On the occasion of World Photography Day, I look back at the photographic societies of India, as one of the first formalised communities of photographers, that activated the passion for the field in the country as soon as it arrived. Through the lens of this research project, on Photography and the Magazine in India, the photographic societies, by their creation of official journals, make for an interesting point in history that closely links the developments of photography and printing.

On October 3, 1854, a group of European and Indian gentlemen gathered in the halls of the Geographical Society in Bombay and formally inaugurated the Photographic Society of Bombay (PSB, henceforth). With the motivation to further the Science and the Art of Photography, another commendable achievement of the Society was that it was the first to be established in India and started barely a year after the first photographic society in the world, was established in 1853 in London.

Within this research project, as noted with my earlier piece on the Indian Amateur’s Photographic Album, this dynamic creation of a community, one that engaged in discourse and experimentation, initiated so soon after the invention of the medium, is important to the understanding of communities and networks that formed as a result of these photographic journals. As I shall expand, going further, the printed journal was an essential mode of communication, as early as 1854, which further helps clarify ideas linking photography and the printed medium.

From its inception, the PSB, based primarily on its London counterpart, was built with a similar structure—headed by a Committee which held monthly meetings, organised periodic exhibitions and collected works of members. But due to its early inception within world photographic history, the PSB became an active participant in conversations discussing the advancement of the field, an important part of which was innovations in photographic processes and apparatus. Added to this, practitioners in India were innovating for a very different climatic context as compared to their British counterparts which further outlines the uniqueness of the creation of such a community.

“Success is not always certain when our materials are good but it is impossible when they are bad and the subject is one of such importance that I make no apology for taking up your time with remarks upon it.” remarked Donald Horne Macfarlane, in his paper on landscape photography1, where he details his experiments and challenges with unstable and variable collodions. This might have well been the caveat issued by all photographic society members at the time, but the proclivity towards scientific discussions through papers and experiments was seen as the main purpose of these societies. With the specific knowledge of chemistry combined with the expensive materials required, it is very likely that few were able to perform these experiments and note their observations. There also appears to be no indication of there being a common space where such experiments might have occurred, further emphasising that these activities were privately being carried out by individuals using their own resources. Yet, the growing appetite for photography necessitated the need for an official journal, as a repertory of these experiments, as a common platform affording information to practitioners, as well as a medium to procure necessary material from other outside the country.

The decision to start an official journal, though, was not met with as much enthusiasm at the time. Upon the issuance of the first number of the Journal of the Photographic Society of Bombay (henceforth JPSB), the Bombay Times and Journal of Commerce (subsequently the Times of India) reported their initial resistance towards such an endeavour stating 2: “…we were averse…being aware of how very little original matter of interest it was likely ever to be able to secure and aware moreover that anything worth publication would be accepted by the London Journal.3” The initial suggestions also included printing all relevant information produced by the Society—papers, minutes, announcements, etc—as a part of the Bombay Gazette, as a more cost effective solution, whose printing facility was to be used to produce the magazine. But instead, after much deliberation the journal was produced as a separate entity, one that the Bombay Times and Journal of Commerce would go on to complement for being a “worthy specimen of typographic art.”4 This first issue consisted of the introductory address followed by the proceedings of the inaugural meeting as well as two general meetings.

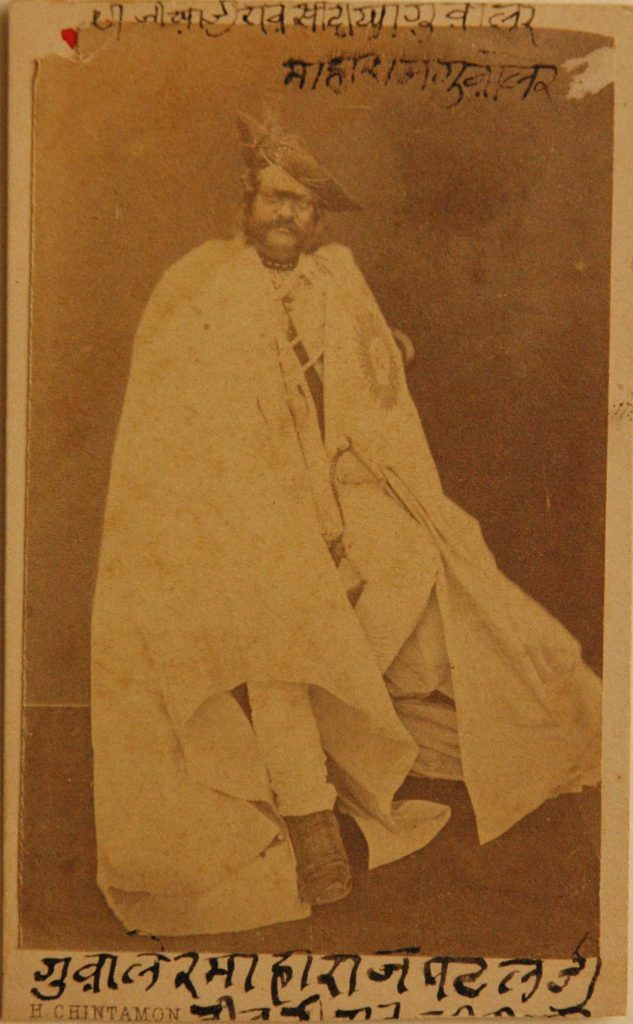

Albumen Print on Carte-de-Visite, c. 1876 – 1878(ACP: 98.60.0356).

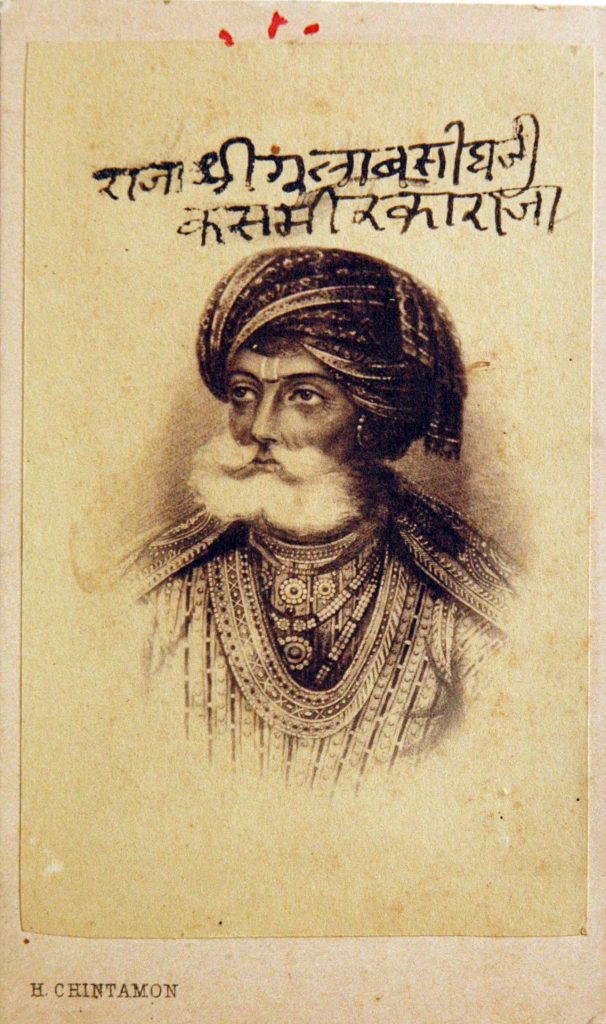

Below: Hurrychand Chintamon, Bombay. Raja Sri Gulab Singh Ji of Punjab

Albumen Print on Carte-de-Visite, c. 1876-1878

The Alkazi Collection of Photography (ACP: 98.60.0355)

Recto & Verso

With the participation of some notable practitioners such as Capt. HJ Barr, WHS Crawford, Dr Narayan Dajee, Dr Bhow Dajee, Dr G Ballingall, Ardasheer Framjee, William Johson and Capt. Biggs, amongst several others, the journal featured, though their papers, strides within Indian photography. For example, Capt Barr’s invention of an appendage for a view camera capable of holding unlimited prepared sheets which could be exposed one after another without being taken out from the camera or Crawford’s improvement on the waxed paper process for India’s hot climate or his plans for a new kind of camera that would shorten the exposure time for Daguerreotypes, which could help produce greater details, are all examples of such efforts. The process and plans for each of these was explained in great detail within the journal and would also be republished in journals of other photographic societies. In particular, the Liverpool Photographic Journal frequently published proceedings and discoveries being made through the Bombay Society. Thus, the journal became a medium through which photographic societies between India and England could communicate with one another, often, also contributing to each other’s journals.

(ACP: 99.02.00400

Vitthala Temple, Gopura and Dipa-stambha, Vijayanagara, Waxed-Paper Negative, 1856, (ACP: 99.01.0054)

The Alkazi Collection of Photography

Calotype images by AJ Greenlaw were exhibited as a part of the 1856 exhibition by the Bombay Photographic Society

Apart from discussions on process, the journals also reported on exhibitions, which were a yearly feature of these societies. An exhibition by the Bombay Photographic Society held in 1856, reportedly consisted of “negatives by Calotype, Waxed paper, Flacheron’s 5, Collodion and Albumen processes as well positives taken by Collodion and Albumen processes and Daguerreotypes.” The exhibition, in a way, was a celebration of successes of these various experiments—their accuracy in terms of tonality and sharpness. The best images of the exhibition, according to the report, were those that had been finished with utmost care and artistic execution, with regards to point of view, tonality and time of exposure. By these metrics, Narayen Dajee’s photographs of scenery and architecture in Gujarat were reported to be “too warm to suit our taste altogether.” 6

With the perfecting of the science of creating images, photography began to be seen as a utilitarian engagement useful to other governmental activities, such as cartography or documentation. Rather than the expensive process of lithography or line engraving used to make copies of maps of different regions used by the Survey Office, photography finally began to be used instead as a more cost effective process. A formal position of a Government photographer was created, whose role would have likely been documentation of various aspects of this new land—from its people to its geography. Capt Biggs as the first photographer in this position photographed the ruins of Beejapore extensively, which were then included in an exhibition by the Photographic Society in Bombay and acquired by the society for educational purposes. Apart from papers, the PSB was also interested in acquiring different kinds of images from its members as a learning aid for other practitioners. This might have also been a useful tool for the Photography instruction class that had been started at the Elphinstone Institution in Bombay not long after the creation of the PSB and was being conducted by a member, WHS Crawford.

By 1856 the journal had already begun to face a shortage of content and willing contributors. Addressing this in a notice, the writer attributed the lack to practitioners being too deeply engaged in the practice of the art and thus unable to sufficiently reflect on their process. Outdoor photography, in the form of long expeditions, though already wildly popular, might have become a more popular exercise as photographers such as Samuel Bourne began taking their cameras on treacherous expeditions like his three up to the Himalayas. The expanded uses of photography were being discussed, as in an issue of the JPSB, where the editor “strongly recommended to have photographs taken of our palms and other conspicuous forest trees, for the purposes of general instruction. There are few things people would desire more to carry with them than such a collection as these would form, nothing would be so valuable as a small portfolio of them to a traveller on his first visit to India.” 7

My research has been unclear about how long the Journal lasted, but it is clear that the precedence of a printed medium as a mode of communication and exchange facilitated the establishment of many of the photographic journals that were yet to come. Though the scientific nature of the printed medium changed drastically, to discourse around the more artistic implications of photography, the expectation of a community and a platform that privileged discourse and debate was a very helpful one. In general, the formation of formalised photographic communities through societies was an important step in the development of photography but preserving the journal, or a unique printed form of communication necessitated further inventions in printing. As might be evident through discussion of these journals, they were predominantly text-driven, and photographs were retained for commercial albums 8, private albums or other forms such as the carte-de-visite that would develop in time. But with improvements in printing technologies, being able to print images alongside text, the printed photographic journal now had the opportunity to be a focussed space for the discourse around photography.

As I go on, focusing on some of these later magazines that developed either within or independently of photographic societies, I shall keep returning to some of these precedents set by some of these earliest photographic societies to understand the different modes of engagement and discourse within photography.

- Journal of the Bengal Photographic Society, 1857

- May 2, 1855, Bombay Times and Journal of Commerce

- The official journal of the Photographic Society of London

- January 27, 1855, Bombay Times and Journal of Commerce

- Named after Frédéric Flachéron, who experimented with the Calotype to create his own process involving painters’ materials for manipulation.

- Cursory Notes taken at the Exhibition, Bombay February 1856, JPSB.

- December 6, 1856, Bombay Times and Journal of Commerce

- See Indian Amteur’s Photographic Album.