By Suryanandini Narain

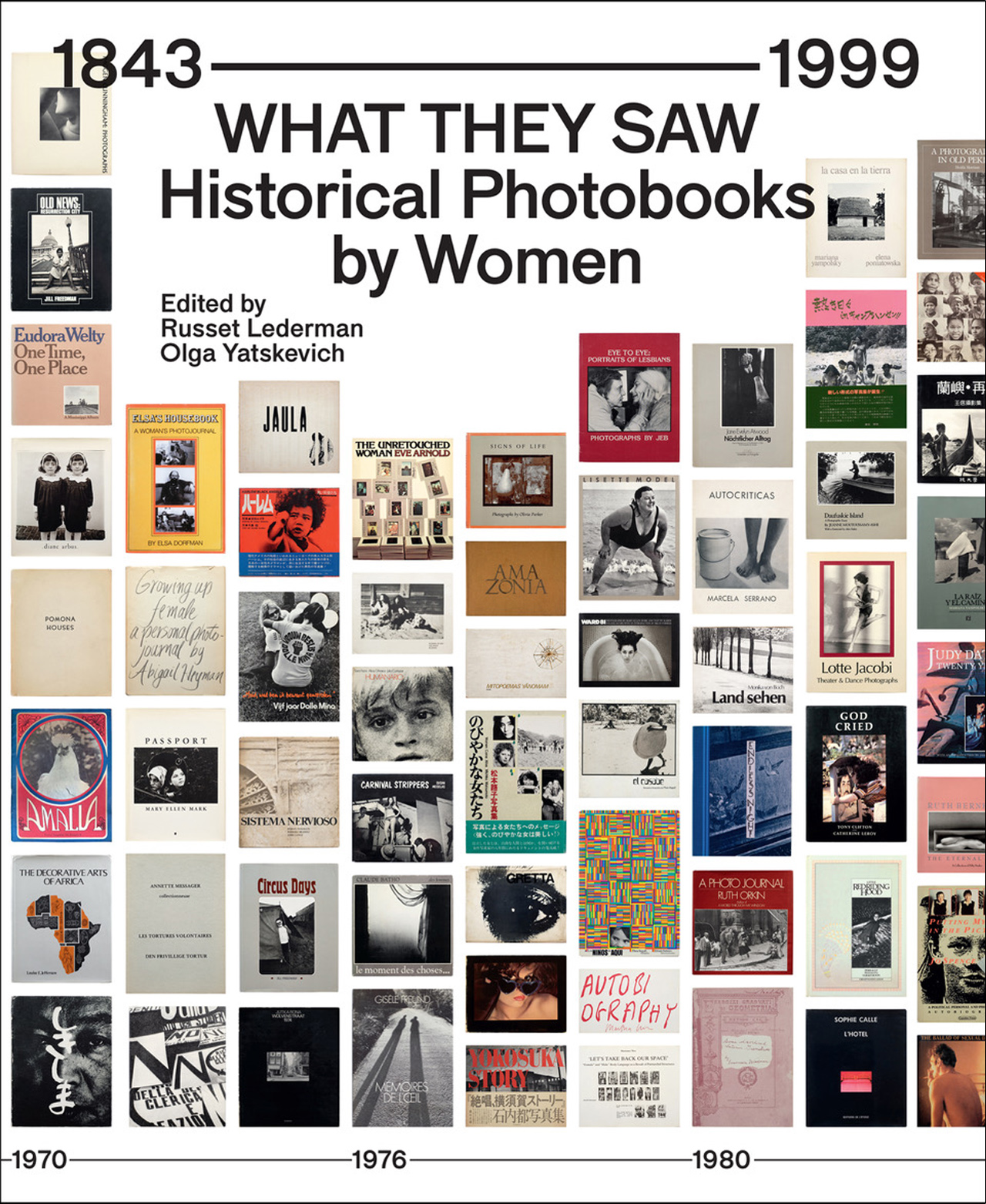

How We See: Photobooks by Women (2018) was followed by a sister publication in 2021, titled What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843–1999, also produced by 10×10 Photobooks. Its main objective was not to rewrite the history of photobooks that had excluded women authors since the inception of the camera but to ‘unwrite’ a history that was ‘overly subjective, inaccurate and riddled with omissions’ (4). In a larger format compared to the previous volume, What They Saw is a restitution of the long, often-forgotten and deep history of feminine engagement with the photobook from 1843–1999. This was heralded by Anna Atkins, whose work predated that of Henry Fox Talbot in the creation of cyanotypes of the natural world.[1] Several historically conventional parameters could not predict the success of a woman photobook-maker. While women of means such as Anna Atkins and Julia Margaret Cameron have become well known for their works, others such as Louise Laffon and Isabel Agnes Cowper have not been granted the same kind of recognition, despite occupying official positions in their countries.[2] Their careers were taken on from the men in their families, from whom they received training as well as whose camera equipment they wielded in their photographic businesses.

The key contribution of the second volume is a redefinition of the photobook itself. By including albums, maquettes, zines, exhibition pamphlets, scrapbooks and artists’ books, the term essentially incorporates all works ‘assembled (as) a “book” composed of photographs’ taken by the authors themselves or by others (5). An additional element is a parallel timeline of other photobooks as well as important books, novels, magazines and historical events in the decades under discussion, marking time to give a wider context. As a retrospective companion to the previous publication, What They Saw is an open invitation to the world to complete what it commences. It rewrites photobook history through further exploration of hitherto undiscovered and overlooked work in the field by women to ‘redetermine the importance we place on history as we think we know it’ (8).

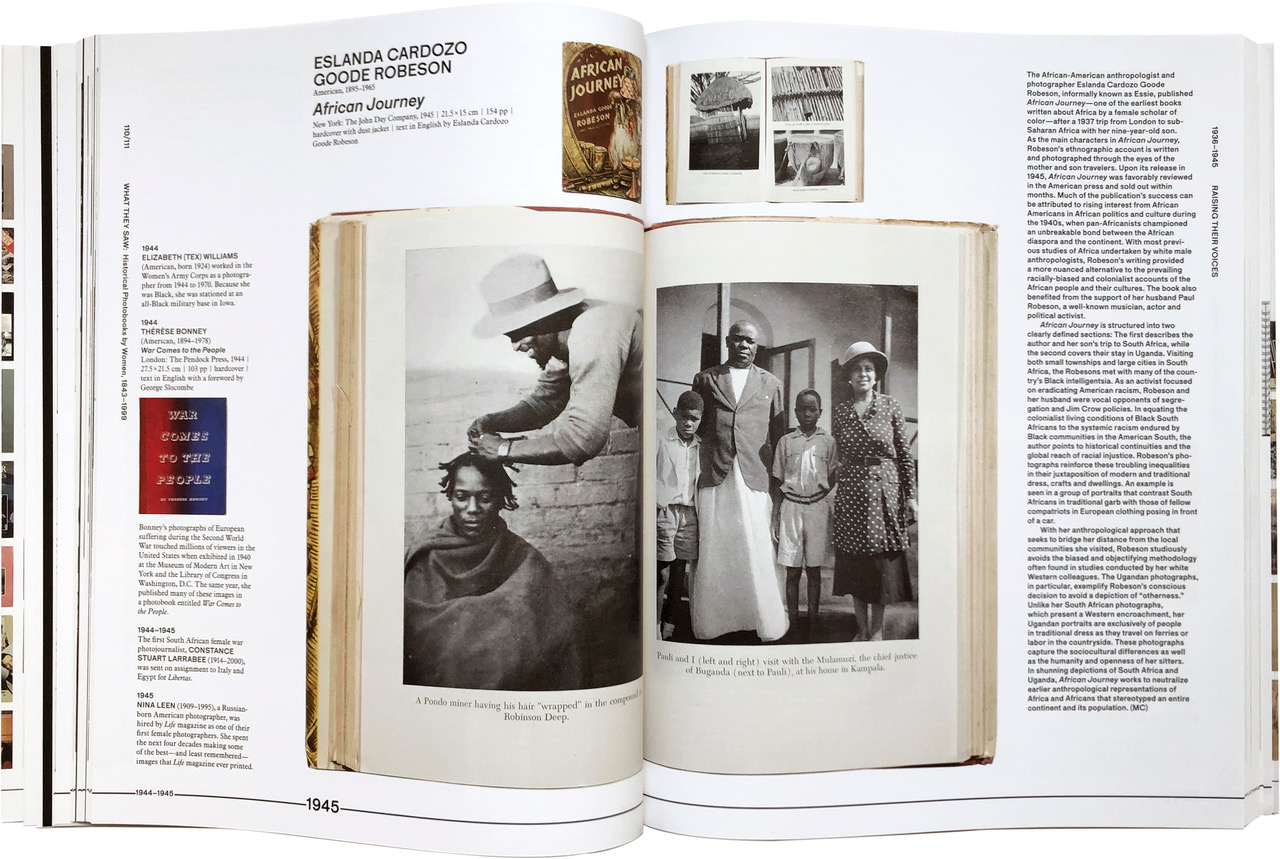

Echoing the differences that gender brings to their work, female photobook authors reveal a unique sensitivity to intersectional identities taking shape in colonial contexts. Alice Seeley Harris’s documentation[3] of the atrocities of Belgian colonial rule on the Congolese in the early twentieth century contributed to the larger effort towards gaining freedom for Congo. Her work was followed by several photobooks on both sides of the argument, including some supportive of social differentiation, such as Hedda Walther’s sympathies for Nazi conservatism towards women and Erna Lendvai-Dircksen’s invocation of a pure German national identity, segueing into eugenics.[4] Other works were more mainstream ethnographic studies of the non-West, such as Lotte Errell’s studies of the people of the Gold Coast, in whose defence the editors of this volume invoke her own persecuted Jewish identity. They underscore Errell’s ‘endeavour to demonstrate dignity and respect by showcasing individuals and providing details about their lives and culture’, even as her ‘text and images perpetuate a colonialist framework.’[5]

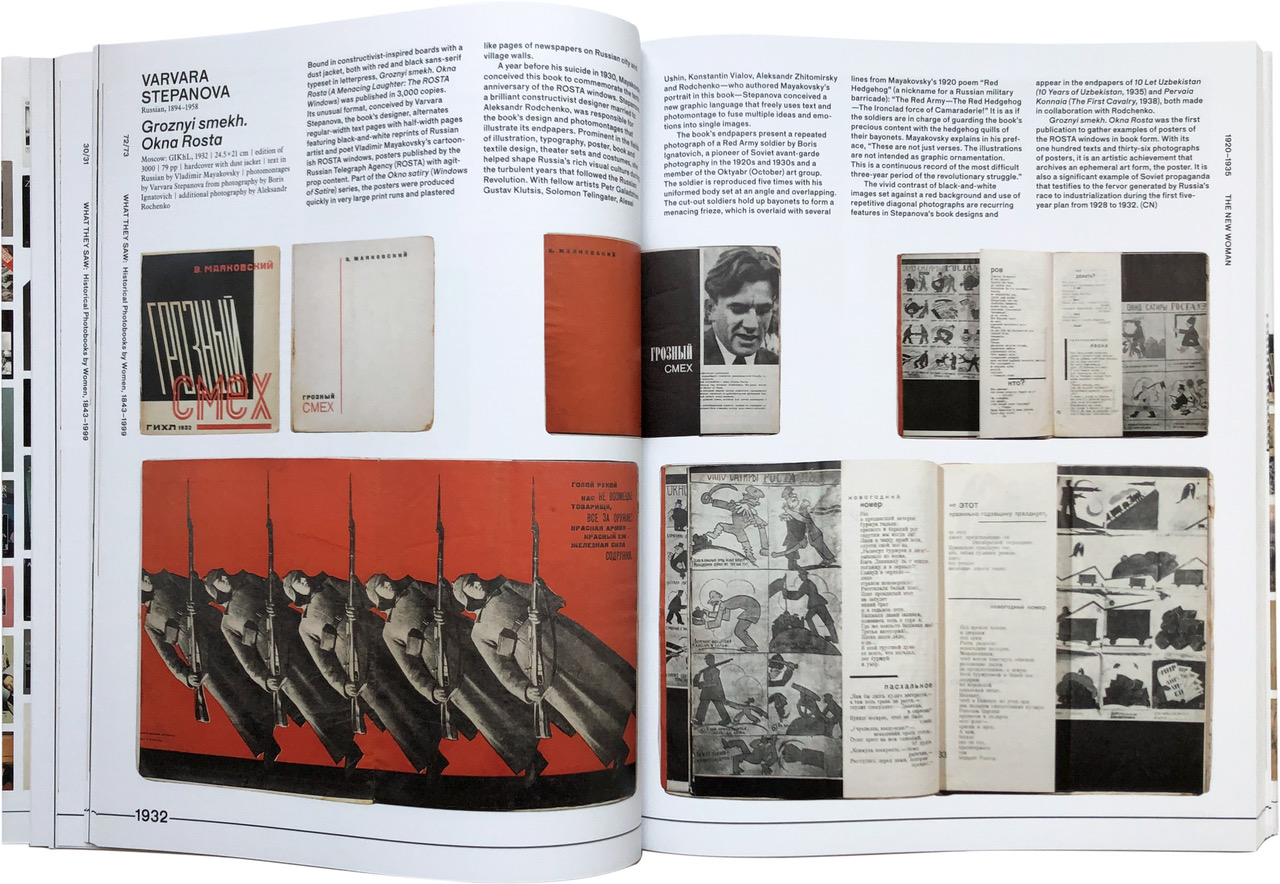

The female nude began to figure in photobooks by the “New Woman” of the first decades of the twentieth century, even as machine aesthetics became a major trope in response to rapid industrialization and Russian Constructivism. The seemingly divergent subjects of body and factory were sometimes authored by the same bookmaker, such as Germaine Krull.[6] The war years saw the emergence of women wielding the camera with greater freedom, as lens-based technology had truly democratized by then. In the persistent shadow of the Great Depression of 1929, the subject was democratized too, with childhoods,[7] labour, migration[8] and everyday urban life[9] being photographed as marked by the losses and feats of war. Photography came forth as a modern medium, experimenting with the Pictorialist tradition led by the Photo-Secessionists such as Alfred Stieglitz. This is reflected centrally in the portrayal of the body, whether as the Native American subject in Helen Post and Laura Gilpin’s works[10] or as the dancer Martha Graham in Barbara Morgan’s work.[11]

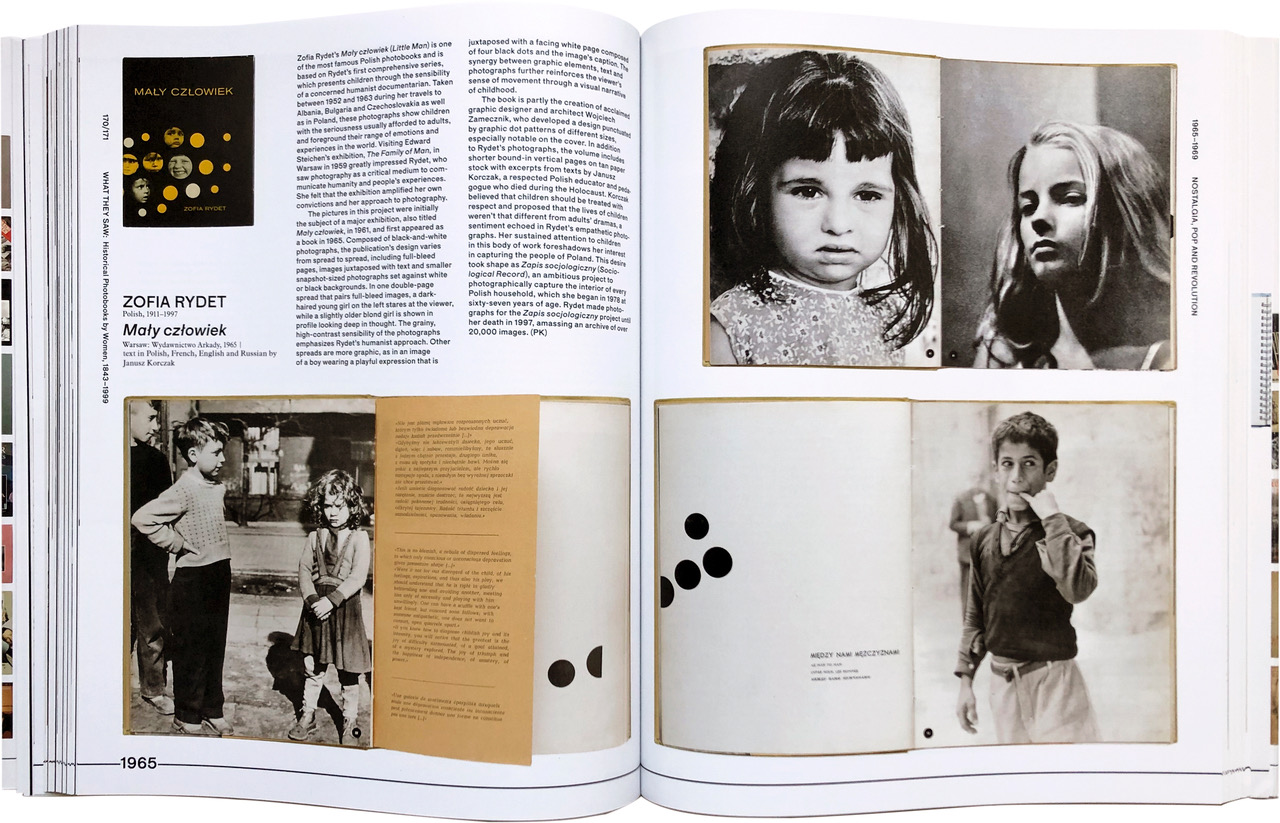

In photobooks produced in the postwar decade, some of the same themes deepened, such as childhoods that propagated hope for the future. Others moved away from the war to understand the larger human condition through a post-ethnographic, empathetic interest in other cultures. Christine Hult-Lewis, in her introduction to this section of What They Saw, credits The Family of Man exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1955 for a growing sensitivity to humanist concerns.[12] She also acknowledges the role played by professional spaces such as LIFE magazine and Magnum Photos in the creation of photobooks by their women photographers. Travel and photography became new ways of exploring other cultures, and photobooks responded to this desire to look at the ‘endurance of nature and civilizations’ (117). The postwar era also saw a resurgent feminine identity in the wake of publications such as The Second Sex (1953) by Simone de Beauvoir and The Feminine Mystique (1963) by Betty Friedan, which changed the ways in which women looked at themselves. The professionalization of women in photography saw new names come to the fore, with their work spanning quotidian, spectacular and marginalized subjects.

Japan was newly identified as a site from which women authors produced photobooks on diversely evocative subjects, ranging from an anthropological study of sex workers operating in a postwar society to artistic experiments in Abstract Expressionism.[13] Miyako Ishiuchi’s Endless Night (1981) and Mao Ishikawa’s Atsuki hibi in Kyampu Hansen (1982) persist with the theme of the Japanese sex worker in the aftermath of the Second World War, even while the Western woman photobook-maker celebrated the nude female body for its aesthetic potential.[14]

The end of the 1960s saw several important political developments, such as the Cold War, the Cuban Revolution, the construction of the Berlin Wall and political instability in Argentina and East Europe. Ironically, photobooks by women from these areas seldom addressed these developments directly. Instead, they accessed disturbances in society by tangentially focusing their lens on a vibrant counter-culture within the everyday,[15] an eternal landscape,[16] or on people in deepest despair in psychiatric institutions.[17] Retrospective inspiration from older themes and techniques influenced some authors, such as Berenice Abbott after she discovered Eugène Atget’s images from Paris in the 1920s,[18] while others heralded the use of new technology such as colour in photography.[19]

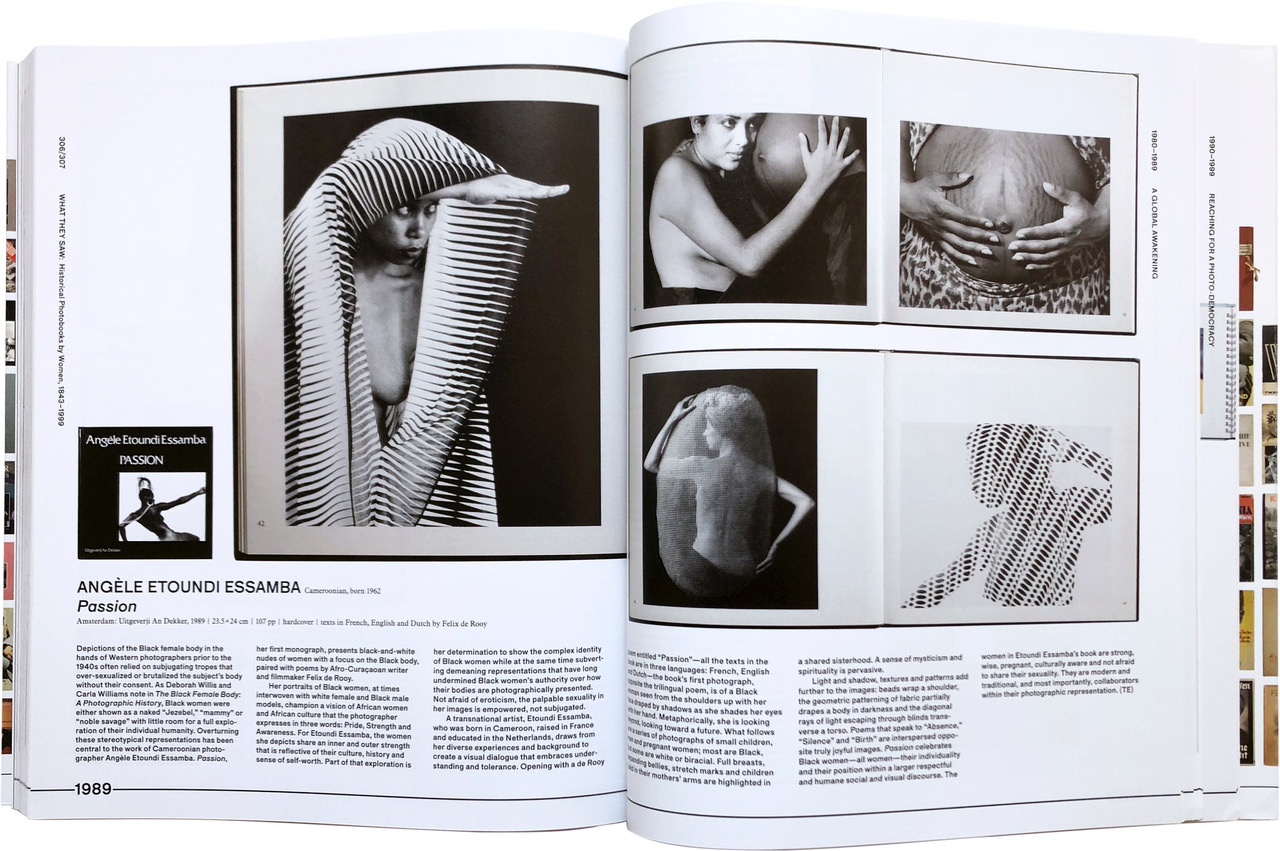

By the 1970s, the names of some women photobook-makers had become well known with established publishing houses supporting their work. This included the likes of the United States-based Imogen Cunningham, Berenice Abbott, Mary Ellen Mark and Diane Arbus. The self-published photobook still had a strong base, with the feminine gaze turning inward to look at individual or autobiographical stories addressing wider issues. While a larger concern with society’s patriarchal mores continued, the feminist metaphor for expression became highly personal and corporeal, as seen in the works of Abigail Heyman, Annette Messager and Elsa Dorfman.[20] Female sexuality grounded the photobooks being produced not only across the Euro-American world but also in Japan. As the ūman ribu (women’s liberation) movement took hold, it became the subject of Michiko Matsumoto’s photobook.[21] Miyako Ishiuchi’s landmark work in photobooks extended to women’s art practice as she brought ten women artists together in an exhibition in Tokyo in the mid-1970s.[22] Sexual politics manifested itself boldly in photobooks by Susan Meiselas on carnival strippers, while JEB (Joan E. Biren) and Martha Wilson began to explore non-binary identities.[23] This “other” sexual identity extended to looking at the racially and culturally marginalized body, such as in works by Eve Arnold, Claudia Andujar and Thea Segall. [24] These works were redemptive at a period in time that recognized photography’s own violence, its acts of objectification and exoticization, most importantly articulated by Susan Sontag in her pathbreaking text On Photography (1977).

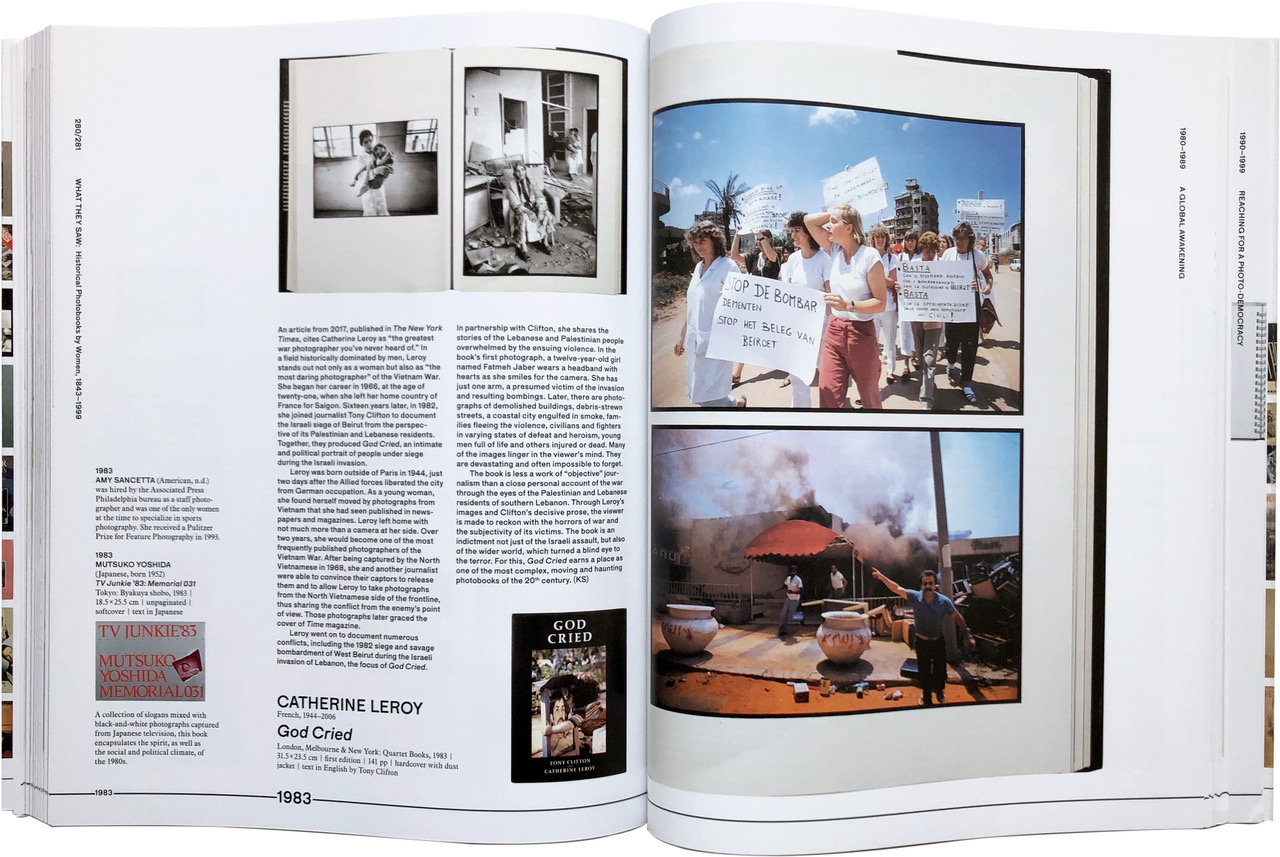

In the 1980s and 1990s, the second wave of feminism waned with the throes of global capitalism, accompanied by technological advancements like four-colour commercial offset printing and, later, the transformation of the camera into digital mode. Photography had changed forever, with strident hues defining Nan Goldin’s work or the innovative accordion format of Clarissa Sligh’s photobook being facilitated by new printing technologies. [25] Self-publishing through buyable printing machines allowed more women to produce their work by circumventing the gatekeepers of the art and book publishing scenes. Unlikely locations became the subjects of photobooks by Sophie Calle and Mary Ellen Mark, as they explored a hotel and a street corner, respectively, in their landmark works L’Hotel (1984) and Streetwise (1988). These changed the narrative for the way photographs entered print, compelling the gaze to acknowledge realities beyond the pale of the conventionally defined aesthetics of “high art”. Importantly, this section of the volume, titled “A Global Awakening”, acknowledges Dayanita Singh’s work titled Zakir Hussain: A Photo Essay (1986–87) and asks if there were no other women photobook-makers in South Asia at the time. In the light of the expanded definition of the photobook, offered by this volume, one is inclined to think that there are more works, couched as albums, scrapbooks and diaries, that are yet to surface from South Asia. Evoking the title of a 2019 conference organized by the women photographers’ collective Fast Forward, How do Women Work?, a speaker had said, ‘Women have always worked, and they will continue to do so.’[26] It is only a matter of time before their work is recognized and given its due in the history of photography.

The last segment of the book includes photobooks up until the turn of the millennium, challenging stereotypes of femininity and women’s authorship. Japanese authors Hiromix[27] and Yurie Nagashima[28] contest the derisive label of onna no ko shashin (girls’ photographs) with unusual images of their everyday lives and domestic interiors. The same defamiliarization of the everyday context appeared in the works of Tokuko Ushioda,[29] Sally Mann[30]and Tina Barney,[31] who turned the lens towards domestic spaces in the United States of America. That prejudices against gender and race continue to persist in our society, even several decades after powerful social movements to address them have taken place, is illustrated in the works of Carrie Mae Weems and Ruiko Yoshida.[32] As a final leap in form, photobooks engaging directly with text such as those by Shirin Neshat[33] and Barbara Kruger[34] herald a new relationship between photography and words, a fraught yet evolving terrain of representation.

How We See and What They Saw are extensions of Linda Nochlin’s central and very direct inquiry into Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?[35] They dive deeper into the lives of women, several of whom were perhaps not granted the identity, education and institutional status of being artists, nor was their work called “art”, at least in their lifetimes. Such encyclopaedic compendia pose an intervention in the historiography of world photography, revealing the investment of time and labour of hundreds of women photobook-makers in an effort to be seen, heard and remembered for what they had to say. The photobook remains a document for personal contemplation and the inscription of meaning, but as women authors have shown us, its address is universal.

Notes

- Anna Atkins, Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions (Sevenoaks, Kent: Self-published, 1843-1853).

- Agnes Cowper was the first woman to be the Official Museum Photographer at the South Kensington Museum in London (now the Victoria and Albert Museum), while Louise Laffon was a successful professional photographer in France, although marking prints with the gender neutral stamps ‘L. Laffon’ and ‘Photographie Lord Byron’, Lederman and Yatskevich eds., What They Saw (New York: 10×10 Photobooks, 2021), pp. 26–27.

- Alice Seeley Harris, The Camera and the Congo Crime (London: The Congo Reform Association, 1906).

- Hedda Walther, Mutter und Kind: 48 Bildnisstudien (Berlin: Verlag Dietrich Reimer, 1930) and Erna Lendvai-Dirksen’s Das deutsche Volksgesicht, (Berlin Kulturelle Verlag-Gesellschaft, 1932).

- What They Saw. Lederman et. al., (2021), p. 70; Lotte Errell, Kleine Reise zu schwarzen Menschen, (Berlin: Brehm, 1931).

- Germaine Krull, Études de nu (Paris: Librairie des Arts Decoratifs, 1930) and Metal (Paris: Librairie des Arts Decoratifs, 1928); Margaret Bourke-White, Eyes on Russia (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1931); also Olga Linckelmann, Über Körper und Seele der Frau (Leipzig & Zurich: Grethlein & Co.,1927).

- Ergy Landau, Enfants (Paris: Éditions O.E.T., 1936); Nell Dorr, In a Blue Moon (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1939); Thérèse Bonney, Europe’s Children, 1939–1943 (New York: Self-published, 1943); Toni Frissell and Robert Louis Stevenson, A Child’s Garden of Verses (New York: U.S. Camera Publishing Corp., 1944).

- Margaret Bourke-White, You Have Seen Their Faces (New York: The Viking Press, 1937); Dorothea Lange, An American Exodus: A Record of Human Erosion (New York: Reynal & Hitchcock, 1939); Kata Kalman, Tiborc (Budapest: Cserepfavi, 1937).

- Berenice Abbott, Changing New York (New York: E. P. Dutton & Company, 1939).

- Helen M. Post, As Long as the Grass Shall Grow (New York: Alliance Book Corporation, 1940); Laura Gilpin, The Pueblos: A Camera Chronicle (New York: Hastings House, 1941).

- Barbara Morgan, Martha Graham: Sixteen Dances in Photographs (New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1941).

- The Polish author Zofia Rydet’s Mały Człowiek (Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Arkady, 1965) focusing on children is acknowledged as being directly influenced by the exhibition.

- Toyoko Tokiwa, Kiken na adabana, (Tokyo: Mikasa Shobo, 1957) and Eiko Yamazawa, Far and Near (Tokyo: Miraisha, 1962).

- Ruth Bernhard, The Eternal Body: A Collection of Fifty Nudes (Carmel, California: Photography West Graphics, 1986).

- Alicia D’ Amico and Sara Facio, Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires (Buenos Aires: Editorial Sudamericana, 1968); Helen Levitt, A Way of Seeing (New York: The Viking Press, 1965).

- Maureen Bisilliat, A João Guimarães Rosa (Sao Paulo: Graficos Brunner, 1969).

- Carla Cerati, Morire di classe (Turin: Giulio Einaudi Editore, 1969); Sara Facio and Alicia D’Amico, Humanario (Buenos Aires: La Azotea, 1976); Diane Witlin, Jaula (Bogoa: Lepetit de Colombia,1974); Mary Ellen Mark, Ward 81 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1979).

- Berenice Abbott, A Portrait of Maine (New York: The Macmillan Company and London: Collier-Macmillan Limited, 1968).

- Evelyn Hofer and V.S. Pritchett, Dublin: A Portrait (London, Sydney and Toronto: The Bodley Head, 1967).

- Abigail Heyman, Growing Up Female: A Personal Photo Journal (New York, Chicago & San Francisco: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1974); Annette Messager, Les Tortures Volontaires, Den Frivillige Tortur (Copenhagen: H. M. Bergs Forlag and Daner Galleriat, 1974); Elsa Dorfman, Elsa’s Housebook: A Woman’s Photojournal (Boston: David R. Godine, 1974).

- Michiko Matsumoto, Nobiyakana Onnatachi/Women Come Alive (Tokyo: Hanashi-no-Tokushu, 1978).

- Miyako Ishiuchi, Zessho Yokosuka sutori/Yokosuka Story (Tokyo: Shashin Tsushinsha, 1979); the exhibition of women artists was Hyakka Ryoran/A Profusion of Blooming Flowers, Shimizu Gallery, Tokyo, 1976.

- Susan Meiselas, Carnival Strippers (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1976); JEB, Eye to Eye: Portraits of Lesbians (Washington, D. C.: Glad Hag Books, 1979); Martha Wilson, Autobiography (Chicago: Chicago Books, 1979).

- Eve Arnold, The Unretouched Woman (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1976); Claudia Andujar, Amazonia (Sao Paulo: Editora Praxis, 1978); Thea Segall, El Casabe (Caracas: Ediciones Fotosecuencia, 1979).

- Nan Goldin, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (New York: Aperture Foundation, 1986); Clarissa Sligh, What’s Happening with Momma? (Rosendale, New York: Women’s Studio Workshop, 1988).

- International Conference, How Do Women Work, London: Tate Modern, 30 November–2 December 2019.

- Hiromix, Hiromix (Gottingen: Steidl, 1998).

- Yurie Nagashima, Kazoku (Kyoti: Korinsha Press, 1998).

- Tokuko Ushioda, Ice Box (Tokyo: BeeBooks, 1996).

- Sally Mann, Immediate Family (New York: Aperture Foundation, 1992).

- Tina Barney, Theatre of Manners (Zurich, Berlin & New York: Scalo, 1997).

- Carrie Mae Weems, In These Islands: South Carolina, Georgia (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama, 1995); Ruiko Yoshida, Haaremu: Kuroi Tenshi-tachi/Harlem: Black Angels (Tokyo: Kodansha, Ltd., 1974).

- Shirin Neshat, Women of Allah (Turin: Marco Noire Editore, 1997)

- Barbara Kruger, Thinking of You (Cambridge: MIT Press and Los Angeles: The Museum of Contemporary Art, 1999).

- Linda Nochlin, Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? (London: Thames and Hudson, 50th Anniversary edition, 2021).

Suryanandini Narain is Assistant Professor of Visual Studies at the School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. She has written extensively on photography in India, especially around themes of women, the family, the home and studio photography, in Marg, Art India, Visual Anthropology Review, Trans Asia Photography Review and other arts journals. She co-edited Framing Portraits, Binding Albums: Family Photographs in India (Zubaan, forthcoming 2024). She teaches courses on Indian visual culture, photography, aesthetic theory and critical writing, and supervises research students working on photography, graphic novels, digital visual cultures and popular art. Her next project is a monograph on domestic visual culture as shaped by middle-class women in India.

Suryanandini Narain is Assistant Professor of Visual Studies at the School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. She has written extensively on photography in India, especially around themes of women, the family, the home and studio photography, in Marg, Art India, Visual Anthropology Review, Trans Asia Photography Review and other arts journals. She co-edited Framing Portraits, Binding Albums: Family Photographs in India (Zubaan, forthcoming 2024). She teaches courses on Indian visual culture, photography, aesthetic theory and critical writing, and supervises research students working on photography, graphic novels, digital visual cultures and popular art. Her next project is a monograph on domestic visual culture as shaped by middle-class women in India.