In 2017, the renowned camera company, Kodak, announced the launch of a new magazine, catered to those with an interest in “art, film and analog culture”, called Kodachrome. For a company whose name has been synonymous with photography, right from its founding in 1892, the decision to branch out into a print magazine was particularly interesting. According to its editor, Joshua Coon, who sees this moment as a revival of the analogous era, “…the mag is now an important linchpin in Kodak’s content marketing strategy. It certainly helps build the brand and gives us a vehicle to showcase our print technology. But it has also become an important consumer product.”

Images Courtesy: archive.org

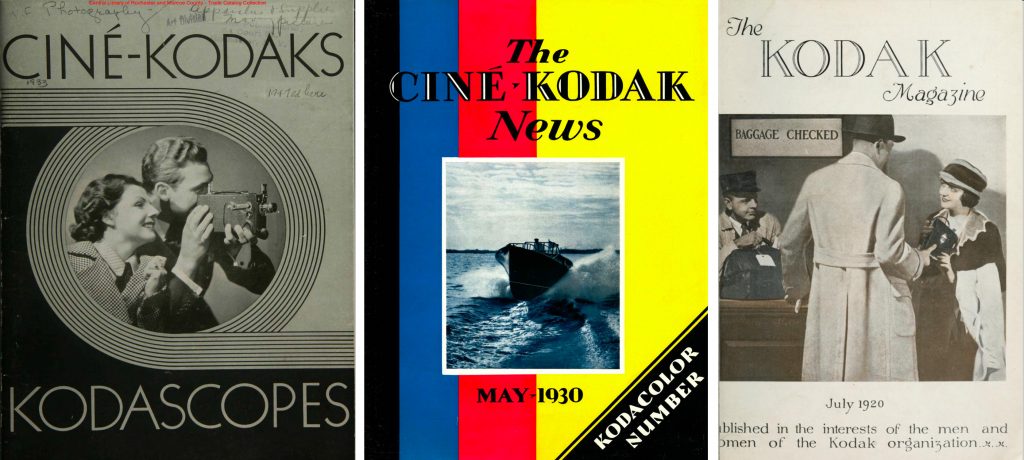

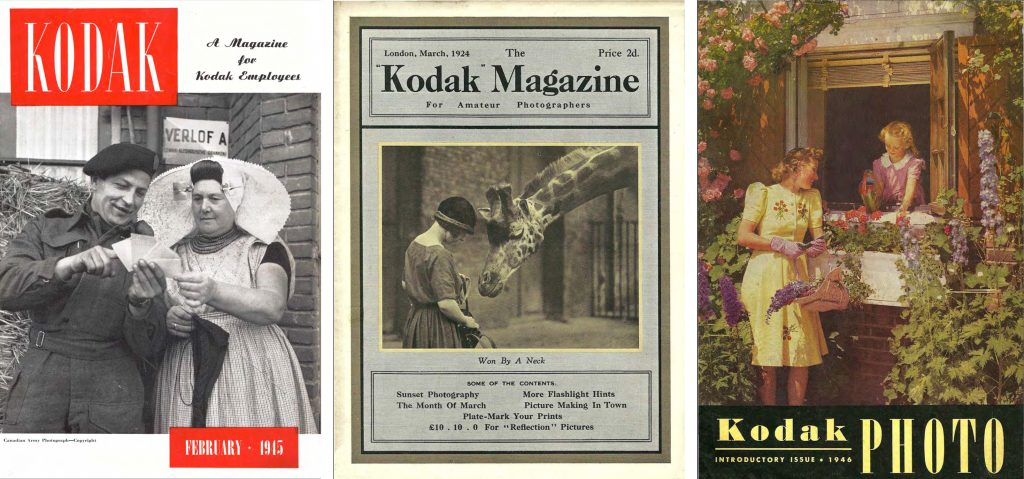

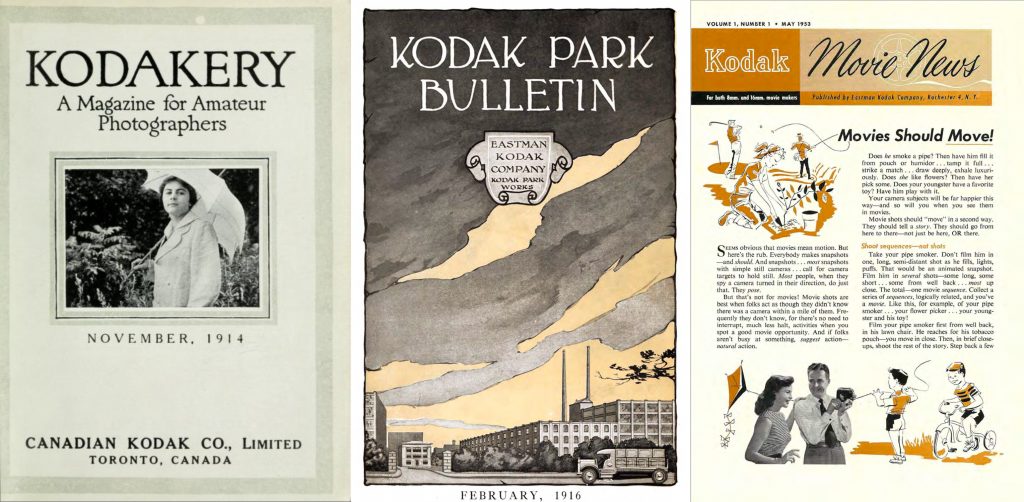

Kodak’s relationship to print has been a long one and varied one. From their inception, they had had a committed relationship to print through a variety of print forms for a multitude of audiences—for example, Kodakery, a newspapers for Kodak employees, Studio Light, a magazine of information for the professional, Photo Spotlight, a magazine for professional photographers, The Kodak Magazine, magazines for amateur photographers, Kodak, a magazine for Kodak employees, Cine Kodaks, a magazine for home movie makers, Kodak Movie News, a newsletter for home movie makers, and numerous other catalogs, magazines and newsletters. Famously, for the different regions that Kodak had its offices in, they produced separate magazines with regional and locally relevant information.

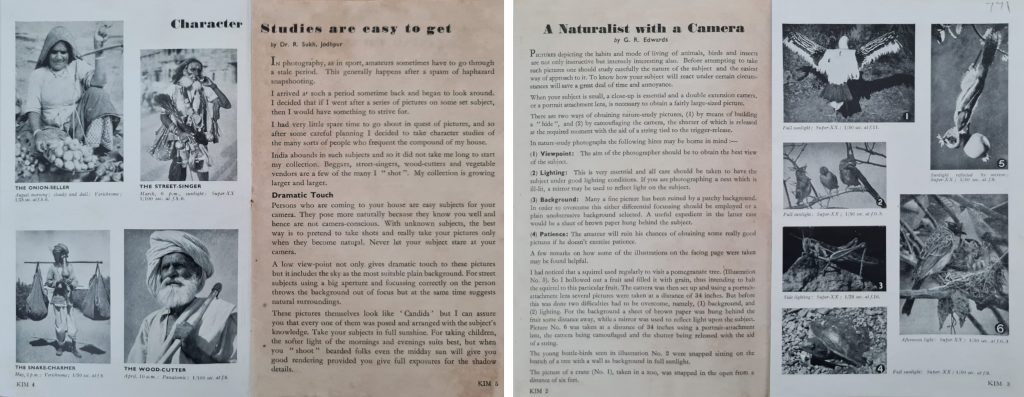

In my constant search for new material dedicated to photography, we recently acquired a copy of a 1943 issue of the Kodak Indian Magazine (KIM, as it was commonly known), a magazine published by the J Walter Thompson Company, on behalf of Kodak Limited in Bombay, possibly starting around the 1940s. One of the first observations about this publication is its compact size. Measuring 7 x 4.6 inches, and no more than 20 pages, the magazine at first resembles more of a manual, than a popular magazine. And unlike other magazines, with no editorial notes, KIM opens immediately with an article titled “A Naturalist with a Camera by G R Edwards”. Yet another feature of the magazine, quite notably, is the inclusion of technical specifications of each image, including the time of capture, type of film and camera settings. The rest of the publication also consists of similar articles, focussing on how to produce “good” pictures; in this case, fixed ideas of non-blurred, in-focus shots with minimal background disturbance; ranging from portraiture to nature photography. The issue also carries results of the KIM photography competition on the theme ‘Festivals’, in which T. Kasinath, who would go on to be a prominent photojournalist, was recognised as a winner. Renowned photographer G. Thomas, also contributes to the issue with an advice column for amateur photographers on how to make their images better. “So disappointing were the entries for the competition this time that the judges were frankly incredulous. …One reason maybe the inability of amateur photographers to obtain as much film as they desire. Now more than ever before is the time you must economise on films by taking only those pictures that are absolutely worthwhile.” Observations such as these made in the magazine, attest to a culture of amateur photography that the magazine was growing parallelly to as well as closely tracking.

At this point, Kodak was also providing a lot of film and camera material towards war efforts which had caused a scarcity of material for commercial use. In an article titled, Finding Family in The Times of India’s Mid-Century Kodak Ads, scholar Jennifer Orpana, writes about how the advertisements from these times also highlight the scarcity, but didnt let it deter their marketing efforts. Consumers were encouraged to “make the most of” their film, pictures and other photographic material, but also continue their hobbies till the war ended. An article from KIM also provides tips to amateur photographers on how they could economise their film and also perfect their photographs so as to not waste film.

The issue only relies on indirect forms of advertising, for example, the competition rules state that though photographers might use any camera of their choice but photos might only be taken on Kodak negative material and prints must only be made on “Velox” or Kodak Bromide Paper. But the only advertisement in the issue is also an example that both highlights the company’s contributions to war as well as encourages customers to “wisely” continue their practice of photography.

Other photographic companies such as Agfa and Ansco, were also known to have had dedicated magazines which were widely popular. According to sources, the Agfa Photo Gallery magazine, “…though free, was so much in demand that amateurs often were disappointed to find copies sold out at photo dealers. To keep up with the tremendous demand, Agfa India Ltd announced that readers could have all 12 issues each year by sending the publisher an amount of Re. 1 to cover postage charges.”

Thus with the launch of their new magazine, it is evident that magazine culture and the dedicated audience base built through it has been a popular marketing strategy that Kodak has long relied upon. It is to be seen how the transformation of photography, largely into a digital medium, gets translated into the medium of print.