka. [10] Anne said the powerful charisma of Sheikh Mujib and the vividly striped shamiana (canopy) created such a vibrant atmosphere that she chose to shoot in colour rather than in black and white [Fig. 7].

On Anne de Henning’s last visit to Dhaka in December 2022, people kept asking her if she had the chance to talk to Sheikh Mujib. In response to these queries, she had such a simple answer, ‘The victory of Bangladesh over the Pakistan Armed Forces, with the help of the Indian Armed Forces, would not have been possible without the long and ongoing commitment of the independence movement led by Sheikh Mujib. I was not there for a political agenda or a story for the press. I was there simply to photograph the man I had heard so much about.’

In this manner, Anne de Henning captured a crucial moment in Bangladesh’s history. Rediscovering her photographs, at the time when the country turned fifty years old, has been a blessing to us. Many of us grew up listening to the memories of the war from our parents and grandparents – but rarely with photographs to match them. Anne’s photographs remind me of the stories I heard from my grandfather, who was a police officer at that time. Along with his colleagues, he gave away old rifles that were in storage to the freedom fighters. Or my mother’s story, in which she and other friends would sew small flags of the new nation from their old clothes and run around their alley proudly. The press was more interested in looking at images of devastation and helplessness than smaller victories. Perhaps that is why Anne de Henning’s poignant and humane photographs did not surface for so many decades.

Notes

- Anne de Henning’s website: http://www.annedehenning.com/portraits/.

- When I expressed my surprise at not having discovered her photographs earlier, Anne said: ‘In April 1971, I sent my films from Calcutta to Paris to the Gamma photo agency. (…) In those days, after being published in daily newspapers and weekly magazines, news photographs disappeared quickly into archives. For a long time to come, there would be no internet to spread the news widely and instantly, and no image banks to consult or purchase such photographs online. What I realized when these images were recently rediscovered is that news coverage has a very short lifespan. It vanishes very quickly out of sight, but it takes many years to turn into history and be rediscovered as such.’

- Philip Bruno, “Au Musée Guimet, à Paris, Anne de Henning ou les tribulations d’une photographe en Asie”, Le Monde (November 5 2022), https://www.lemonde.fr/culture/article/2022/11/05/au-musee-guimet-a-paris-anne-de-henning-ou-les-tribulations-d-une-photographe-en-asie_6148655_3246.html.

- Rebecca Suhrawardi, “This Month At Paris+ Par Art Basel, Bangladeshi Art Took Center Stage”, Forbes (3 November 2022), https://www.forbes.com/sites/rebeccasuhrawardi/2022/11/03/this-month-during-paris-par-art-basel-bangladeshi-art-took-center-stage/?sh=2160e6a9155f.

- Pateman, “Documentary Photographer Anne de Henning discusses previously unseen photos from the Bangladesh Liberation War”, Alamy (25 January 2023), https://www.alamy.com/blog/documentary-photographer-anne-de-henning-discusses-previously-unseen-photos-from-the-bangladesh-liberation-war.

- Bangladesh had been created on 26 March 1971, after secession from Pakistan.

- Anne de Henning, “Freedom in the making: Bangladesh by Anne de Henning – in pictures”, The Guardian (10 December 2021), https://www.theguardian.com/world/gallery/2021/dec/10/freedom-in-the-making-bangladesh-by-anne-de-henning-in-pictures.

- Email sent by Anne de Henning on 23 October 2021.

- Interview taken on 18 December 2022, at the Thai Emerald Restaurant, Dhaka.

- Later, I found out from old archives that this was the first Council Meeting of Awami League of independent Bangladesh.

Ruxmini Choudhury is a curator, art writer, researcher, and bilingual translator based in Dhaka, Bangladesh. She has been working at the Samdani Art Foundation since 2014. Among the many initiatives she has introduced and developed for the Samdani Art Foundation are its art mediation programme and the Samdani Artist Led Initiatives Forum, which are part of her ongoing interest in exploring ways to make art more approachable and interactive for the public. Her research has supported the growth of curatorial knowledge about Bangladesh through her collaborations assisting many international curators on shows in Dhaka, such as the Dhaka Art Summit, as well as in Hong Kong, India, Austria, Norway, Dubai, among others.

Ruxmini Choudhury is a curator, art writer, researcher, and bilingual translator based in Dhaka, Bangladesh. She has been working at the Samdani Art Foundation since 2014. Among the many initiatives she has introduced and developed for the Samdani Art Foundation are its art mediation programme and the Samdani Artist Led Initiatives Forum, which are part of her ongoing interest in exploring ways to make art more approachable and interactive for the public. Her research has supported the growth of curatorial knowledge about Bangladesh through her collaborations assisting many international curators on shows in Dhaka, such as the Dhaka Art Summit, as well as in Hong Kong, India, Austria, Norway, Dubai, among others.