Shrinjita Biswas

The indexical character of photography, of capturing objective reality in time, enabled the medium to become an integral technological tool for instating the ‘colonial gaze’, creating grounds for imperial ways of looking at, recording, archiving and exhibiting colonized landscapes and events. As visual artefacts, photographs produced within the spectrum of the imperial gaze actively suppressed and invisibilized the complex histories, epistemologies and existential truths of the colonized ‘other/s’, thus perpetuating the ‘grand narrative’ of conquest and extraction. In Potential History (2019), theorist-curator Ariella Azoulay describes this trope of omission – to capture a “presumed” image – as the “petty sovereign” that “commands what sort of things have to be distanced, bracketed, removed, forgotten, suppressed, ignored, overcome, and made irrelevant for the shutter of the camera to function, as well as for a photograph to be taken and its meaning accepted.”[1]The “imperial shutter”[2] thus creates an unbridgeable distance between the end photographic product and that of the processual performativity involved in its making. The processual act includes the participants in and beyond the frame, the expanse of the landscape beyond what is recorded, and discourses in history that remain in the margins as “potential” narratives, either to be recovered and mostly to be erased.

Working with photographs, archival materials and documents from the Alkazi Theatre Archives and the Alkazi Collection of Photography, the exhibition Spectatorship & Scenography in the Archives (Shridharani Gallery, New Delhi, 4-12 February 2023), presented by the Alkazi Foundation for the Arts as part of the India Art Fair, delves into recovering marginalized histories of the South Asian landscape from its potential state of being erased. Showcasing images from the nineteenth century till the present decade, Spectatorship & Scenography brings to prominence the performative labour involved in the making of a photograph – participation, witnessing, process, staging and scenography – thus subverting the violence of the various modes of erasure integral to imperial practices of image-making and archiving. This exhibition extends the politics of “unlearning imperialism”[3] by generating alternative histories of the landscapes of Delhi and Agra, which have remained omitted from state-generated narratives and official archives in colonial as well as in postcolonial times. The exhibition “unmoors”[4] the twin cities from their historical contexts of touristic imaginings and the colonizer’s ethnographic gaze as sites of spectacles of power, and instead re-imagines new histories through narratives of the ordinary, the life of the people and events in relation to the ever-changing landscapes.

Spectatorship & Scenography in the Archives opens with a hand-painted illustration of a rear view of the Taj Mahal [Fig. 1] as presented in a photograph[5] of the late-medieval mausoleum by the colonial doctor-photographer John Murray.[6] Creating a double-folded reimagining of Agra and its people, a camera-stand from the nineteenth century is staged in front of the painting and a turban is placed on the stand. The turban is the symbolic representation of the absented body of the native, who is present in Murray’s photograph, seated distantly. Unlike the touristic representations of the Taj Mahal captured from the front, Murray’s series of photographs, Taj Mahal from the Banks of the Yamuna River (1858-1862) [Fig. 2], documents the mausoleum from several perspectives and capturing mundane human life around the grand architecture. Murray’s photographic engagement with Agra could be observed within the scope of what Nicholas Mirzoeff terms the “visible relation” in his book White Sight (2023) – “an expansive and contradictory mutual experience”[7] between the photographer and the photographed, where the active process of “de-invisibilizing” the ordinary becomes an act of subversion against state-structured imaginings. In contrast to touristic photographs of the Taj Mahal that celebrate the frontal view, many of Murray’s images present the mausoleum from perspectives other than architectural. Collapsing the hierarchical binary of ‘ordinary’ / ‘extraordinary’, Murray’s photographic compositions de-invizibilize the social environment around the Taj Mahal, where the presence of the native, the deglamourized vision of the architecture during different times of the day and the equations of distance and proximity between the photographer, the native onlooker and the architecture perform as renewed agents in re-imagining historical memories of the landscape.

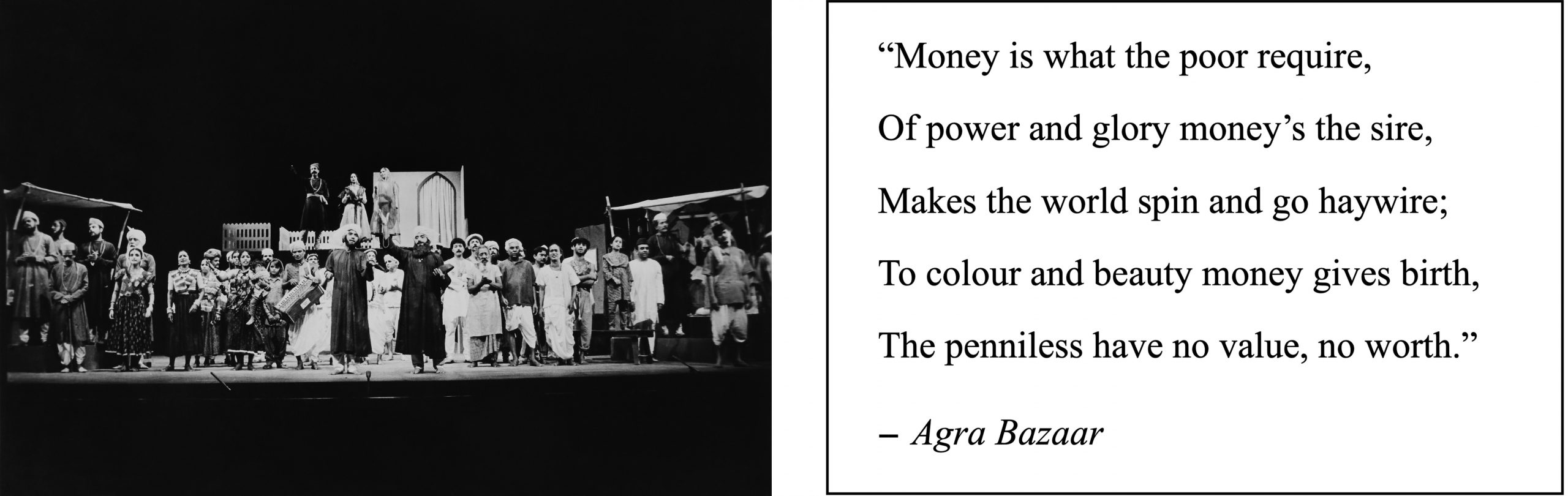

The alternative narrativization of Agra further unfolds in the exhibition through photographs[8] and juxtaposed script excerpts of Habib Tanvir’s play Agra Bazaar, first staged in 1954. Woven around Nazeer Akbarabadi’s poetry, the postcolonial imagination of Agra in Tanvir’s theatre production brings to centre stage the vibrant life of a market on the bank of the Yamuna [Fig. 3]. Understanding theatre as a social document and as an archival site, the collection of photographs of Agra Bazaar pieces together the historical memory and re-imaginings of subaltern life around the river. Photographs from the productions, stretching from 1954 to 1989, illustrate the existential template via the ‘ordinary’ bazaar populated by a lively cast of local ‘characters’ such as laddoo, paan and melon sellers, bear-tamer, burqa-clad women, etc.

The river that remains a passive element/background to the mise-en-scène in the works of Murray and Tanvir becomes an active subject/participant in staged photographs by Kush Kukreja.[9] Titled Yamuna Local Stories, through this devised series of photographs, Kukreja counters the ‘evidentiality’ of images that present a linear character of the cultural memory of Yamuna. He subverts the “popular gaze”, wherein the river is depicted as “froth-filled and polluted,”[10] and instead uses research and survey documents available in open-source archives to offer a radically re-scripted, embodied relationship to the river. Through strategic representation – self-portraits of the ‘photographer as surveyor’ and the river as the ecological stage – Kukreja overturns the act of ‘looking at’ through the politics of enacting ‘to be looked at’ by eliding the figural and the topographical to foreground human complicity through an anthropocene lens [Fig. 4].

The remaining two series of photographs in the exhibition unravel the landscape of Delhi.

The first series showcases photographic works of amateur Parsi practitioner Motivala, chronicling scenes of the 1911 Delhi Durbar that commemorated the coronation of King George V.[11] The official photographic repository of this event navigates the theme of ‘spectacles of power’, where the hierarchical division between the British monarch and the conquered ‘others’ is starkly visible in the performance of colonial power. In contrast, Motivala’s documentation emerges as a visual counter-narrative that strips the event of its pageantry and glamour, as exemplified in Figure 5. Here, a subaltern discourse is generated through long-shot framing that omits the royals and aristocrats and offers an elevated view of the public massed on the periphery of the site, serving as the ‘ordinary’ backdrop to the ‘extraordinary’ choreographed event. The backdrop of the event becomes the central staging ground, and the people present in these photographs gain their subjective agency within the histories of the spectacle by embodying multiple roles – that of the labourer (in the making of the event), the witness, the spectator and the protagonist. Motivala’s series weaves a public memory of the Durbar, resisting the violence of extraction inherent within the economies as well as in the visual regimes of imperial cultures.

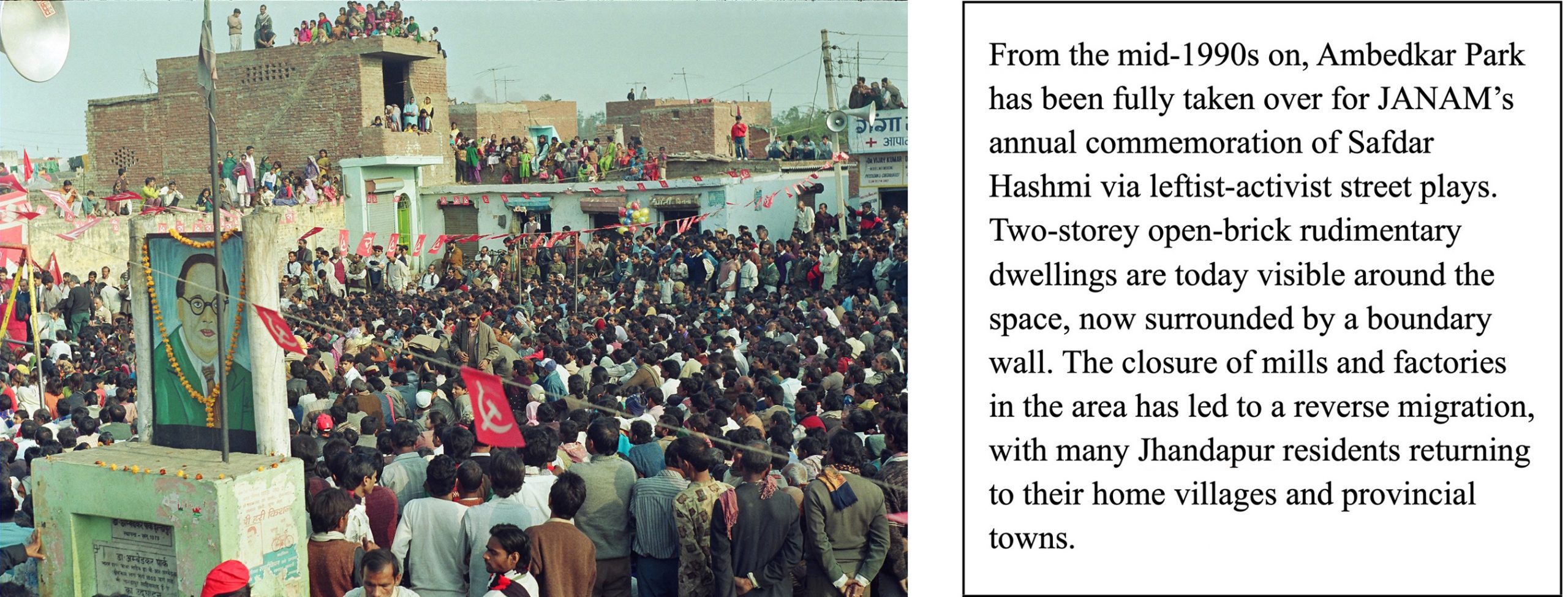

The second series presents the site of Jhandapur, located in an industrial belt across Delhi’s eastern border, through photographs[12] of street productions performed by Delhi-based leftist theatre group Jana Natya Manch (JANAM)[13] at the locality’s Ambedkar Park over a span of thirty-three years. Following the violent attack on the group’s convenor Safdar Hashmi at the site in 1989, Safdar Hashmi Shahadat Divas (‘Safdar Hashmi Martyrdom Day’) is organized annually as a tribute to Hashmi who was killed by political rivals during the performance of Halla Bol (‘Raise Your Voice’). Rather than capturing the performances, these documentary photographs map the fluctuating demographic of spectators, the residents of Jhandapur – migrant labourers, mill and factory workers and their families – who attend JANAM’s performances at the park each year. In Figure 6, two ‘extraordinary’ signifiers – Dr Ambedkar’s garlanded portrait and the Communist flag – instantly politicize the ‘ordinary’, anonymous working-class viewers, suggesting their agency and potential participation in the struggle for social and economic justice.

The last segment in the exhibition is a series of handmade passport-sized portraits by Kishan Chand Hemlani14 who was born in Pakistan in 1940 and started working as a ‘minute camera’ photographer after moving to Ajmer in Rajasthan in 1961. A box-shaped device which was in vogue till the 1990s until the transition towards digital technology, the minute camera was mainly used by practitioners in India to capture ‘identity prints’ of the large numbers of rural and small-town migrant labourers moving to urban centres to earn their living. Much as in the posed studio photographs of the nineteenth century, the subject had to remain still for a minute, ‘performing a pause’, in order to be shot with perfect exposure. Taken in a tent in the pilgrimage town of Pushkar, Hemlani’s photographs from 1966 capture anonymous hippies and pilgrims, villagers, and people wanting a passport image for official documentation. Images of the last-mentioned group are absorbed into the ‘national’ projects of identity formation, and instrumented through administrative regulation of those who are “deemed citizens, exiles or illegal aliens.”[15] Hemlani’s photographs present a paradoxical interface of “identified anonymity”[16] that punctures state-annotated histories and edicts of legibility and illegibility, inclusion and exclusion. His archive here becomes the stage wherein public memory re-enacted in the form of identity prints, recovering the subjects from state-inflicted erasure.

Through its alternative approach to archival practices and its emphasis on performative modes of presentation, Spectatorship & Scenography in the Archives builds a certain form of resilience amidst state-appropriated histories and representations. By staging the anonymous human figure or the crowd – distant or multi-referential, simultaneously present at the periphery and at the centre, both as the spectator and the protagonist – the exhibition generates ‘potential histories’ that trace the marginalized cartography of public memory through the shifting topography of the South Asian landscape. Collectively, these photographs decontextualize themselves from the origin of colonial ‘data’ culture, and instead weave new histories through staging of the dramatic pull between the real and the constructed, between claims and counter-claims, between the ordinary and the extraordinary.

Notes

- Ariella Azoulay, Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism (New York: Verso, 2019), p. 2.

- ibid., p. 3.

- ibid., p. 5.

- Curatorial Note, exhibition text, Spectatorship & Scenography in the Archives (Shridharani Gallery, New Delhi, 4-12 February 2023).

- John Murray (1809-1898), an army doctor assigned to the medical service of the East India Company, took up photography around 1849. He lived and worked in India for forty years, and while stationed near the Taj Mahal became deeply interested in the Mughal architecture of the region, photographing extensively in Agra and other parts of Uttar Pradesh, using the unwieldy equipment then available to produce a body of work unsurpassed in its time. “In the mid-1800s, no simple method of enlarging photographs existed. To make a sizable print, Murray worked with a large-format wooden camera capable of accepting negatives up to 16 by 20 inches. He worked with both glass and waxed-paper negatives; traveling photographers and those in remote places found the waxed-paper negatives particularly useful because the paper did not require immediate development.” https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/person/103KD7

- This image is part of the Alkazi Collection of Photography.

- Nicholas Mirzoeff, ‘Introduction’, White Sight: Visual Politics and Practices of Whiteness (Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2023), p. 14. As Mirzoeff notes elsewhere about “white sight”: “It’s not the way that people who are identified as white see, or have vision – that’s something different. This is a collective enterprise, a systemic making visible… On the one hand, there’s the foundational idea that there is such a thing as white people, who possess something called ‘whiteness.’ This whiteness is not an unchanging or natural category… white sight is always relational – a way of organizing the world so that the invented collective ‘white people’ can create a reality that accords to their sense of the world. And if it doesn’t, they use violence to close the gap between their version of reality and what exists… At another level, white sight is an operating system of what it is to make whiteness and white supremacy, which functions by connecting assumptions, contexts, learned experience, stereotypes, and techniques into a whole. And it has a long history… White sight regulates bodies, land, and the relations between them by means of its capacity to survey colonized space, to claim it, and to place all forms of life under surveillance. I think of white sight not as flat, like a painting, but as deeply layered and sedimented, as in geology where you have stratigraphic layers of rock; or like a Photoshop document, which is composed of multiple layers, some of which you can see and some of which you can’t, but they’re all there. And if you manipulate the document, another part of that layering can become visible. It was important to me to evoke this long history, because otherwise I don’t think we get a sense of the force of the deeply embedded system that we’re trying to contest.” See Natasha Lennard, ‘The General Crisis of Whiteness: A Conversation with Nicholas Mirzoeff’, Los Angeles Review of Books, 1 June 2023; https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/the-general-crisis-of-whiteness-a-conversation-with-nicholas-mirzoeff/

- These photographs are part of the Nagin Tanvir Collection/Alkazi Theatre Archives. Founder of the Naya Theatre Company in Bhopal, Habib Tanvir was pivotal in taking traditional and experimental theatre arts/performance to public urban and rural settings. He was known for his paradigmatic reworking of traditional folk forms through sustained engagement with indigenous communities in the tribal region of Chhattisgarh in Central India.

- Kush Kukreja is the recipient of the Theatre Photography Grant, Alkazi Theatre Archives, 2022.

- Kush Kukreja, Artist Statement, Alkazi Theatre Archives, Alkazi Foundation for the Arts, 2022.

https://alkazifoundation.org/alkazi-theatre-archives-alkazi-foundation-for-the-arts-5/ - Motivala’s photographs of the 1911 Delhi Durbar are part of the Alkazi Collection of Photography.

- These photographs are part of the Jana Natya Manch Collection/Alkazi Theatre Archives. Safdar Hashmi (1954-1989) was noted for radical street theatre, with its dialogic possibilities magnified through adept spatial usage, and through the Brechtian tactic of deliberately reducing the gap between performers and audience. His death stunned, and then galvanized, India’s artist community. Hundreds of people stood vigil outside the hospital, and thousands accompanied his funeral procession. Two days after Hashmi’s cremation, his wife Moloyshree, herself a theatre actor, returned to the same location with colleagues and a large crowd of supporters, and the troupe performed the same play in full. The artist collective Safdar Hashmi Memorial Trust (SAHMAT) was founded in Hashmi’s memory, with a mission to generate public discourses on art as a regular socio-political practice, and on the function of art as a platform for the enunciation of dissent when democratic rights are threatened. To this day, for practitioners across the arts spectrum Hashmi remains a potent symbol of passionate conviction and anti-authoritarian courage.

- Jana Natya Manch (JANAM) was founded in 1973 by a group of radical theatre activists from Delhi. Inspired by the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA), JANAM’s street theatre is themed around women’s rights, trade unions/workers’ rights, cost of living, unemployment, and labour exploitation, as well as communalism, elections, education systems and economic policies. Some of its important productions are Machine (1978), Aurat (1979), DTC Ki Dhandhli (1979), Raja Ka Baja (1980), Mai Diwas Ki Kahani (1986), Halla Bol! (1989), Hatyare (1978), Yeh Dil Mange More, Guruji! (2002) and Honda Ka Gunda (2005).

- The Minute Camera Archive is part of the Alkazi Collection of Photography. For a detailed account, see Sean Foley (text) and Lukas Birk (photography/design), Indian Minute Camera Photographers (Fraglich Publishing and the Alkazi Collection of Photography, 2021); https://alkazifoundation.org/indian-minute-camera-photographers/

- Rahaab Allana and Sean Foley, exhibition text, Ephemeral: New Futures for Passing Images, Serendipity Arts Festival, Goa (2018).

- ibid.

Shrinjita Biswas is a doctoral student/Graduate Fellow in Interdisciplinary Theatre Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her research focuses on gender and performance, political theatre, South Asian studies and Indian performance cultures, and feminist discourses in theater, performance and new media. Her artistic pursuit lies at the intersections of performance, film, sound and photography. Shrinjita has worked as Senior Research Assistant at the Alkazi Theatre Archives, Alkazi Foundation for the Arts, New Delhi. Her writings have been published on Sahapedia, Critical Collective, UPAJ India, Take on Art, and other forums, and her works have featured in the Asian Women’s Film Festival (2019) and the Sahapedia Film Fest (2020).

Shrinjita Biswas is a doctoral student/Graduate Fellow in Interdisciplinary Theatre Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her research focuses on gender and performance, political theatre, South Asian studies and Indian performance cultures, and feminist discourses in theater, performance and new media. Her artistic pursuit lies at the intersections of performance, film, sound and photography. Shrinjita has worked as Senior Research Assistant at the Alkazi Theatre Archives, Alkazi Foundation for the Arts, New Delhi. Her writings have been published on Sahapedia, Critical Collective, UPAJ India, Take on Art, and other forums, and her works have featured in the Asian Women’s Film Festival (2019) and the Sahapedia Film Fest (2020).