by Mridu Rai

Chingrimi Shimray. Millo Ankha. Menty Jamir. Three artists whom I have never met in person, knowing them and their worlds only through their images.And yet, I feel a strong kinship. A connection made and sustained through images, and through one fragile identity. The identity of being a ‘Northeastern’.[1] It is the weight of this identity on image-making practices, a weight so heavy and at the same time so comforting, that I seek to explore more deeply in this essaythrough sharing what I learnt via my conversations with the three artists. My hope is to both embrace and complicate it.

I. The “Northeastern” Myth

The “Northeastern” identity that connects me with these three artists is but an imaginative one. For many people so labelled, its most concrete form manifests only as a feeling. Scholars have consistently argued that there is no single criterion of either ethnicity or geography unifying the eight states – Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Tripura or Sikkim – that constitute Northeast India; they also argue that ‘Northeastern’ is a highly politicised inscription of marginality that in fact exists only in relation to mainstream India.[2] All three artists featured here echo this opinion. ‘Up to Guwahati, I am identified as a Naga. It is only when I am out of the region that I become a “Northeastern” artist,’ says Chingrimi. What are the repercussions on one’s practice and work when one has to associate oneself with an imposed, arbitrary socio-political category that in itself has no concrete meaning? The dominant assumption is that a “Northeastern” is a person from one of these eight states; equally, this identity ‘can mean anything and nothing at the same time’.[3] Not only is the modern generic framing of “Northeastern” thoroughly confused and obscure, it is also ‘a deeply racialised category’ stemming from taxonomies of the colonial knowledge project that registered the Northeast as India’s ‘Mongoloid fringe’.[4] “Northeastern” is, therefore, not only a ‘myth but also mythical’[5] because any use of this descriptor conjures racial – and racist – iconographies, or what Stuart Hall calls stereotypes, where people (and in this case, places) are reduced to a handful of differential traits that are then further pared, exaggerated and reproduced to eternity.[6]

Yes, as “Northeastern” is a contentious identity, I try and use it with care and caution. And yet, this same identity gives “us” all such a strong sense of belonging. This internal conflict, perhaps, is why I have never received definite answers from image-makers about the ramifications of this identity on their practices. All three artists featured here said that while they embraced being a “Northeastern”, it was not a primary association vis-à-vis their relationship to their art. As Menty observed, this is not due to internalised shame about their origins but because of not wanting to be fixed or tied down by anything: ‘When I talk about an artist, where she/he/they are from is not the first thing I speak of but rather their work itself. Why can’t I have that too?’ A valid question. However, throughout the writing of this essay I couldn’t help but wonder: would I, as a writer, and Chingrimi, Ankha and Menty, as artists, have found a space to articulate/be articulated within these few thousand words if it were not for our “Northeastern” being?

II. Situated Practices

Chingrimi Shimray: Rupturing the Archetype

Chingrimi is a visual artist and researcher based in Ukhrul, Manipur. She is currently researching and documenting traditional textiles of the Tangkhul (a Naga tribe), and uses image-making as a form of cultural inquiry. Her series ‘Ivayo!’ [‘Oh! My!’] She Said (2020) documents examples of the clothing her aunt chose to wear during the Covid-19 lockdown. Chingrimi had rarely encountered formal visual or textual representations of the ordinary Tangkhul woman in non-traditional garments. So, she explains, she thought it would be ‘fun’ to visualise her subject as ‘a less romanticised’ indigenous figure. A Tangkhul woman who enjoys wearing ‘thrift-store New Balance trainers’, ‘a flashy pink raincoat’ that matches her nail polish, and fashionable tops that remind one of Japanese contemporary artist Yayoi Kusama’s vibrant productions – can suchitemscause fault lines in the regimes of representation that have essentialised tribal women across the Northeast for the past two centuries? Through her practice Chingrimi continues to reflect on and unravel these questions in relation to the Tangkhul community.

This series attempts to portray a less romanticised vision of the figure/‘type’ of the ‘indigenous woman’. The photographer documents the clothing her aunt chose to wear during the 2020 Covid-19 lockdown, influenced by personal taste and by the nature of domestic activities.

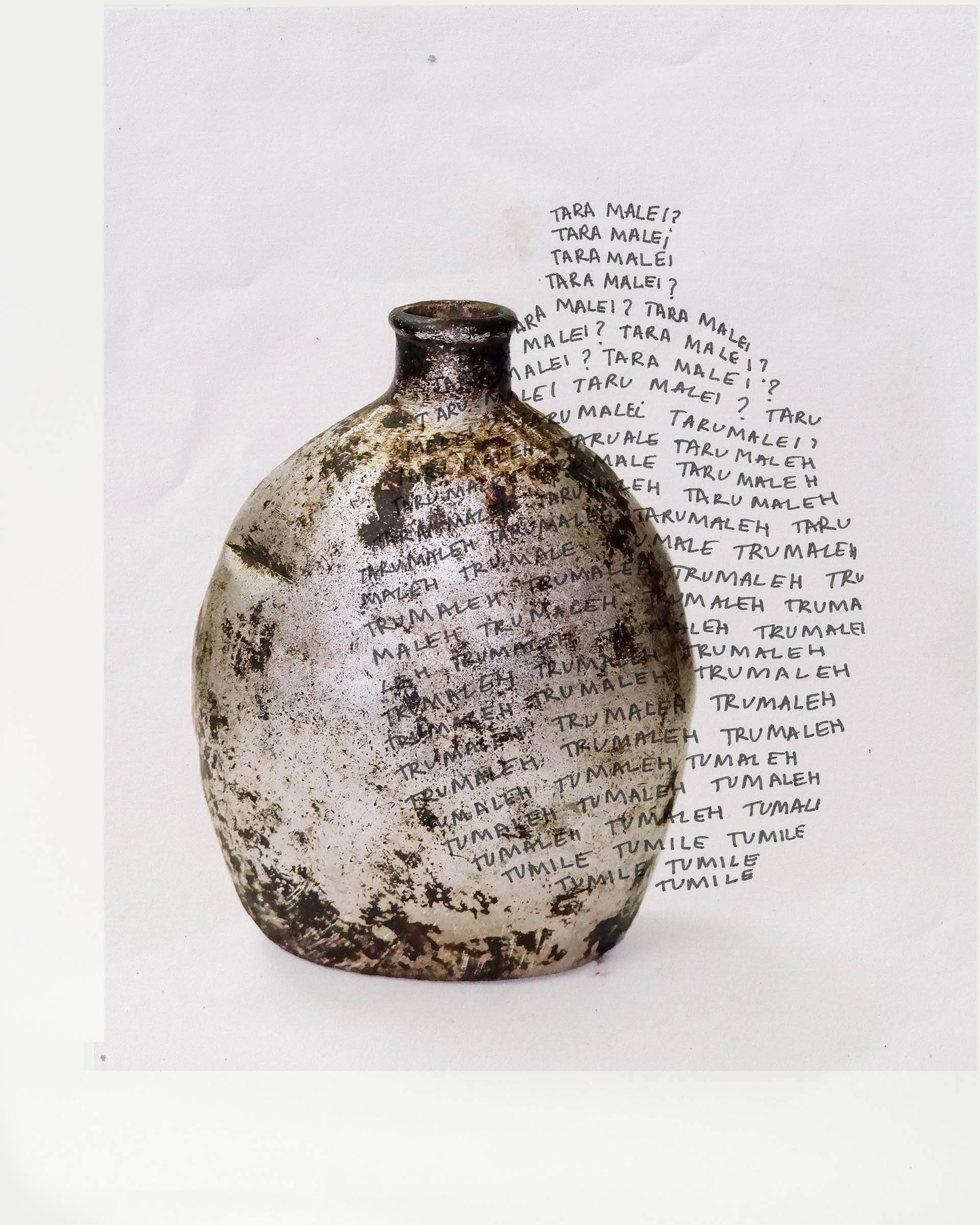

The series explores storytelling through objects within the Tangkhul community. This work presents an aluminium bottle gifted to Chingrimi’s grandmother by a Japanese soldier during the Second World War. The meaning of tumile is uncertain; the artist assumes it derives from ‘taru malei?’ which in Tangkhul translates as ‘Do you have water?’ – perhaps an attempt by Japanese soldiers to communicate in the local language.

Millo Ankha: Expanding the Frame

Like Chingrimi, Ankha, a visual artist and poet from Ziro, Arunachal Pradesh uses image-making as a process of understanding her community, the Apatani. Her project Echo of the Universe (2022)documents women Popi (priests) who have been encouraging the tribe’s women and children to learn about their Apatani faith and indigenous knowledge systems, primarily through songs and dances. This activity is carried out in a community space called Meder Nello. The space, itself a recent development, has allowed women to become active in the production and dissemination of culture, and to experience forms of agency they were previously denied within the tribe’s patriarchal structures. This cultural assertion is important because it provokes another fracture in the dominant mode of visual representation which has endlessly capitalised on the fetishisation of tribal women, including wide use of fetishist images by the neoliberal tourism industry. ‘As a child, I used to see images of Apatani women mostly with tattoos and nose plugs. It made me curious to know if the generations who didn’t have any tattoos were not photographable – like my mother, for instance,’ says Ankha. Additionally, by rendering visible the women at the core of Apatani culture, her images attempt to subvert the rigorous gender paradigms of her tribe. For me, Ankha’s works, including Echo of the Universe, reorient gazes from both within and outside the community, enabling new insight into the cosmos of a particular indigeneity.

This work depicts women Popi (priests) of the Apatani tribe in Ziro Valley, Arunachal Pradesh, and their emergent efforts at building and sharing indigenous knowledge systems through cultural forms.

Eli baniin is a ceremonial procession of the family and relatives of the bride carrying newly reaped rice to the groom’s nesu (granary). The bride carries rice, two ginger plants, cucumber seeds, pumpkin seeds, two eggs, a gourd filled with beer and a hen with her chick to invoke fertility and prosperity. Each grain of rice carried in the procession is stored in the groom’s nesu, followed by propitiation of spirits.

Menty Jamir: Othering the Self

Menty is a freelance photographer from Nagaland, based in Delhi. Our paths crossed for the first time through an image: a self-portrait (Fig. 5) in which, as in most of her work, she uses light and shadow to construct visual poetry, creating an affective equilibrium through evoking antithetical emotions. For me, this is also an image of/made by an indigenous woman that creates yet another schism in the hegemonic visual aesthetics that perpetuate racialised tropes of the exotic and erotic[7], produced initially by colonial ethnographers and reproduced and reified in various postcolonial representations[8], as well as in certain trajectories of postcolonial scholarship. Menty has turned the lens inwards, towards herself, her body. Positioning herself very close to the camera, without offering the viewer any absolute coordinates by which to orient perception, she is in control of both the performance and the gaze, rather than serving as a prop for someone else’s fictive projections. Other viewers might look at it differently, and I don’t know if I am accurate about Menty’s intentions, but this is my reading of the image. The agency to photograph and be photographed resides completely with/within her. Issues around gender have always shaped her being, as is the case with so many women artists negotiating the rigid thresholds of Indian patriarchal custom. Her upcoming project with 8:30 Collective[9], a group of nine women photographers from different parts of India, closely grapples with this theme. To me, this image is a questioning of the prescriptive traditional moralities that both discipline and desire the female form.

In this series of self-portraits, Menty juxtaposes herself with natural elements, whether with dried plants daubed in pearl-like droplets, in a close-up sitting next to a water body, or posed to let her bare back become a canvas absorbing the shadows of sun-drenched flowers. I find these juxtapositions fascinating because they defy any single reading or ‘meaning’. The only certainty is that she is in full control of the image, both as the photographer and as the subject. Menty herself sums it up best when she says that these images celebrate her belonging to herself unabashedly, and that she was never meant to be understood.

As in most of Menty’s images, here light is an active protagonist. Her deft use of line – vertical, horizontal, wavering – allows the eye to wander and discover other sub-plots. I like to experience Menty’s images as if they were multiple stories contained in a single frame. This one is a tale of fleeting moments/lasting emotions.

III. The ‘Unlearning’

The images I’ve shared are all powerful visual narratives in their own unique ways – a small lens to understand the world of these artists. And I wonder if the reader has noticed the absence of the term “Northeastern” whilst I mulled over their practices. Was this a conscious authorial act? Yes … and no. The fact is, these narratives are not about Northeast India and “Northeasterns”. They are about the artists and their lived experiences. They speak to issues and ideas that each practitioner wants to, as Menty says, ‘accept, address and unlearn’. Here, unlearning is key– as a conscious act it embodies what Azoulay calls a process of politically engaging with and questioning concepts and institutions which are based on and fuel imperial conditions.[10] Chingrimi, Ankha and Menty are not just “Northeastern” artists voicing “Northeastern” issues through their image-making. And yet, we’ve bonded here and elsewhere as “Northeasterns”. Even through the homogenisation, we’ve shared creative and critical ideas, cheered each other on, and continue to do so. Is it because we have been denied space otherwise that we’ve been compelled to embrace an enforced identity? An identity forged only through ‘a sense of alienation from the mainland’?[11] Is mainstream photographic discourse only interested in us if we put forward our “Northeastern” identity?[12] I empathise with Ankha when she admits that she has to identify herself as a “Northeastern” artist while submitting proposals for grants. For her, this is important as it contextualises her practice and underscoreswhy she is in a position to tell a particular story. I agree; I too have had to do the same many times, for the same reasons. But I also worry that this tactical self-presentation – undertaken in the wider interest of genuine self-representation – both confirms and contributes to our lack of autonomy.

This brings me to a key concern that many of us from the region have been reflecting upon for quite some time: has the “Northeastern” identity in photographic discourse become a performative one? Not through any deliberate intention of the artists, but moulded over time by the accumulated pressure of unexamined cultural mandates that assure the visibility of our work only if it obediently presents stereotypical “Northeastern” images that can be reflexively slotted within the category of “Northeastern”? Are the parameters of which artistic products get seen or funded driven only by certain images conjured by the terms “Northeast” and “Northeastern”? I fear the price of being subsumed under one single category, especially when it comes with such a heavy history of state and military violence, as well as the violence of the camera. I recall Toukan’s skilful analysis of the subtle but ever-present hegemonic processes that guide the politics and aesthetics of artistic productions in Lebanon, Palestine and Jordan, such that even works of dissent enable the very institutions and structures they critique.[13] If we are obliged to perform our “Northeastern” identity in our image-making practices, will this strategy at some point become counterproductive in terms of a wider politics of resistance in which we are engaged? Yes, stories from different states of Northeast India are coming to the fore, stereotypical iconographies are being reckoned with. Women practitioners, in particular, are generating critical work that shatters the rose-tinted lenses through which indigenous communities are viewed, but it is unfair to simplify and/or celebrate these as only “Northeastern” photographic practices. Regionalism, if present at all in our cultural work, is only one aspect of it.

My conviction thatChingrimi, Ankha and Menty are creating fractures in the dominant regimes of representation through their most personal works is both unsettling and consoling. It acknowledges my fear of a perpetuated essentialism, but also announces my faith in an expanding image spectrum. Kikon declares that indigenous voices have to ‘write and engage with places and questions as though our lives and every bit of sanity depends on it’.[14] The most personal projects for all three artists featured here seem to have emerged from their own beings. Gender is a key aspect of their experiences; their image-making is not an external process but an embodied one; and each practitioner’s creative output is thoroughly infused with her specific individuality. Menty’s long-term personal projectsconsist of reflections, questionings, and honest outpourings vis-à-vis where she is from; and about the themes addressed in her practice, Ankha says, ‘I would be in agony if I didn’t respond to this world.’ When powerfully subjective works are reduced to placement and interpretation under one convenient, flattened, composite discursive field, I see a process of systematic depoliticisation and an overwhelming denial of the region’s deep social complexities. As I mentioned earlier, for centuries the marginalised communities these artists belong to have either been erased from visual representation or inscribed as the alluring exotic/erotic ‘Other’ within mainstream colonial and postcolonial cultural imaginaries. I believe that the new image-making practices are an opportunity to repudiate fatigued existent tropes and typologies and to shape a dynamic “Northeastern” counter-narrative.[15] We have to heed photography’s potential to cause, in Barthesian terms, a disturbance to civilisation.[16]

As I have consistently asserted, the “Northeastern” identity is also one where we “Northeasterns” have found comfort and belonging; my aim is not to disregard it but to open conversations on how the uncritical acceptance of its ‘stubborn persistence’[17] can further reinforce the ongoing marginalisation of artists from the region. Ankha, I feel, effectively summarises our dilemma: ‘I take joy in my belonging and non-belonging through my artistic practice. That keeps me grounded.’

Notes

1. I borrow the term ‘Northeastern’ from Rohini Rai, who describes it as a ‘new racial category’ reconstructed by the postcolonial-neoliberal Indian state to signify the diverse populations of the region, drawing on parameters of colonial ethnography. See Rohini Rai, ‘From Colonial “Mongoloid” to Neoliberal “Northeastern”: Theorizing “Race”, Racialization and Racism in Contemporary India’, Asian Ethnicity, Vol. 23, No. 3 (2022), pp. 442-62 (published online in January 2021).

2. Jelle J.P. Wouters and Tanka B. Subba, ‘The “Indian Face”, India’s Northeast, and “the Idea of India”’, Asian Anthropology, Vol. 12, No. 2 (2013), pp. 126-40. Also see Rohini Rai, ‘From Colonial “Mongoloid” to Neoliberal “Northeastern”’, op. cit.

3. Jelle J.P. Wouters and Tanka B. Subba, op. cit.

4. For recent studies that explore the racialisation of India’s Northeast and Himalayan regions through concepts of the “Mongoloid race” / “Mongolian fringe”, see Rohini Rai, ‘“Northeastern” Delhi: “Race”, Space and Identity in a Postcolonial, Globalising City’, PhD Thesis, University of Manchester (2019); Rohini Rai, ‘From Colonial “Mongoloid” to Neoliberal “Northeastern”’, op. cit.; and Mabel D. Gergan and Sara H. Smith, ‘Theorizing Racialization through India’s “Mongolian Fringe”’, Ethnic and Racial Studies, Vol. 45, No. 2 (2021), pp. 361-82.

5. Jelle J.P. Wouters and Tanka B. Subba, op. cit.

6. Stuart Hall, Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices (London: Sage, 1997).

7. For an account of early ethnologists’ (mis)understanding of the Naga image in colonial photography, see Debojyoti Das, ‘The Construction and Institutionalisation of Ethnicity: Anthropology, Photography and the Nagas’, The South Asianist: Journal of South Asian Studies, Vol. 3, No. 1 (2014), pp. 28-49. Also see photographer Zubeni Lotha’s research and exhibition Looking at the Tree Again (2017) that examines the colonial construction of identity and essentialist representation of the Nagas, in particular the Konyak Nagas, by the Austrian ethnologist Christoph von Fürer-Haimendorf in 1936, who depicted them as a “primitive” people.

8. See Preym K. Po’dar and Tanka B. Subba, ‘Demystifying Some Ethnographic Texts on the Himalayas’, Social Scientist, Vol. 19, No. 219-20 (1991), p. 78. The authors suggest that ‘as legatees of the colonial academic tradition’, Indian social scientists tend to practice a ‘home-grown Orientalism’; the authors also argue that dominant Hindu society is complicit in the process of ‘othering’ tribal communities in India, and in reproducing colonial stereotypes about them through an unquestioning use of received discourse from the West.

9. https://asapconnect.in/post/276/singlealbums/sometimes-magic-looks-like-this

10. Ariella Azoulay, Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism (London/New York: Verso, 2019). Also see Mridu Rai, ‘Revisiting Feminist Archives through Ariella Azoulayʼs “Citizenry of Photography”’, Critical Collective (2021); https://criticalcollective.in/Lens_based_practic.aspx.

11. Jelle J.P. Wouters and Tanka B. Subba, op. cit.

12. For Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s concept of strategic essentialism which foregrounds the notion of how internally diverse groups intentionally come together through shared experiences to perform an essentialised image of themselves in order to attain certain political objectives, see Gerald M. MacLean and Donna Landry, The Spivak Reader: Selected Works of Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak (New York/London: Routledge, 1996).

13. Hanan Toukan, The Politics of Art: Dissent and Cultural Diplomacy in Lebanon, Palestine and Jordan (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2021).

14. Dolly Kikon and Mabel Denzin Gergan, ‘Letters between a Lepcha Geographer and a Naga Anthropologist’, RAIOT, 3 June 2021; https://raiot.in/letters-between-a-lepcha-geographer-and-a-naga-anthropologist/

15. Nicholas Mirzoeff, The Right to Look: A Counterhistory of Visuality (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011).

16. Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, trans. Richard Howard (London: Vintage Books, 2000).

17. Mabel D. Gergan and Sara H. Smith, ‘Theorizing Racialization through India’s “Mongolian Fringe”’, op. cit.

Mridu Rai is the co-founder of the Confluence Collective. She is currently pursuing her PhD in visual anthropology from University College London. She is the recipient of the Critical Collective-PhotoSouthAsia Young Writers Award (2021) for lens-based practices and the IFA Art Research Grant 2021. Her exhibition How Do I Bring You Home? (2022) was shown at the Royal Anthropological Institute, London.