Previously, while thinking about Photography and the Magazine, I have tended to focus on individual magazines, their content and relationships to photography and its evolution. But this week, I think about the nature of magazines, their ephemerality and seriality, and what clues that might hold to photography’s status in India during the 40s and the 50s. Instead of focusing on the reading public created by magazines, I focus on the group that lead to the creation of these magazines.

While introducing Camera in the Tropics, I briefly touched upon the various social networks, at the intersection of which the magazine stood. Here, I expand on some of these networks—primarily, The Amateur Cine Society (ACS) and the Photographic Society of India (PSI), Bombay—further, and use them to expand on the nature of photographic practice at the time—a time of true collaboration and experimentation.

In her introduction to Artists’ Magazines, an Alternative Space for Art, historian Gwen Allen writes, “Like the relationships and communities they embody, artists’ magazines are volatile and mutable.They seek out the leading and precarious edges; they live at the margins rather than in the stable and established center. They thrive on change and impermanence, favor process over product, and risk being thrown away. They court failure.” In essence, Camera in the Tropics, was that artists’ magazine, one that was formed by an enthusiastic hobbyist, but sustained by a network of photographers and artists who wished to explore the medium further, and embodied the spirit that Allen refers to—of favouring process over product.

The October 1950 issue of Camera in the Tropics notes photography’s popular status—no longer a luxury hobby of the few—and yet also acknowledges that it was more expensive than several other hobbies of the time, philately being a popular comparison. Thus the motivation behind the magazine was to make photographic knowledge, which otherwise would only be made available through expensive books, widely available. The focus was on sharing the latest developments in techniques within photography, its printing and equipment. And this was information that these practitioners were exploring within their own practice as well through different societies.

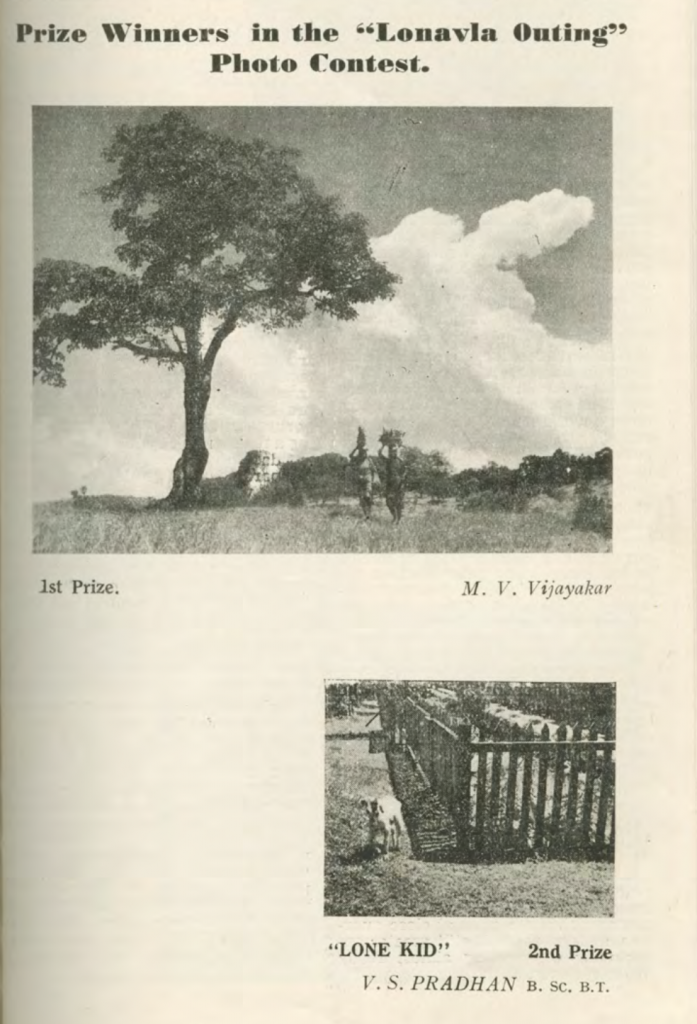

In an earlier piece, I had written about the several overlapping worlds that seemed to converge within the Camera in the Tropics and that is further evident in the kind of activities undertaken by the societies which shared a lot of members in common. Very early on the PSI as well as the ACS began providing equipment on rent that members could use for their own work—from meters for shot readings to “Saddle Back” wooden tripods. This fit with the range of activities offered as well, such as outings or sessions where members would be invited to explore different equipment together, as a way to learn from each other. This would extend to events like “experimental nights” at PSI, where members attempted multiple toning of print, or screenings at the ACS of mostly silent amateur films, or more interesting, debates on topical subjects such as “Black and White vs Colour”, one of many events that was opened to still photographers as well as filmmakers. And geographically it isn’t hard to imagine that these societies were overlapping since all of them were housed at one specific building, the Sahib Building on Hornby Road (now Fort Area, Bombay) almost throughout the time they were alive.

If in the real world, photography and amateur filmmaking and their practitioners were cultivating a robust experimental space, the Camera in the Tropics became the space in print that documented these activities. The magazine featured news from other prominent photographic societies such as the ACS, PSI featured as regular sections, which expanded to include foreign societies and exhibitions. “Books you should read” featured recommendations from the editor on the newest and most sought-after magazines and publications on different techniques. Notable practitioners such as JN Unwalla, MV Vijayakar, HA Kharas, KA Patel and several others populate the pages of the magazine as winners of competitions or as administrative leaders of different societies. It is hard to determine how many members might have been a part of these groups, but with at least three or four new members being announced each month as a part of the issue, one could assume that it was a thriving community. With the acknowledgement that photography was still considered expensive, the PSI Improvement Fund was set up as a way to provide members with state-of-the-art equipment and facilities, for experimentation and furthering of the artform.

Thus, the three photographic societies, and alongside it, the magazine, might be thought of as an alternative space to a culture of photojournalism and commercial photography that also existed by this time. While these were seen as ways to monetize ones photographic skills, initiatives such as these were kept alive as spaces for experimentation and collaboration.

All images courtesy: George Eastman museum