STAGING TRANSITIONS – THEATRE OF THE 90s IN INDIA

BHARAT BHAVAN – STATE LEVEL THEATRE UNDERTAKING.

On the 25th anniversary of Indian Independence in 1972, Government of India recommended all states to set up institutions dedicated to promotion of cultural activities, and provide space for collaborative endeavours among different aspects of art and culture.1 This was beginning of the move from a socialistic, centralised state model to a market based and decentralised governmental model. These processes culminated in structural readjustment of India’s polity and economy in the 8th and 9th decades of the 20th century. With a mandate to initiate and promote decentralisation, artistic fervour and incorporate regional voices in the cultural movement of the nation, the government proposed the setting up of cultural centres at the state level. Along with centrally funded and controlled state wings of the Akademis, the states started instituting provincial-level cultural institutions. Bhartendu Natya Akademi in Uttar Pradesh, Odisha Sangeet Natak Akademi, Bharat Bhavan in Kerala, Bharat Bhavan in Bhopal and Rangayana in Karnataka are some of the examples from among many institutions being set up at the state level post 1970s.

Bharat Bhavan, designed by Charles Correa was set up in 1982 as a multi-cultural centre consisting of Roopankar – a museum of art, Anhad – music centre, Vagarth – centre for Indian poetry and Rangmandal – the theatre repertory. The centre has an outdoor stage – ‘Bahirang’ and an indoor stage – ‘Antarang’ to stage performances. The centre was registered under the MP Public Trust Act through legislation in the Madhya Pradesh assembly and was led by the three life trustees – Arjun Singh (then Chief Minister of MP), Ashok Vajpayi (Joint Secretary Culture) and Jagdish Swaminathan (an eminent folk artist). The Bhavan was instituted with aid from both central and state governments, providing a one time corpus that was replenished every year by the state government grants.

The state of the then undivided Madhya Pradesh (now Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh) had a rich theatre movement primarily composed of folk forms, and ritualistic presentations like ‘Naacha’, ‘Pandvani’ and ‘Maach’. Rangmandal – Bharat Bhavan’s theatre repertoire was the first government-funded theatre repertoire based in Madhya Pradesh. It was envisaged to provide a sustained theatrical tradition in the state, formalised learning and development space for the artists, wherein they were exposed to not just regional, but various other national and international theatre forms, techniques and training methods. On the opening of the Bhavan, Peter Brooke carried out a 4 day workshop on the premises. Fritz Bennewitz collaborated frequently with Rangmandal (1983, 1985, 1986, 1987 and 1989). The initial years of Rangmandal saw an intense national fervour with strong folk roots, under directorship of B.V. Karanth. Initially, Rangmandal planned to carry out a major production every year, along with fringe productions. This was an initiative to provide Rangmandal a national reputation as well as opening avenues for emerging artists. Apart from B.V. Karanth, Alakhnandan was a major director at Bharat Bhavan. Alakhnandan hailed from Madhya Pradesh and he was appointed to Rangmandal as a director in order to provide space to local people to grow and lead the Bhavan in the future. Alakhnandan not only employed the Chhattisgarhi dialect in the productions, but also incorporated the folk form of ‘Naacha’ and employed local artists in the production. Habib Tanvir was the last director of the repertory, appointed in 1996. His tenure was marked by internal conflicts among the repertory. He tried to enlarge the scale of productions. For the purpose of productions like ‘Jis Lahore Nahi Dekhiya O Janmaye Nahin’ and “Mudrarakshasa’ he employed members of his ‘Naya theatre’ along with the actors of the repertory.

Bharat Bhavan was conceptualised with a vision to forge a two-way communication channel – providing a platform to various local artists and art forms and interact with artists of national and international repute. Apart from regional, national and international collaboration, the Bhavan focused on interdisciplinary collaboration. The presence of centres for different art forms aided in the exchange of ideas as well as collaboration amongst varied art forms. For instance, the play ‘Shastra Santaan’ was written by Rameshwar Prem as a residential playwright in the Bhavan in the 1980s, and later was produced by Rangmandal under B.V. Karanth’s direction in 1990.

The evolution of the vision of Bharat Bhavan as understood by looking at its festival brochures provides an insight into the impact of central policy change at the state-level institutions. This helps us better understand the impact of union policy as mediated by decentralisation. The three brochures of Bharat Bhavan theatre festivals (accessed from Alkazi Theatre Archives) from 1985, 1991 and 1992 help us in understanding this shift. The editor’s note from the 1985 brochure focuses on finding an Indian theatre, i.e. an amalgamation of past and contemporary, reflecting the larger national narrative of forging an ‘Indian’ identity and creating a ‘national theatre’ on this conceptualized identity. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the national Five-Year plans postulated setting up of regional centres that could be nodal agencies for providing funds and promoting culture at the state and regional level. Reflective of this policy narrative, the editor’s note in the brochure of ‘Bhopal Natya Utsav’, 1991 focused on providing resources to the local groups to blur the distinction between professional and amateur theatre. Similarly, the 1992 ‘Bahubhashiye Natya Samaroh’ focused on inter-regional collaboration, and forging national identity that is a cumulation of the multiple regional diversities. This is reflective of national plans of the time that focused on greater intercultural activities spearheaded by regional nodal centres.

Slide-1Brochure of Rangmadal stating the vision of the repertoire, 1982.

Slide-2The brochures of the festivals organised by the Bharat Bhavan, Bhopal in 1985, 1991 and 1992.

Slide-3Bharat Bhavan as part of festival of France in India, 1990.

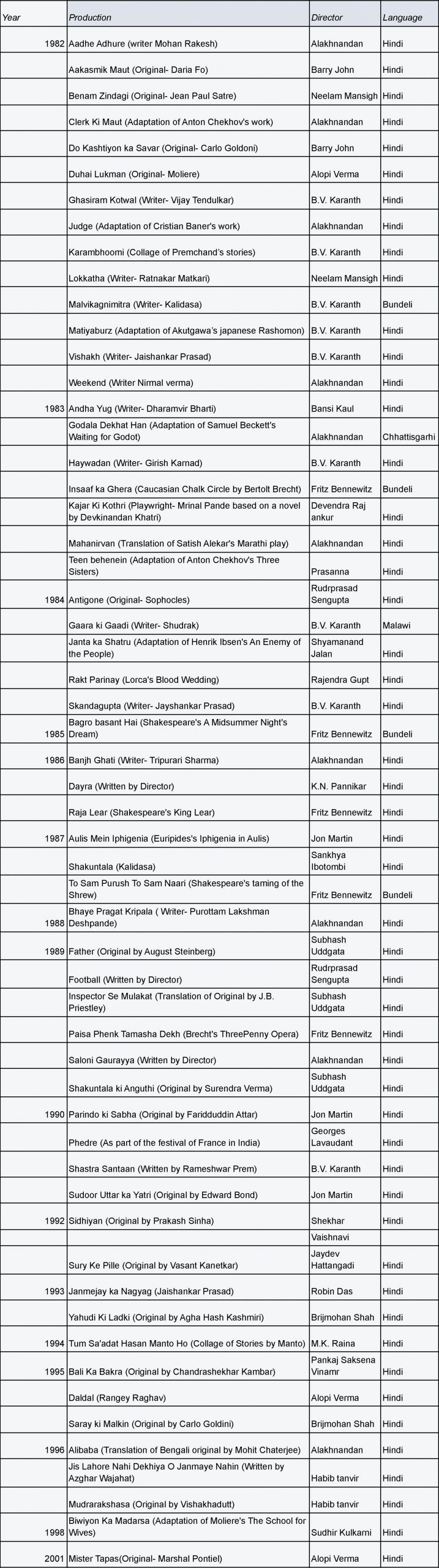

Table 1- List of plays performed by Bharat Bhavan Rangmandal 2

Rangmandal performed Vijay Tendulkar’s ‘Ghasiram Kotwal’ under the direction of B.V. Karanth as its first production at the inauguration of Bharat Bhavan in 1982. In Kalidasa’s ‘Malavikagnimitra’, Karanth experimented with form and language. To emphasise the class distinction, the yogini in the play spoke the formalised Hindi, whereas the other characters spoke in Bundeli – a local dialect. At the same time, the protagonist used the classical dance forms of Kathak and Bharatnattyam, and the other characters employed folk forms from Madhya Pradesh. Such a direction brings to fore the unequal power relation present between official versions of languages and the various dialects, as well as the relation between classical and folk forms.

Repertoire of Bharat Bhavan relied heavily on utilising local art forms and artists in training as well as performers. Several European and Indian classics were translated into local dialects and performed. The Rangmandal followed a strict routine of training and performance, where the artists were trained in music, dance and stage duel. While focusing on strengthening the theatre movement present in the state, Rangmandal focused on incorporating regional folk forms, working towards their development and syncretic creation with western and contemporary styles. It aimed at taking the established urban theatre to the margins as well as bringing margins to the urban core. It was also able to direct international collaborations and funding to state and regional levels, thereby broadening the resource base and increasing the absorbing capacity of artists in the formalised sector. The success of the Bhavan is a direct evidence of sustainability and the need for implementation of Haksar committee recommendations of decentralisation and provision of autonomy to the cultural institutes.

Bharat Bhavan reached the peak of its glory in the 1980s. However, during the 1990s it started to fall apart. After the change in government in 1993, a two day conference – ‘The Autonomy of Art Institutions: perspective Bharat Bhavan’ was convened by the Madhya Pradesh government in 1994 to decide the future course of Bharat Bhavan. It included reputed artists of the country like Habib Tanvir, Namvar Singh, Krishen Khanna, Ayappa Panikar, Subhash Mukhopadhyay, Kishori Charan Das and K. Satchidanandan. In 1995, as per the recommendations from the seminar, the government granted autonomy to the Bhavan, and it was registered under the Indian Trust Act. However, the main source of funding remained the state government. Of an annual budget of Rs 1.30 crores, 50 Lakhs came from the state government and rest were drawn from the interest on the corpus. Also, of the 15 members, the state government had the right to nominate 7 members, central government to nominate 3 members, and these 10 members in turn nominate the remaining 5 members. These two facts limited the autonomy of the Bhavan. Soon after gaining autonomy, the financial crisis started affecting the Bhavan.3,1 With rapid changes in Madhya Pradesh politics, very few trustees were able to complete their tenure, and political favouritism and not merit became a decisive factor. Soon Rangmandal ceased operations.

All image courtesy: Anand Gupt collection/ Alkazi Theatre Archives

Notes-

- ‘No Takers for Bharat Bhavan’ published in The Hindu, July 1994. Accessed from Sangeet Natak Akademi library.

- Data from the ‘Bharatiye Rangkosh: Hindi Sandarbh’ volume 3 published by National School of Drama. Accessed from Sangeet Natak Akademi library.

- ‘Bharat Bhavan Seeking a Break from its Past” published in The Statesman, January 1996. Accessed from Sangeet Natak Akademi library.