In collaboration with Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (IGNCA)

“Like a wood fire in a room, photographs – especially those

of people, of distant landscapes and faraway cities,

of the vanished past – are incitements to reverie.”

-Susan Sontag

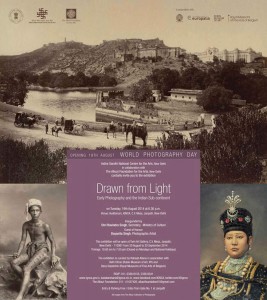

Drawn exclusively from the Alkazi Collection of Photography, this exhibition traversed the history of architectural, landscape and portrait photography in the Indian subcontinent, from 1850 till 1910. The photographs, delineating the perceptions and constructions of the subcontinent through the eyes of the “outsider”, conjured images of an exotic world and its peoples.

landscape and portrait photography in the Indian subcontinent, from 1850 till 1910. The photographs, delineating the perceptions and constructions of the subcontinent through the eyes of the “outsider”, conjured images of an exotic world and its peoples.

With the coming of photography to India in 1840, the erstwhile employment of water-colours and drawings for the documentation of new territories was replaced by the more economical and “objective” means of visual appropriation. The exhibition, displaying the architectural and topographical views captured by the lenses of Samuel Bourne, John Murray, Alexander Greenlaw and Lala Deen Dayal, outlined a visual dynasty of the picturesque tradition in the pictorial vocabularies of the period – from Murray’s repeated shots of the Taj Mahal in pursuit of the ideal composition, Bourne’s aesthetically exquisite landscapes to Greenlaw’s intriguing calotypes of the Vijaynagara site. Perhaps no Indian photographer achieved the commercial success of Deen Dayal who, poised between the two worlds of Anglo-India and princely-India, creating some of the finest architectural photographic records.

The secondary positions occupied by human-subjects in these geographical narratives were reversed in the anthropometric studies and portrait photography. Simply by physically turning the camera’s horizontal position to a vertical one, photographers undertook detailed studies of the “natives”. By the 1860s, there was an increasing interest in the ethnographical documentation of the various tribes and sects. The epitome of a ‘colonial science’, these photographs recorded people across the communal spectrum, categorizing them according to their occupations. The exhibition hosted William Johnson’s prints from one of the earliest ethnographic albums in the colonial world – the Oriental Races and Tribes. Most of these images were photo-montages set against photographic backdrops.

Similar to the proliferation of the picturesque in landscape photography, there appeared visual and conceptual continuities in portrait photography with the suffusion of Rajput and Mughal aesthetics in the new technique. The exhibition offered a survey of vintage images from India, Ceylon, Burma and Nepal, with contributions from a myriad of photographers – Felice Beato, Johnston and Hoffman, Herogg and Higgins, Matzene, Skeen, Shapur Bhedwar, Hurrychand Chintamon and Abbas Ali. Containing painted photographs from India and Nepal, the exhibition also incorporated albumen prints, gelatin silver prints, glass plate negatives and wax paper negatives amongst others.

With the increasing popularity of photography, commercial photographic studios soon sprouted in Madras, Calcutta and Bombay. This popularity was accompanied by a recognition of photographs as souvenirs, and the mass-circulation and democratization of the hitherto enclosed medium. This cartomania, a means of globalizing the image, was made possible by carte-de-visite, cabinet cards, stereographs, and postcards, some of which were also showcased in this exhibition.

Drawn from Light was thus an attempt to illustrate the panoramic discourses at work in the 2nd half of the nineteenth century and early twentieth century through its extensive collection of the variegated visions of the colonial subcontinent.