Reading Through Theatre Ephemera: Mapping the Post-independence Cultural Sphere in India

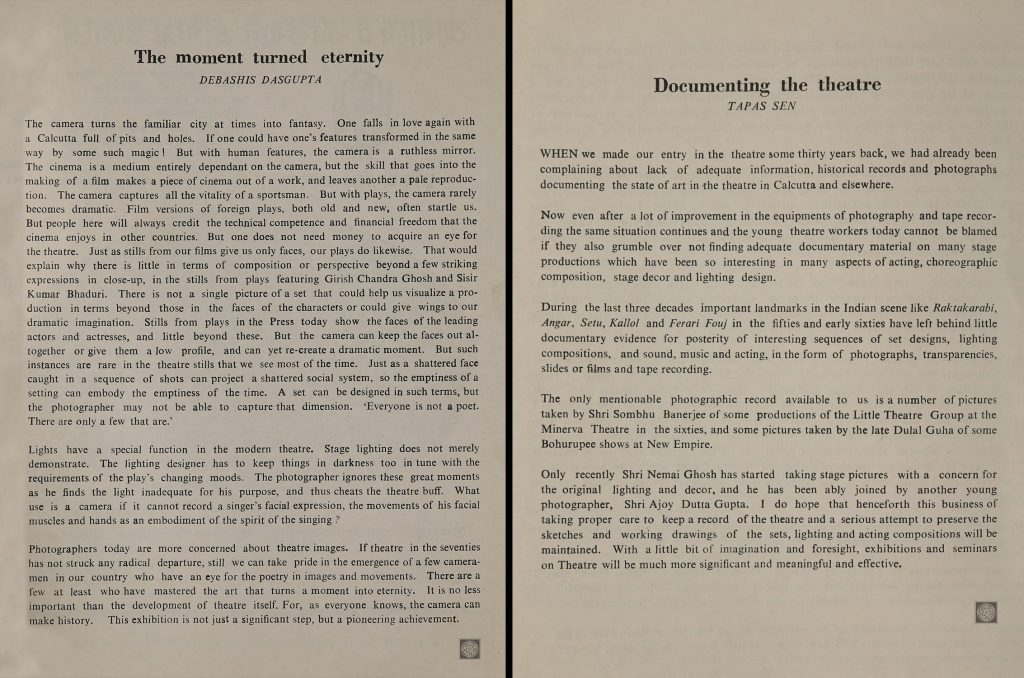

Through the series, Notes from the Archive – Print & Theatre, the Alkazi Theatre Archives explored a multilingual archive from post-independence period in India to illuminate the exchanges, as well as interrelationships between the medium of theatre and different modes of print culture. The Alkazi Theatre Archives houses the Anand Gupt Collection, consisting of newspaper clippings (1965-2010s), production brochures and leaflets, photographs, magazines, journals and news bulletins (1950s-2010s) published in English as well as regional Indian languages chronicling the course of theatre in India. By unearthing such a diverse theatre archive, we touched upon the themes of theatre’s sustainability and its economy, debates surrounding censorship, function of theatre in the society it inhabits, circulation of theatre ephemera, to name a few. Archives serve as repositories of the past, which may go undocumented in the conventional histories. Archival materials are not only essential in mapping the history of theatre in India, but also for preserving the essence of a democratic state by documenting personal as well as collective cultural acts of its citizens. Thus, the archive projects an amalgamation of facts, anecdotes, fictions, myths, and histories, to retell and re-interpret moments in the past through multi-layered narratives. Through cross-cultural as well as interdisciplinary readings, the theatre archives emerge as social documents as well as a site of performance-making. Otherwise undocumented in the national and state archives, the theatre archive aids in bringing forth the voices of the marginalized and those on the periphery producing alternative discourses on theatre and reconstructing social and political histories.

Theatre and vernacular print culture emerged hand in hand during the colonial period in India and became highly instrumental in propagating the anti-imperial struggle as well as bringing social, cultural, political and gender issues to the fore. By the mid twentieth century, theatre news was circulated not only in the national sphere , but also internationally. Aparna Dharwadkar in A Poetics of Modernity stresses on the importance of ‘the retrieval of a multilingual archive’ in opposition to a ‘national language’ archive, to arrive at a comprehensive understanding of the constructedness of ‘Indian’ identity and modernity through theatre theory. Her work addresses this lacunae in Indian theatre theory by bringing together English translations of a select few theoretical arguments and standpoints in regional languages from the modern period to ‘reflect significantly on the form and institution of theatre, make explicit what is implicit in practice, and/or attempt to shape practice through prescriptive and polemical strategies’.

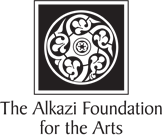

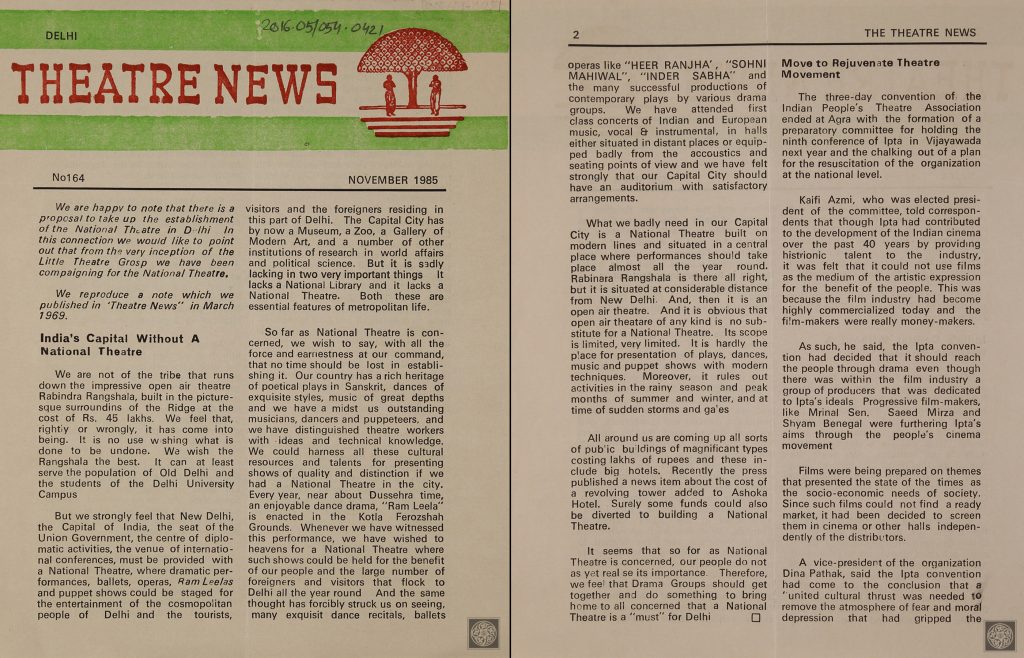

While working on the ongoing Print & Theatre research project, the issue of a ‘national’ theatre repeatedly showed up through the post-independence ephemera with regards to its form, genre, venue and the content. Conferences and seminars were held by both state and private organizations debating on the need and nature of national theatre/s. For instance, a 1978 Economic Times report by Shanta Serbjeet Singh reviews the two day seminar organized by Shriram Centre for Art and Culture, Delhi to discuss the issue of the need for a ‘national theatre’ in India where it was recommended that given the multiplicity of languages and genres in India, multiple national theatres must be instituted in each state with assigned repertory companies. Such discussions on the nature and epistemes of theatre in independent India can be seen in a number of print ephemera including Kalavaarta (Desi Dimag Ki Jarurat – Prabhat Kumar Tripathi, 1981), Theatre News (India’s Capital Without a National Theatre, November 1985), Financial Express newspaper article (1978) titled ‘Bogus concern for a national theatre’.

Print modes in different formats and languages catered to a variety of audiences delivering:

- national, international, regional theatre news,

- drama, play and production reviews,

- festival and conference schedules and reports,

- book reviews,

- translations of dramas,

- debates and discussions on contemporary theatre,

- interviews,

- dialogues between the writers and readers through letters to the editors,

- opinion articles,

- columns on theatre history, etc.

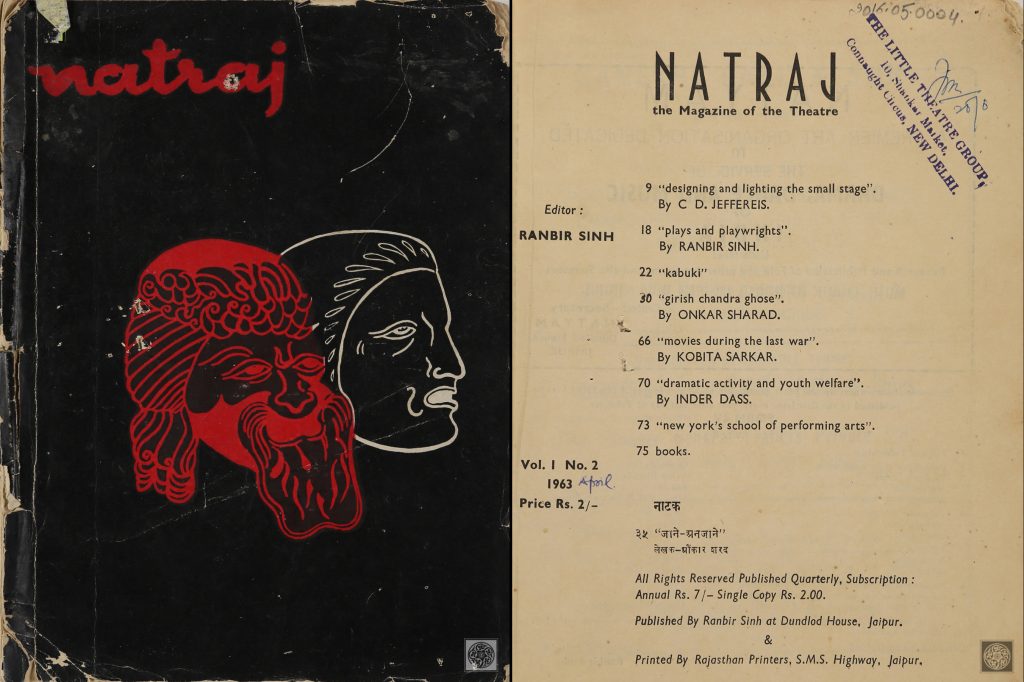

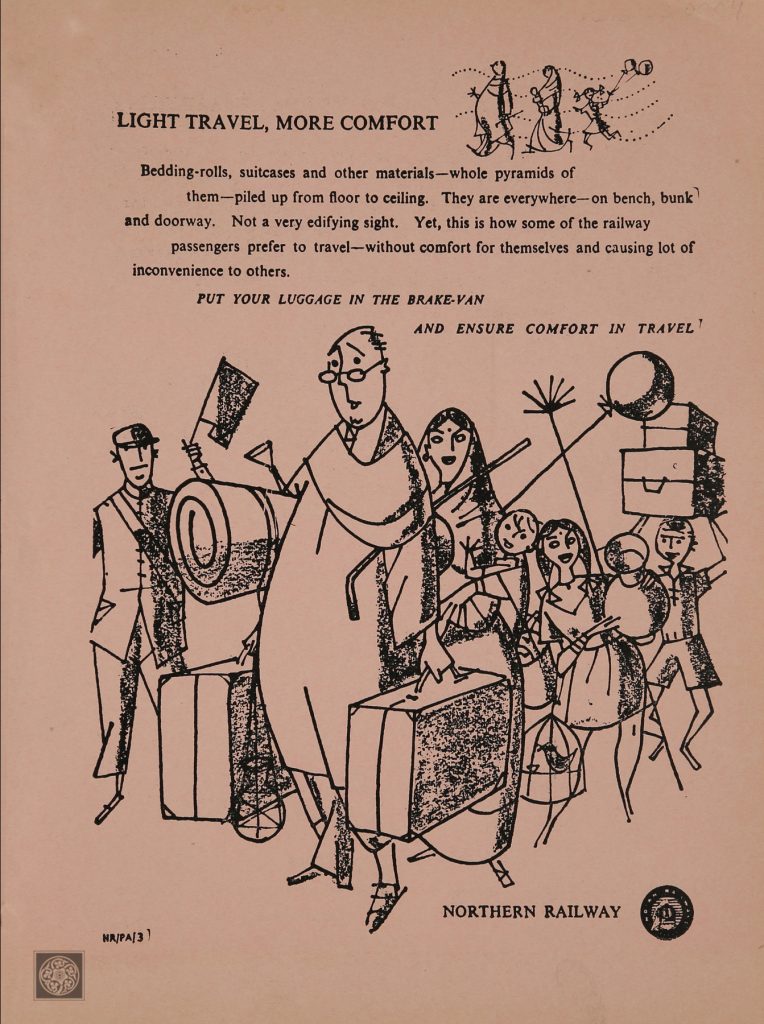

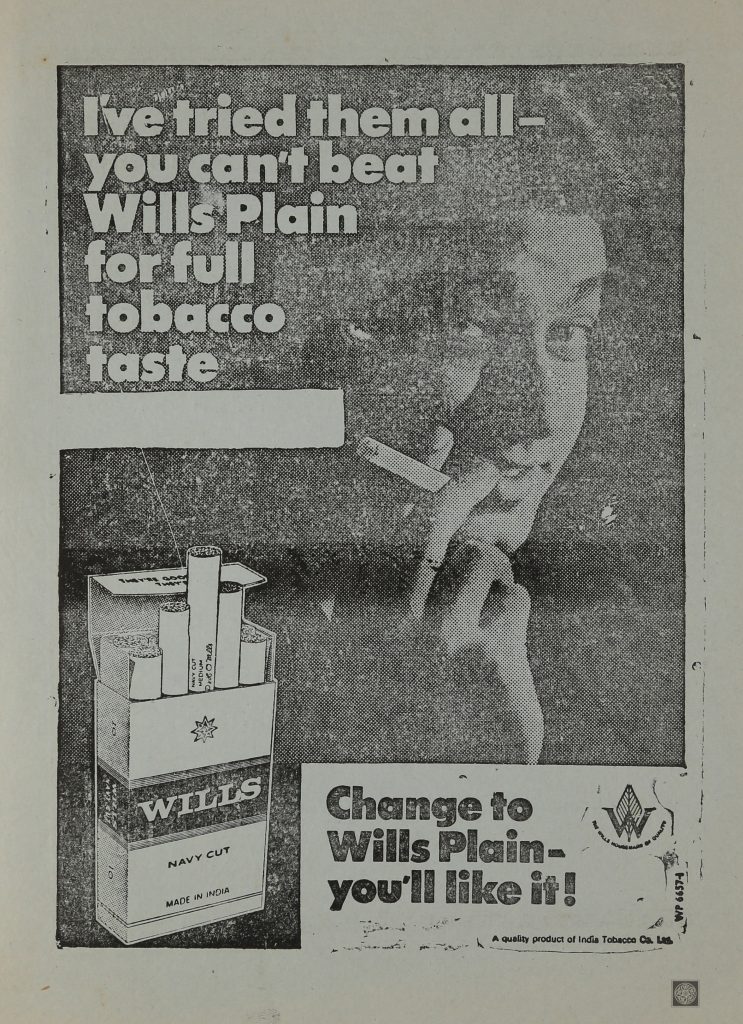

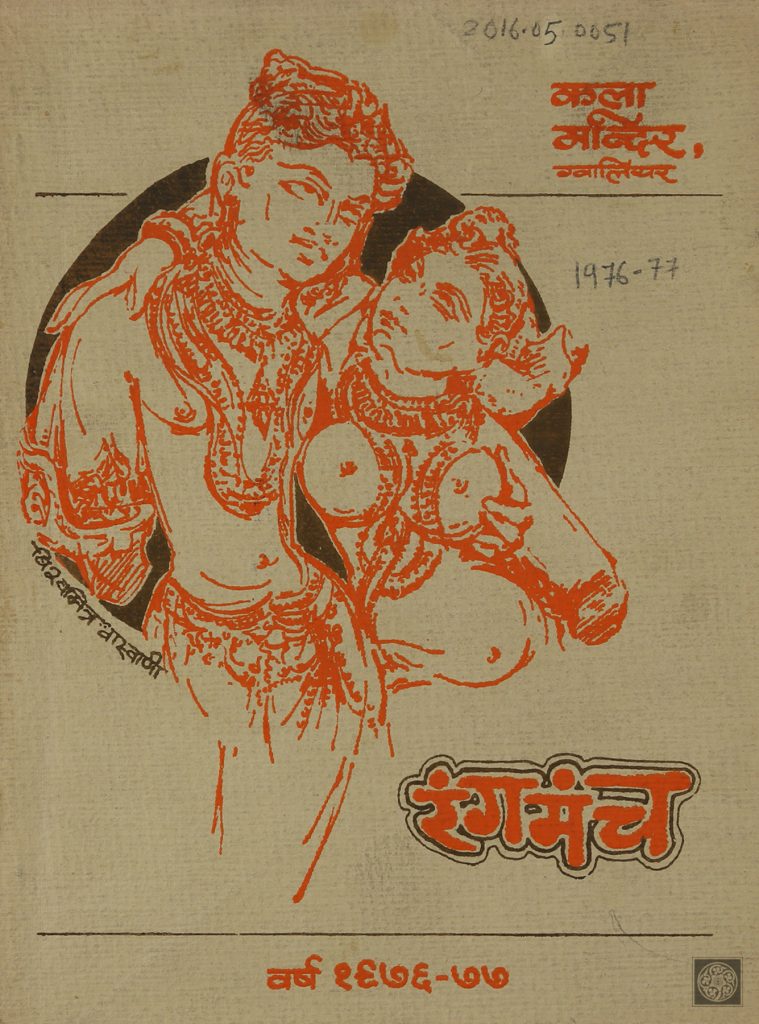

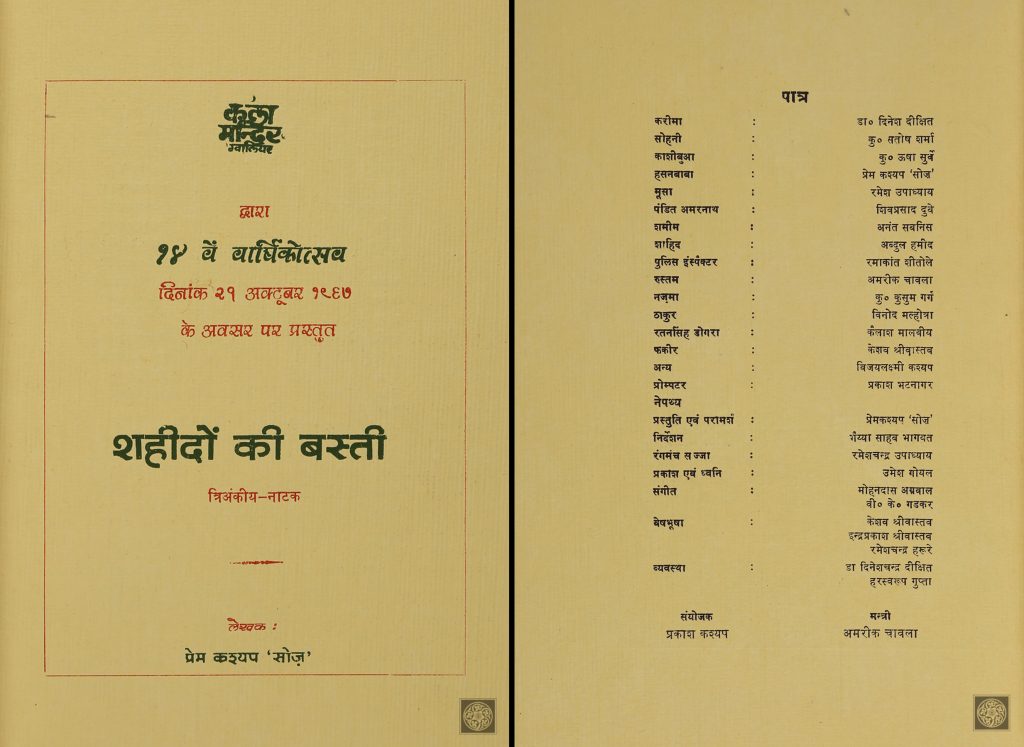

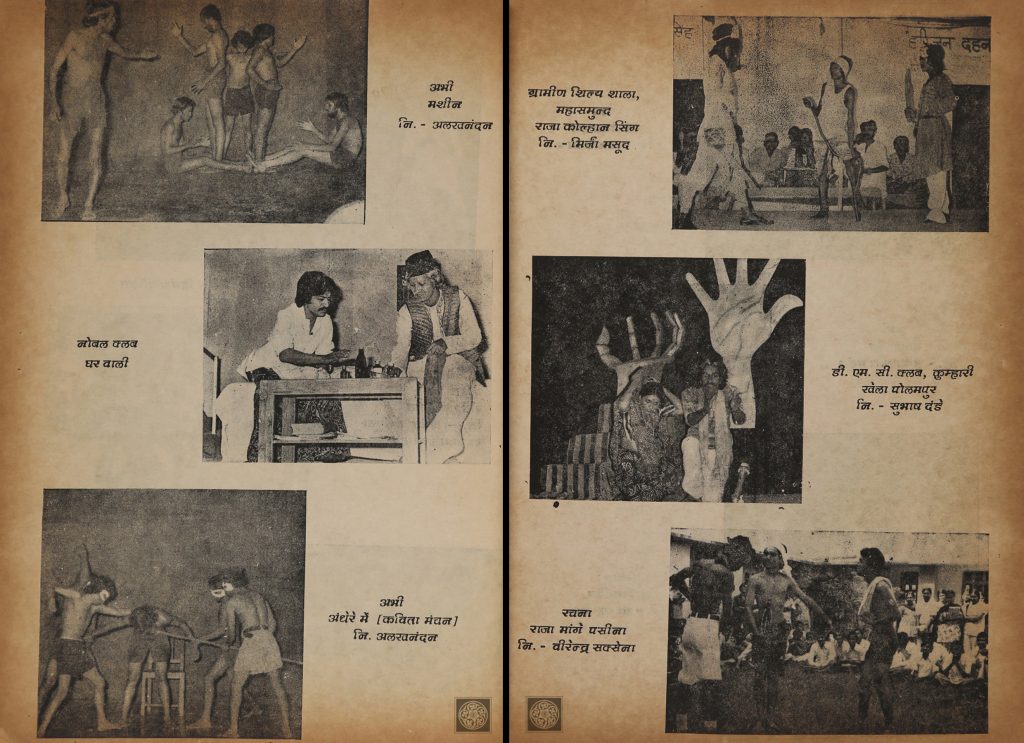

Unlike the colonial period when theatre ephemera was produced by theatre companies and groups theatre ephemera were now also produced by state owned and sponsored institutions like the Sangeet Natak Akademi, Bharatiya Natya Sangha, Zonal Cultural Centres and regional culture departments. Theatre groups and independent organizations like Natrang Pratishthan’s Natrang (Delhi, started in January, 1965), Sankalp theatre group’s Bharat Shastra (Mumbai, started in September 1979), Little Theatre Group’s Theatre News (Delhi, started in early 1970s), Anand Gupt’s Abhinay (Delhi, started in 1976), etc. added to the private discourse of theatre print culture. The earliest magazines in the Anand Gupt Collection include Bharatiya Natya Sangh’s theatre arts journal called Natya including special issues on International Theatre (1958), Theatre Architecture (1959-60) and Tagore Issue (1961). Apart from a few English language theatre magazines like Natya which reported on international theatre happenings and regional theatre magazines like Kala Mandir, Gwalior’s Rangmanch, most magazines received very few advertisements and were short-lived. To survive and sustain the publication of print ephemera on theatre, magazines like Bharat Shastra (September, 1978) appealed to its readers and stakeholders for financial aid by inviting advertisers and subscribers. Despite financial and economic restraints, magazines like Natarang published by Natarang Pratishthan, Delhi and edited by Nemichandra Jain continue to publish the quarterly till date.

Post-independence, India saw a boom in the publication of theatre magazines in English and regional languages like Hindi, Marathi, Konkani, Punjabi, Bengali, to name a few. Although it is difficult to grasp the accurate reach and popularity of each of these magazines, the number of advertisements, quality of paper, use of colors, photographs, illustrations and subscription flyers serve as an entry point into examining the target audiences and circulation of these magazines. With innovative ways of journalism, like Abhinay published in the form of an inland letter journal, a four-fold single page newsletter of Indian Society for Arts and Aesthetics, two-page newsletter formats like those of Stagedoor and Kala Sangam magazine’s monthly Kala Aur Kalakaar, theatre journalism in the second half of the twentieth century in India was leaving no stone unturned to uplift theatre practice and create an effective engagement with the society it cohabited. Such an engagement can be gauged from the publication of drama scripts in magazines like Abhinay Sanvad, Rangmanch, Bharatshastra, Chhayanat, Natrang, etc. A three act drama titled ‘Shahidon Ki Basti’ written by Prem Kashyap Souj was published in the 1976-77 yearly issue of Kala Mandir, Gwalior’s Rangmanch. The disclaimers published under these scripts about the terms of permission to use the script and some notes on the stage design justifies the analysis that theatre ephemera possibly opened up pathways for the creation of new theatre circuits in regional spaces and encouraged translations and adaptations.

Theatre ephemera played a significant role in generating awareness on the socio-political nature of theatre as can be evidenced from a letter to the editor written by a reader of Rangbharati magazine in May 1980 on the state of affairs on the cultural front in India with regards to the government policies. Similarly, socio-political issues like the rise of Dalit theatre in the 1970s-80s was discussed by Durga Dixit in the 40th issue of Natarang in 1982 where she demarcates Dalit Theatre from sympathetic representations of the Dalits on the middle-class stage by demonstrating that Dalit theatre-makers staged the experiential realities of caste hierarchies. These views were echoed in Satish Alekar’s interview by Anand Gupt in the weekly newspaper Dinmaan (9-15 March, 1986) where he asserts his support for Dalit Theatre, but agrees that an honest narrative for Dalit theatre can evolve only through lived experiences.

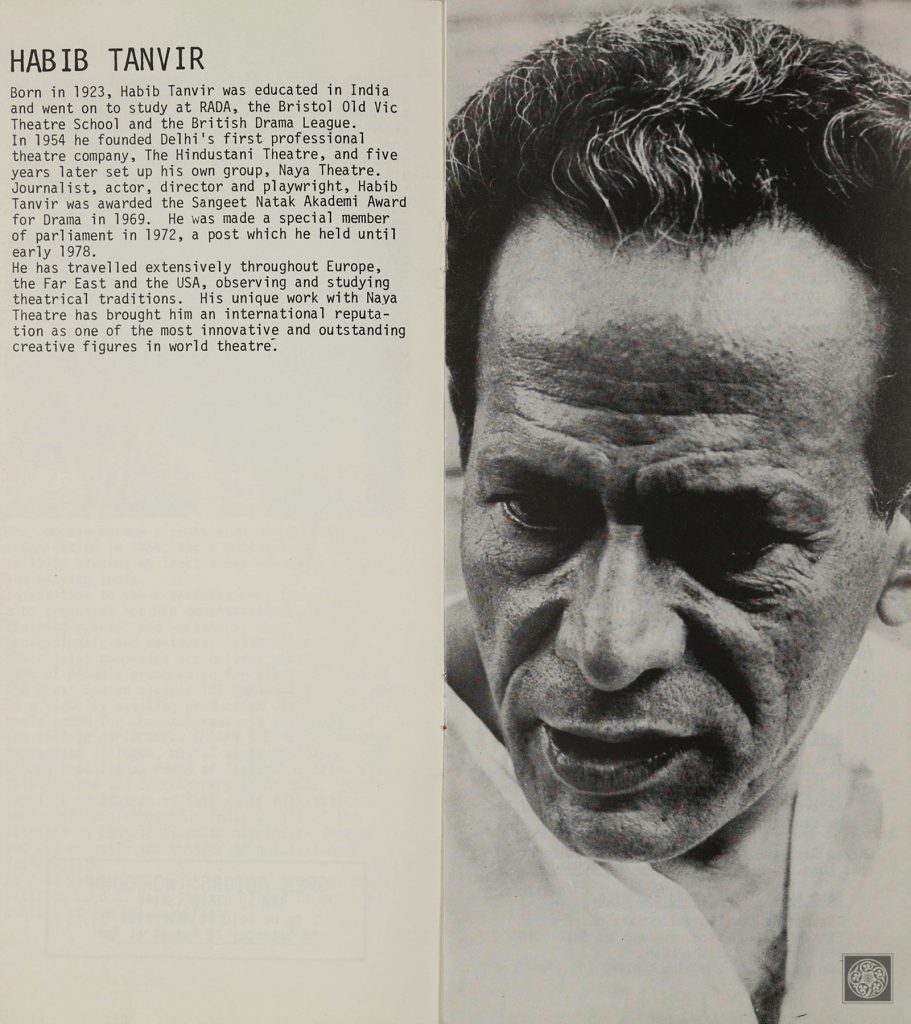

However, as compared to magazines and journals, newspapers, with low cost and thus higher circulation, were instrumental in delivering theatre news in the larger public sphere. Newspapers covered production reviews, announcements of new productions, interviews with actors, impact of censorship, sustainability, portrayal of women in theatre, cultural policies and their implementations, debates on ideological standpoints, discussions on the anxieties emerging from encounters with new age mass communication mediums like radio and televisions, theatre history and the role of theatre in the larger public sphere. For instance, journalist Chitra Subramaniam interview of Naseerudin Shah, Shaukat Kaifi, Dina Pathak, and Farooque Shaikh on the state of contemporary theatre in India published in India Today (dated 15 March 1980) brought the issue of theatre’s sustainability and economics in the public sphere. Theatre news was also distributed and circulated through production brochures and leaflets. E. Alkazi Collection and Anand Gupt Collection consists of hundreds of brochures from the mid twentieth century to the early 2000s. Noting the cast, production companies, funding agencies, time and place of the performance, brochures also give an insight into the making of the play and the techniques employed by directors through blurbs from director’s notes, play synopsis, and photographs. Tanvir’s production brochure of Charandas Chor at the Riverside Studios, London in 1982 when corroborated with newspaper reports shows how theatremakers from India were shifting the focus from the centre (‘national’ theatre) to the peripheries (adapting folk and popular genres and forms) and attempting to create a modern India identity through theatre presentations touring via the theatre circuits. Such brochures also serve as primary sources to map the journey of a play through time and identify the theatre circuits of a particular time period.

Further Readings:

- A Poetics of Modernity: Indian Theatre Theory, 1850 to the Present. Edited by Aparna Bhargava Dharwadker. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2018

- Public Women in British India: Icons and the Urban Stage. Rimli Bhattacharya. Routledge India, 2020

- Role of Theater Magazines: Regional Development or Connecting Internationalism. Nripendra Saha. Winter Issue, Vol.4, No.2, Global Media Journal-Indian Edition, December 2013