STAGING TRANSITIONS – THEATRE OF THE 90s IN INDIA

THE CHANGING POLICY PARADIGM

In the Indian context, the decade of the 1990s is often studied in conjunction with major economic and political policy changes and structural adjustments that altered the socio-political and cultural landscape of the nation. While the economic policies of Liberalisation, Privatisation and Globalisation aimed at integrating the nation with the international capitalistic model of market operations, the 73rd and 74th amendment to the constitution introduced the local government in rural and urban bodies. Both these policies were aimed at one common agenda – limiting the centralised control of the union government over the national and regional economy and polity. While the structural adjustments in the economy spearheaded socio-political changes, the policy modifications themselves were a result of rising urban middle class, influence of western model of capitalism, and the discontent with a centralised welfare state model. The impact of overarching changes in the political environment and policies was also reflected in the cultural field.

Post independence, India did not have a dedicated cultural policy, broad visions coherent with a nationalistic mission guided the cultural sphere instead of a formal policy. This is well exemplified in the Drama Seminar held by the Sangeet Natak Akademi in 1956. The idea of culture was based on identifying the ‘national’ in the existing culture (national dance forms, national theatre, national music, national poetry and so on). Here the impetus was towards creating a national theatre at par with the European understanding of nationalism, drawing inspiration from the European model of nation-states with a unified identity, linear history and the idea of a common past. The government invested in setting up institutions like the Sangeet Natak Akademi (est. 1952), Sahitya Akademi (est. 1954), National School of Drama (est. 1959, autonomous since 1975), all based in Delhi. It was believed that these institutions, through development of their regional cultural wings, should be leading cultural dialogue and developing the cultural sphere of the nation. During the Drama Seminar, discussions on different regional forms and different language theatres repeatedly referenced to their Sanskritic roots and provided evidences of the presence of techniques as encapsulated by the ‘Natya Shastra’. The identity of Indian drama was attempted to be constructed as deriving inheritance from glorified ancient past and the ancient past was modelled on Sanskritic cultural forms.

jpg2pdfImage 1 and 2 – The scepticism regarding the feasibility of the regional centres of Akademis from ‘How apolitical is cultural policy? The NSD example’ by Biren Das Sharma in ‘Seagull Theatre Quarterly’, Issue 6, August 1995. Image courtesy: Seagull Theatre Quarterly: Alkazi Theatre Archives.

Image 3 – A view on what National theatre actually means from ‘Is there or should there be a National Theatre in India’ by G.P. Deshpande in ‘Seagull Theatre Quarterly’, Issue 6, August 1995. Image courtesy: Seagull Theatre Quarterly: Alkazi Theatre Archives.

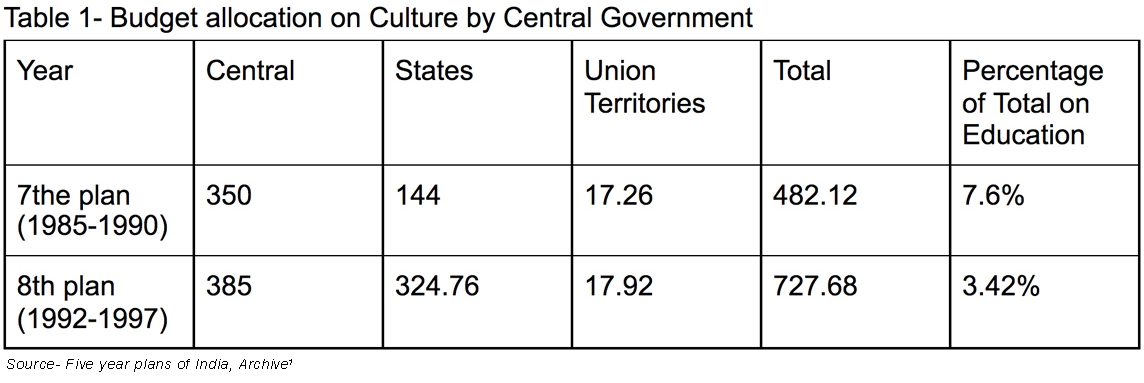

Culture as a policy arena was categorised under the category of Education. Post-formation of Indian Council for Cultural Relations (ICCR, est. 1950), culture as part of foreign policy and relations also appeared in the ministry of external affairs list. An analysis of the five-year plans, the guidelines for policy and development of the country, helps in understanding the evolving government policy stand towards culture. In the first five-year plan (1951-1956) there was no mention of culture as an arena requiring government support. From the second plan (1956-1961) onwards, a short analysis of culture under the head of education appeared in the planning document. Until the 6th plan, all the plans talked about setting up national institutions like Sahitya Akademi, Sangeet Natak Akademi, etc dealing with creation and promotion of ‘national art’ forms. A large section was devoted to development and promotion of Hindi. The 3rd plan (1961-1966) talked in brief about the international cultural relations. From the 6th plan (1980-1985) onwards, culture started assuming bigger role in the national planning. The policy purview broadened from just setting up and promoting certain central institutes and Hindi. A comparative analysis of the approach towards culture in the 6th (1980-1985), 7th (1985-1990), and the 8th (1992-1997) national plans gives insight into the changing policy paradigm. These three plans along with two interluding annual plans (1990-1991 and 1991-1992) cover a period of more than 15 years. The 6th five-year plan (1980-1985) gives minuscule coverage to culture – which only appears in the plan as a vehicle of furthering other agendas and sectoral goals enlisted in the plan. The 6th plan stated that the major role of culture was to promote national pride and integration. It must be noted that though culture was identified as instrumental in fulfilling other motives, it was not given substantial support for sustenance. This role assigned to culture was taking place at a time when both the ontological and epistemological basis of national culture itself were being questioned. This was the time when questions such as “What is the National Culture?”, “Can there be a National Culture?” and “How to define National Culture?” were being raised. The 7th and the 8th five-year plans gave considerably more emphasis to culture as a sector of polity having its own importance. The importance and need to establish the zonal cultural centres to bring about cultural awareness and participation was formulated in the 7th five-year plan. This plan laid emphasis on giving impetus to regional and local art forms. This represents a slow departure from the idea of a centralised nationalistic vision of the 6th plan. The 8th plan took this idea to a further institutionalised level where the plan stated the efforts required towards less centralised control, greater autonomy and provision of funds to the state and local bodies to work in the cultural sphere. The overview of the 8th five-year plan clearly states the need to de-beauracratise the cultural policy and the need to incorporate the Haksar Committee recommendations. The Haksar Committee report submitted in the year 1990 is an important government document for understanding the cultural space in India. The committee addressed the problematic nature of the concept of a singular ‘national’ in India given its diverse traditional cultures. Instead, it laid emphasis on regional institutes with a focus on local languages, traditions and forms. The report talked in detail about the need for decentralisation of the National School of Drama which till then was the sole national institution for theatre training with Hindi as sole medium of training. It discussed transforming the NSD to an advanced level training space and transferring the basic training to regional centres. The report also discussed the autonomy of the Akademis and NSD, wherein instead of being a patron, the government would become the fund provider with the decision making regarding fund utilisation and allocation to rest with the governing body of these institutions. The report formalised long-standing concerns and suggestions of the cultural practitioners and scholars.

jpg2pdfImage 1, 2 and 3: Cultural aspect in 6th (1980-85), 7th (1985-1990), and 8th (1992-1997) five-year plans1

Slide 2B -FImage 1: Newspaper report on the Haksar Committee recommendations in Times of India, July 26th, 1990. Image Courtesy: Anand Gupt Collection/Alkazi Theatre Archives

Image 2: Draft of National Policy on Culture from the Annual report of Ministry of Culture, 1993-94

The 8th national plan overview further identified the need to curtail central control over the cultural space through the setting up of regional branches of central institutions. It focused on increased cooperation and collaboration between the local governments so that they could become the decisive forces of cultural growth. This is reflective of the major policy changes of the 1990s wherein the decentralisation of political power was finding an institutionalised expression and the community led development against centralised planning was gaining momentum.

The structural changes opened up the Indian economy for foreign direct investment and business operations. The government withdrew its shares and loosened its control over various industrial enterprises granting them autonomy. Similarly, several industries that were earlier reserved solely for government operations were delisted and opened up for private business. While its control loosened over the economy through disinvestment and privatisation, the government remained the sole policymaker in deciding the operation of the private sector. It was also responsible for safeguarding small and medium scale businesses who were ill-equipped to compete with international and large businesses. The government tried balancing the roles of a welfare state with a focus on distributive justice and that of the modulator of a capitalistic privatised economy.

Instead of directly creating infrastructure or providing services, the government started partnerships with private enterprises and extended grants, subsidies and aids to help private enterprises. One such public-private partnership having a direct impact on the cultural field was the setting up of the National Cultural Fund in 1996. Through formation of this fund, government initiated involvement of private institutions and individuals as equal partners of government in management of cultural heritage of India. Through this fund the private institutions and individuals were able to contribute by either undertaking the restoration and preservation directly as per the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) guidelines or fund the projects undertaken by the ASI. Although the fund focused primarily on archaeological heritage conservation and promotion, it also funded projects on theatre performances, dance, music, etc where they supported its primary aim. This fund embodied the spirit of a modified Indian economic structure. The introduction of the fund reads:

“National Culture Fund constitutes an important departure from the implementation strategies of the Government, which hitherto was thought to be solely responsible for providing administrative and financial wherewithal for culture related endeavours in the country.”

Slide-AIntroduction of National Cultural Fund2

The creation of the National Cultural Fund can also be analysed with regards to the changing role of culture in the evolving foreign policy and diplomacy of the country. Recognition of culture as ‘soft-power’ in the foreign policy of the 1980s gained momentum in the 1990s. The preservation and promotion of culture and heritage was part of a larger image creation and diplomatic strategy. This can be seen in continuation of the events that were initiated with the organisation of The Festival of India abroad in the 1980s. The motive behind organising these festivals as stated in the Ministry of External Affairs report reads –

“The main objective of the Festival is to bring into focus, the richness and variety of the cultural heritage of India and the progress India has made in the fields of science, industry and technology, since independence.”3

Lots of focus was given to classical and folk art forms as well as presentation of scientific achievements. These festivals were recognised as the one of the largest celebrations of any country abroad. They were organised with a dual motive – firstly, to create an image of india as a country with a glorious past and a promising future and secondly, to attract foreign investment in the country. These festivals were organised with the help of private endowments along with a large governmental expenditure. At the same time, the role of the Indian Council for Cultural Relations was also sought to be re-oriented. As part of 9th report on Indian Council of Cultural Relations, the need to re-orient the activities of ICCR towards prompting and aligning with the foreign policy4 was emphasised and was accepted by the government. The report laid emphasis on the use of culture as a ‘soft-power’ and part of Indian diplomacy to create and promote country’s own narrative and also as a corrective measure against distortion by the vested interests.5

Despite the possibility of private funding for promotion of culture, the central government remained the largest fund provider responsible for allocation of the funds to the states to carry out their cultural programmes. Despite the union budget being the largest source of finance for culture, the actual budget allocation for culture dropped from 7.6% to 3.42% between 7th and 8th five-year plans. (The percentage of expenditure is the share of total expenditure on education and not as a share of the entire budget allocation as culture was grouped under the category of education.) An insightful trend in the budget allocation was the change in the proportion of cultural fund share between the centre and the states. While in the 7th plan, the budget allocation for the centre is more than double than that of the states, in the 8th plan the states received a much higher share, almost equitable to that of the centre. In the 9th plan (1997-2002), again an emphasis was laid on the zonal cultural centres to undertake the task of creating a meaningful dialogue between artists from different regions. This plan also formally recognised the need to allocate a higher corpus for state funds to enable their sustenance. To ensure sustenance of artists, the erstwhile schemes like ‘Guru-Shishya Parampara’, were updated to increase the amount of government aid being provided to the artists. It is vital to consider that this plan was spread over two decades – 1990s and the 2000s, and was formulated after 5 years of structural changes. Yet, the need for central government funds and the government aid for the national and artistic endeavours did not diminish. This poses an important question – Is the proposal for private and corporate enterprises to overtake government in promotion and sustenance of culture a possible or a viable option?

The 9th (1997-2002) five year plan overview for the art and culture1

A look at the brochures of the plays being sponsored by the central organisations and the regional and state cultural centres, elucidate the difference in the outlook of the central and regional sponsorship. The funding by the central government was directed towards well-established artists of national imminence and presence. Whereas the zonal, regional and state level undertakings were instrumental in providing assistance to amateur and newly formed theatre groups that were just beginning their operations. This makes an important point in the analysis of the role and positioning of the central and local governments in the political environment of the 90s. This decade was guided by two overarching themes – creation of a national identity enmeshed with a glorified image of India and recognition and support to local aspirations and concerns. The national outlook was the realm of operation of the central government, whereas the state and regional centres gained importance as the instruments of support for the regional and local aspirations situated within an overarching identity of being Indian.

Slide-4The groups and plays being assisted by central institutions. Image 1: ‘Kag Bhagoda’ by Paridhi group with assistance from Sahitya Kala Parishad. Image Courtesy: Anand Gupt Collection/Alkazi Theatre Archives

Image 2: ‘Wah Ab Bhi Pukarta Hai’ by Act One group with assistance from Bhartiya Natya Sangh in association with Sahitya Kala Parishad. Image Courtesy: Anand Gupt Collection/Alkazi Theatre Archives

Slide-5Theatre Festival ‘Rajya Natya Samaroh’ by Uttar Pradesh Sangeet Natak Akademi, 1990. Image Courtesy: Anand Gupt Collection/Alkazi Theatre Archives

Slide-6Asmita- an amateur theatre group performing ‘Final Solutions’ at 4th National festival Jabalpur with assistance from the North Central Cultural Zone, 1997. Image Courtesy: Anand Gupt Collection/Alkazi Theatre Archives

Slide-7Performance of ‘Ek Aur Dronacharya’ by an amateur group under the Regional Theatre Promotion scheme of North Central Cultural Zone, 2000. Image Courtesy: Anand Gupt Collection/Alkazi Theatre Archives

Though the draft of National Policy on culture was formulated in 1992, it never materialised into an actual policy. This period is best understood not by any uniformity or blanket generalisation but emergence of divergent approaches. The debates regarding the form of government action and policy in the cultural sphere to ensure autonomy and artistic independence was inherently linked to the debates on the basic nature of government in transitioning Indian polity. The question of whether performing arts can sustain without government aid remained pertinent.

Notes

1 Union Budget of India archives : https://niti.gov.in/planningcommission.gov.in/docs/plans/planrel/fiveyr/8th/default.htm

2 http://ncf.nic.in/theme/Default/img/NCF_Introduction.pdf

3 https://mealib.nic.in/?2510?000#12

4 https://eparlib.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/57284/1/external_10_09_1995.pdf

5 https://eparlib.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/57376/1/external_11_02_1996.pdf