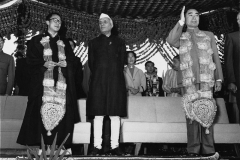

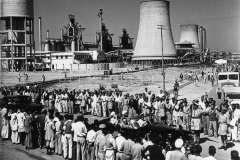

IN INDEPENDENT INDIA, the new government required press photographers to document the rituals of their arrival. These included oath-taking ceremonies, inaugurations and a variety of public functions. Attention was given to the documentation of new steel plants, dams and industries along with national and cultural rituals. Nehru can be seen posing with Republic Day performers as the pageant showcases its ‘museum’ of tribal citizens. These images sought to embody the idea of ‘Unity in Diversity’.

Among the many architects of newly independent India, Homai Vyarawalla’s photographs were dominated by Jawaharlal Nehru. Despite being one of the most photographed men in history, Mahatma Gandhi hated the flash of the camera. On the other hand, Nehru was camera-friendly and perhaps Vyarawalla’s most loved subject. He liked performing for the camera and she took some of his most memorable photographs. In these images, India’s first Prime Minister appears playful and expressive. At a time when leaders were not cordoned off by security personnel and photographers were rarely intrusive, Homai Vyarawalla enjoyed the complete trust of her subjects. They unhesitatingly allowed her to photograph them not just in public but also during private moments.

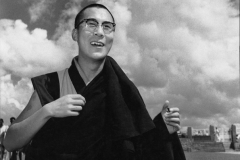

As India forged International alliances, world leaders and important dignitaries visited the country in the first two decades after independence. In 1959, the Dalai Lama sought refuge in the country. By 1962, the clouds of war had gathered, first with China and then Pakistan. Ironically, the end of every war was marked by the death of a Prime Minister. Homai’s camera would document the funerals of both Jawaharlal Nehru and Lal Bahadur Shastri. As the Nehruvian era came to a close, many hopes and expectations remained unfulfilled. By then, Homai Vyarawalla had decided to give up photography.

By Sabeena Gadihoke