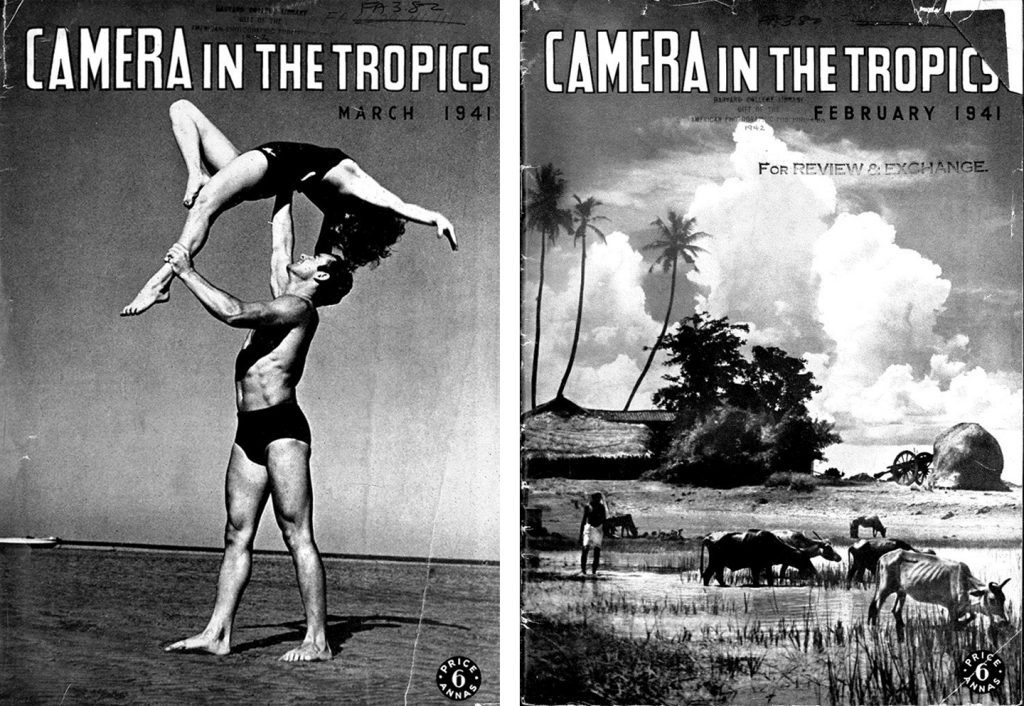

Left: Cover March 1941. “Balance” by Gulamali Habib, Image courtesy: Harvard Fine Arts Library archives.

Right: Cover February 1941. Image courtesy: Harvard Fine Arts Library archives.

Within this ongoing research on ‘Photography and the Magazine in India’, one magazine in particular keeps rearing its head as a fascinatingly dense source of material on the state of these arts at the time. Thus, an introduction to a magazine that in the 1940s first created the idea of a dedicated reading public for photography.

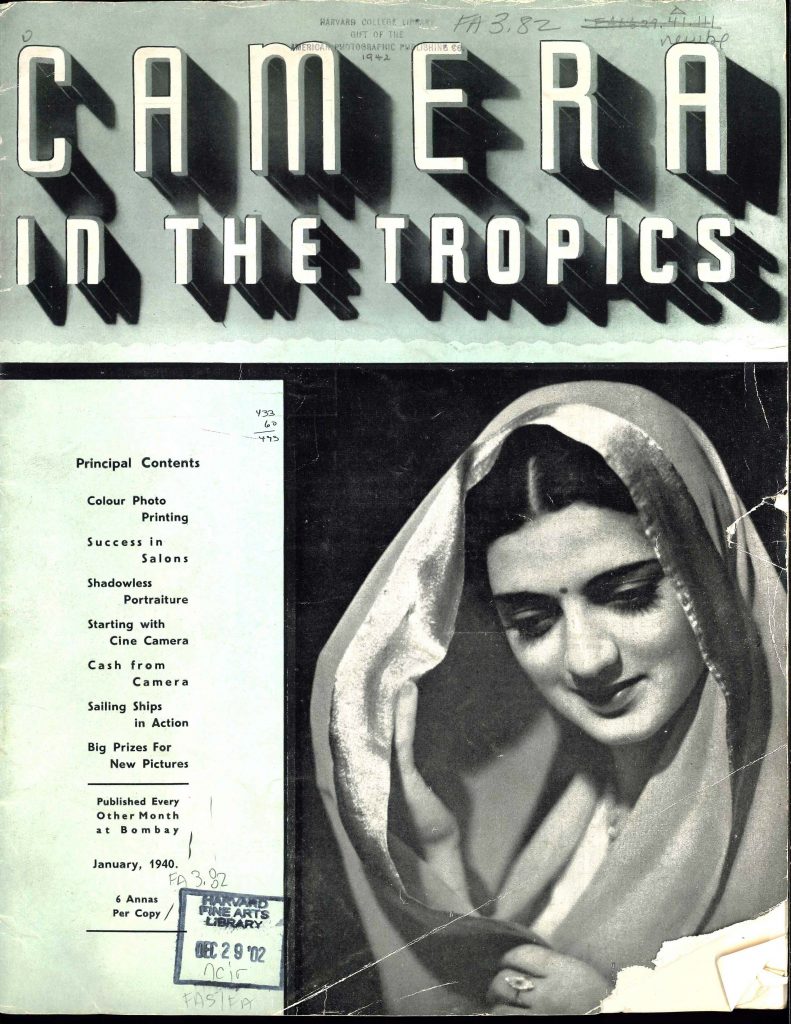

Started in January 1940 by the entrepreneurial Ambalal Jhaveribhai Patel (AJ Patel), Camera in the Tropics was self-styled as the “first photographic journal of its kind”. Patel, founder and owner of a successful camera equipment business—the Central Camera Company—and a state-of-the art studio and processing facility for still photography and cinema film, began the magazine as an “interesting magazine for Professional and amateurs—cine and still workers.”

By this time in the 1940s, photographers as a formal group of professionals had thrived for a long time, under the aegis of several photographic societies across the the country, Within Bombay, these were the Photographic Society of Bombay (1854), the Bombay Amateur Photographic Society (1886) and the more recent Camera Pictorialists of Bombay (1932) and the Photographic Society of India, Bombay (1937). Each played a slightly different role in the advancement of the photographic arts, but none had publications at the time. The efforts of the Camera Pictorialists, as evidenced by their name, were aimed at assisting in the recognition of pictorial photography as a form of art, and creating a space for knowledge-sharing about and appreciation for the same. To this end, they held frequent Salons of their members’ work. While these were handsomely attended, we aren’t aware of a dedicated publication or journal produced by the group, unlike the earlier photographic societies. The motivation behind the Photographic Society of India was to be a central body for the photographic community in India, that provided production assistance to individuals through facilities like studios and dark rooms. It would take them till the 1950s to found their official magazine, titled Click. The year 1938 also saw the formation of the Amateur Cine Society, a group that brought together amateur filmmakers and promoted the appreciation of amateur cinema making.

Against such a backdrop, Camera in the Tropics was necessary and timely, in marking this dynamic and thriving phase within film and photography, encapsulated within its tagline.

Initially published every other month, at a price of eight annas, Camera in the Tropics featured a diverse list of articles—from concepts behind photo-montages and night time photography, to reports on the activities of the Societies mentioned earlier. It is undeniable that the emphasis on pictorialism and its popularity as an art form influenced the magazine and its features. For its first cover, in January 1940, the portrait of a woman graced the cover—with coy downward gaze, cloth demurely pulled around her head, beautifully lit to reveal delicate tonal shifts in the greys. Similarly, an image featured alongside the table of contents (by Stanley Jepson, whose unique role in the history of this magazine I’ll elaborate on in just a bit), shows a young girl, bedecked with jeweled headdress and necklace, shrouded in a sheer fabric—another specimen of the play of light and shadow that was a characteristic feature of pictorialism. Even the articles were invited from noted pictorialists of the time such as AL Syed, T Kasinath and G Thomas amongst others. That said, it wouldn’t do to not point out the eclectic assortment of articles the magazine was also featuring, such as “Better Dog Pictures” or “Stalking the Kiddies”. Yet another regular feature in most issues was a competition open to the readers of the magazine, with no restriction on subject, with a cash prize awarded to the winners. As the magazine progressed, and the frequency of photographic competitions and exhibitions increased, there was also a dedicated column to upcoming events—an entire section dedicated to announcements of national and international photographic exhibitions. It is a testament to the magazine’s commitment towards spreading photographic knowledge and creating opportunities for exposure, that listing of these exhibitions and salons ranged from the First Exhibition of Photographic Art organised by Niharika, the Club of Gujarat Pictorialists, founded by artist Ravishankar Raval in 1938 to the 8th New Zealand Salon of International Photography. Thus with a diverse and wide-ranging variety of entry points into photography, spanning news and editorials, it seems safe to conclude that Camera in the Tropics, as an affordable bi-monthly magazine, was one of the first editorially-driven popular magazines for the photographic arts.

My investigation of this magazine and its roots took me to Bombay (now Mumbai) in 2020,where I was able to locate the Central Camera Company in the Fort Area of the city. Much to my surprise, in the same Saheb building where the company still runs today on the third floor, exists the Photographic Society of India on the fifth. Though just as an interesting observation, this brings me to several overlapping worlds that seemed to converge within the Camera in the Tropics. AJ Patel, as mentioned earlier, was a camera equipment dealer, who soon branched out into film equipment, seeing its great business potential. He was also one of the first members of the Amateur Cine Society set up in 1937. Thus it’s little surprise thatCamera in the Tropics incorporated both the cine and the still forms of the art One of the initial Presidents of the cine society was noted pictorialist and co-founder of the Camera Pictorialists of India, JN Unwalla. Thus, we begin to see major overlaps between the worlds of photography and cinema—ones that the Camera in the Tropics seemed to have formalized. Yet another member of this group was the then editor of the famous illustrated magazine, the Illustrated Weekly of India (commonly the Weekly), Stanley Jepson. Jepson, as a photographer in his own regard, and as an author of the book Indian Lenslight was instrumental in having created a substantial space for photography with the Weekly. Thus it seems natural that Patel would have sought out Jepson as a contributor and advisor for the magazine. However, the ties between the Camera in the Tropics and the Weekly run deeper. Not long after its commencement, the editorial charge and proprietorship of the Camera in the Tropics shifted from Patel to Horace J Collett, a journalist for the Illustrated Weekly, and we also see the byline for the magazine include “ c / o The Illustrated Weekly of India.” Thus, there is clear evidence that Camera in the Tropics created a common meeting ground for professionals working across photography and film. In the process, it also brought together audiences interested in the two fields, creating a larger dedicated public for these art forms.

Running successfully for well over a decade (perhaps two), the magazine’s frequency increased from once every two months to monthly during this period, a testament to its continuing popularity, and a stark contrast to the usual trajectory of niche magazines today Not long after its launch, the photography world confronted World War II, which suddenly created new spaces for the photographer, not just within the space of photojournalism but also within publicity (or perhaps, propaganda) efforts undertaken by countries. A report from the Times of India (24 February 1943) points to the Camera in the Tropics as proof of the continuing interest in photography as a hobby during these trying times. Collette, then editor of the magazine, was quoted crediting the war as a “stimulus” to all branches of photography and for the revolutionary advancements to photographic equipment that occured at the end of the war. The magazine had quickly become a definitive voice within photography—not only in India, if the advertisements from the time are to be believed but across the East. Even the title of the magazine alludes to a larger geographic region, while still being a magazine on and about India, signalling some form of an outsider’s gaze. As we explore the magazine further, it is unquestionable, given its long print run, that it will prove to be a rich document of the photographic community and its dedicated publics at the time.

I will be delving further into content from the magazine as a part of subsequent texts.

Further reading:

- For AJ Patel’s rather fascinating journey with film, as an educative films producer and later a pioneer in colour film processing read this excerpt from an unpublished biography of Patel: https://thewire.in/film/how-one-man-efforts-made-colour-popular-in-indian-cinema-ambalal-patel

- Accounts of amateur cinema making and the activities of the Amateur Cine Society featured in several international magazines dedicated to amateur film such as Home Movies (1945) and Movie Makers (1951)