by Anita Khemka & Imran Kokiloo

Text by Anita Khemka

Shared Solitude was born out of a literal and forced isolation as a result of a family emergency coinciding with the very unplanned and brutal lockdown of March 2020. My partner, Imran was left alone with our two daughters while I had to take my mother for an emergency surgery which was followed by a two-week quarantine period. This spurred him to contemplate on questions pertaining to the concept of a family, what it is built on, what it thrives on, and what it is limited by; how one comes together in this shared space and navigates between what is truly individual and what becomes familial. With this idea as the basis, we discussed the possibility of making family portraits.

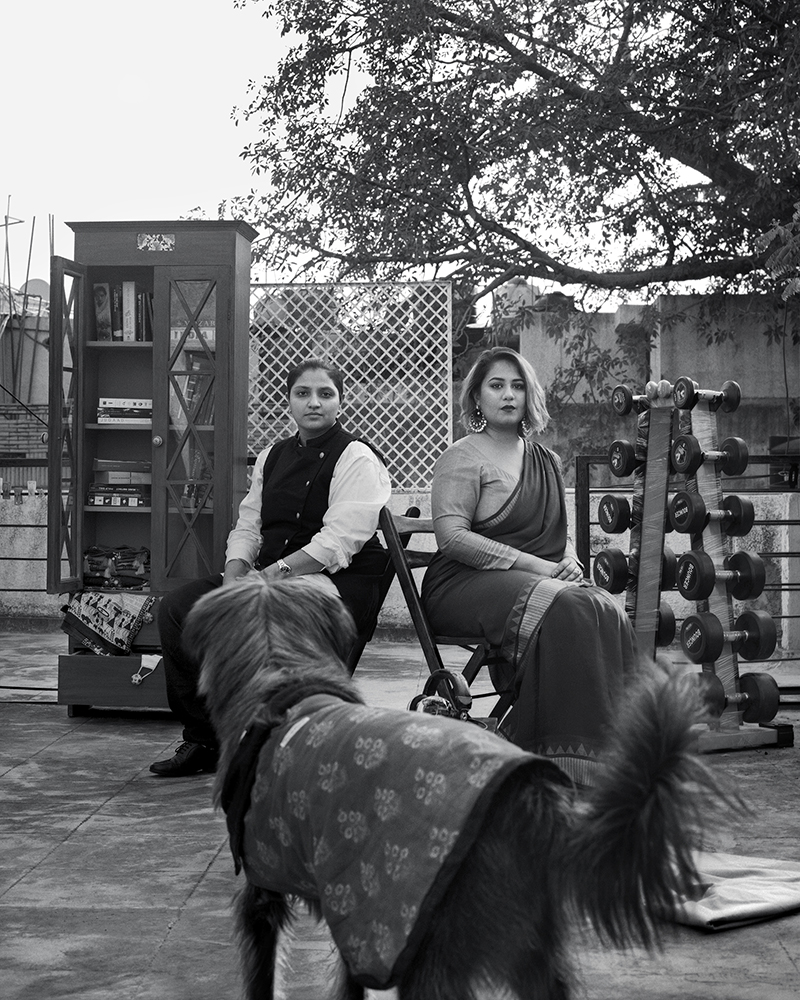

It was clear to us from the beginning that the portraits had to be made in an outside space, a constraint given the safety protocol for the COVID-19 outbreak. As our focus was the family portrait that would include its members and their possessions, we saw people bringing things out of storage to sit for their photograph. In a way, it is like what Ishita, a sitter has recorded for us and I quote, “I have realized that specific relationships, having the time to read, be with dogs, and having enough meaningful work in the day is enough for me – this is all I would like to keep in my life.” Similarly, it seems that the families chose to bring the most defining objects of their family as their impressions of belief, memory, nostalgia, and loss. This project thus set out to excavate memory, the joyous and painful, and confronts the universal dilemma of ownership, possession and letting go.

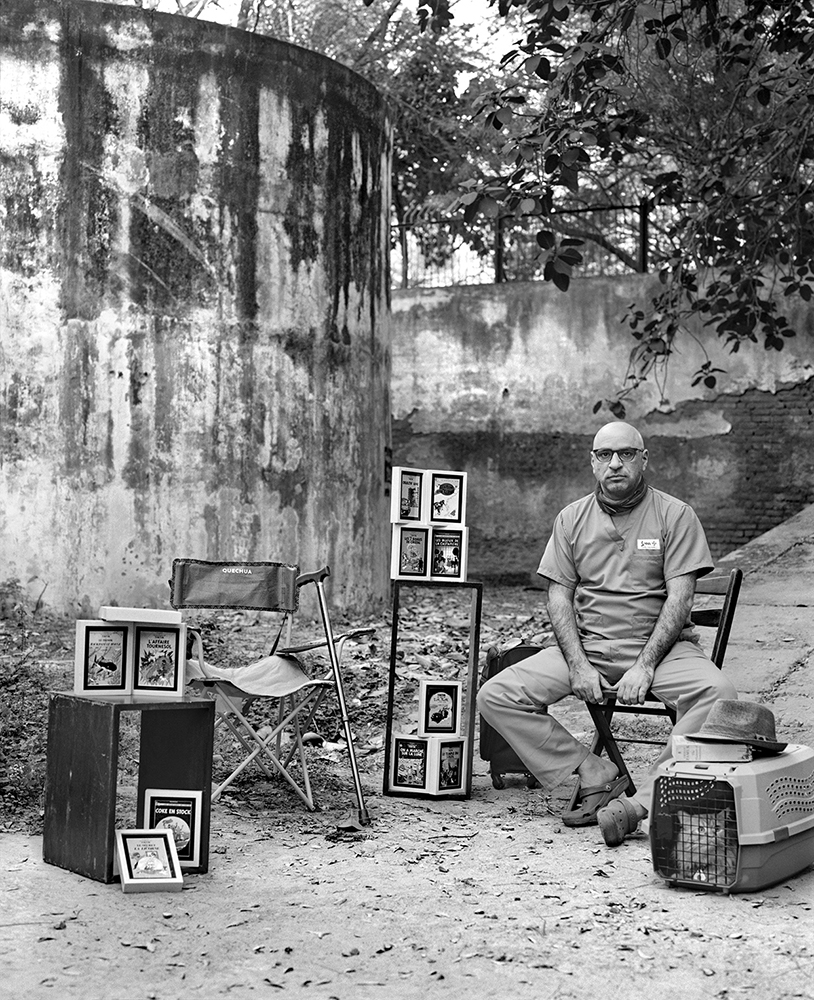

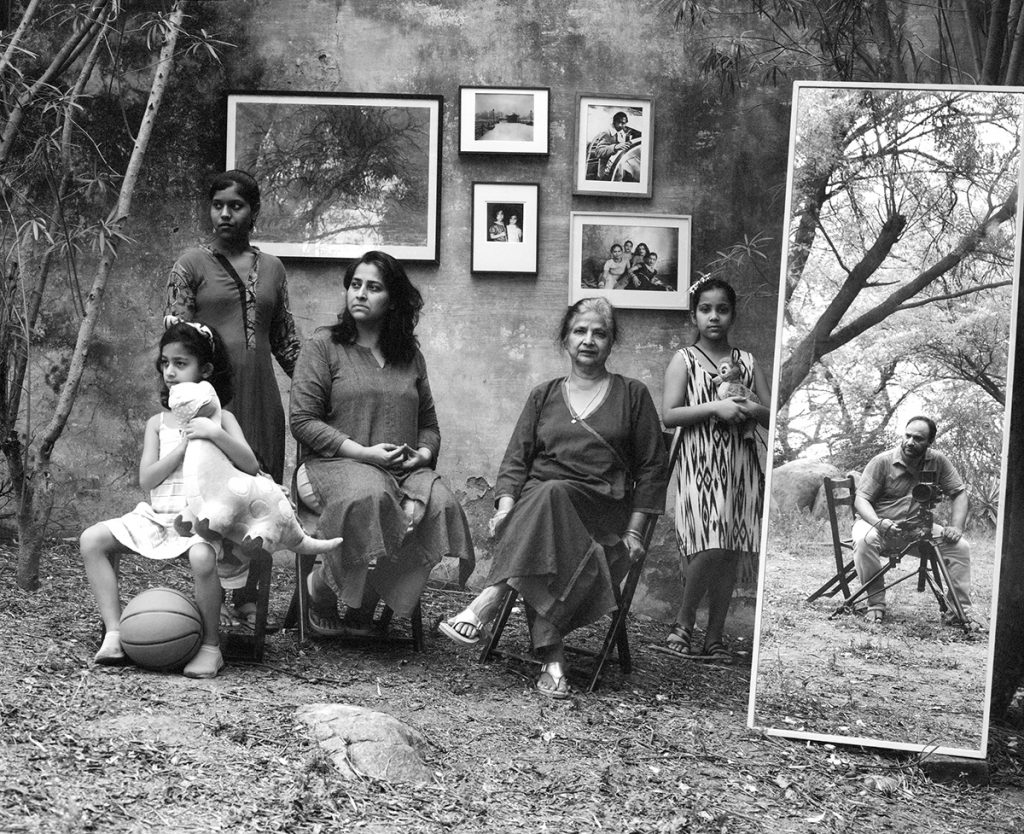

The early images that Imran and I made were in our middle class neighbourhood. We chose the various local parks as a backdrop for the portraits which brought not only our sitters, but us as well, out of our comfort zones. The open-air studio also removed us from the convention of a studio backdrop and the adornments that come along with it, an aesthetic frame of reference imposed by the photographer traditionally. A couple of wooden chairs and boxes were a constant in all the portraits and the challenge now was to create a different setting for each family. Also, to construct a personalized setting that would make the sitters comfortable and feel at ‘home’ was critical. Nidheesh, one of our first sitters said, “There is something very ceremonial about getting a portrait done, even while living under lockdown when life is slow-paced, reflective of a certain unease of being with our own selves, living in shared solitude.” With each portrait, we saw this ceremony being played out – the formality of walking into the park with personal memorabilia and the laying out of these projections of memories and experiences; the silences in posing together, living a most private moment very far from others sitting next to us, while waiting for the photograph to be made.

— Ayesha Misra

The belongings from the homes were clearly out of place in the open space of the parks, yet the proximity and placement of these objects with the sitters created a subliminal relationship between them. They were out of place, yet not so because of the intrinsic relationship they shared with the family. Toys are seen scattered in one setting and neatly arranged in another, frames of Tintin covers crowd another sitter, a bridge table, a wall clock, books – all narrated stories of bonds created or the ones that were being held tight through the projection of memories associated with them. The wheelchair in one of the photographs was of the missing father, who has been a political prisoner for several years now, during which the absent father resides in memories of short furloughs he gets due to his declining health. The line which separates this painful and protracted absence from being deceased is the hope for future memories that we can afford ourselves.

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.”

– Alfred Lord Tennyson

To not yield – that has been the guiding sentiment and also the antidote as well as elixir to triumph over each day over the past year. All that and a bag full of promises, some fulfilled and others yet to dawn. My mother’s empty chair, her walking stick (her presence while she travels), my friend’s feline, a load of Tin Tin’s, the scrubs I have on, serve to fuel the “why, that can bear anyhow.” — Junaid Shafi

For my own family portrait, I was saving a particular spot as the wall seemed perfect. My father in the photograph – young and handsome, the way I like to remember him, which has been by my bedside since 2003. The photograph with Laxmi and her chelas, not only representing our committed relationship but also the years of my struggle with homosexuality since I was twelve and the conflict seeing people close to me leading dual lives. It further speaks for my dependency on photography to deal with skeletons in hiding and issues that one is continually confronted with in life. For the girls, it was their Bambi and Dino (who is wearing a mask) and Prema didi, whom they wanted to include in the portrait. The Piet Mondrian finds its way as a memory of a serendipitous encounter with its original at a museum in The Hague.

I’d like to end by quoting Ushinor, one of our sitters “the result of this portrait shoot will either be a personal memory of a very stressful time with no end in sight, or become someone else’s insight into the beginning of the end.”

Anita Khemka’s photographic practice of twenty five years has focused on gender, sexuality and identity. She is also an educator and currently works for The MurthyNAYAK Foundation as a researcher. She is represented by PHOTOINK and Iives in Nainital, India.