by Agastaya Thapa

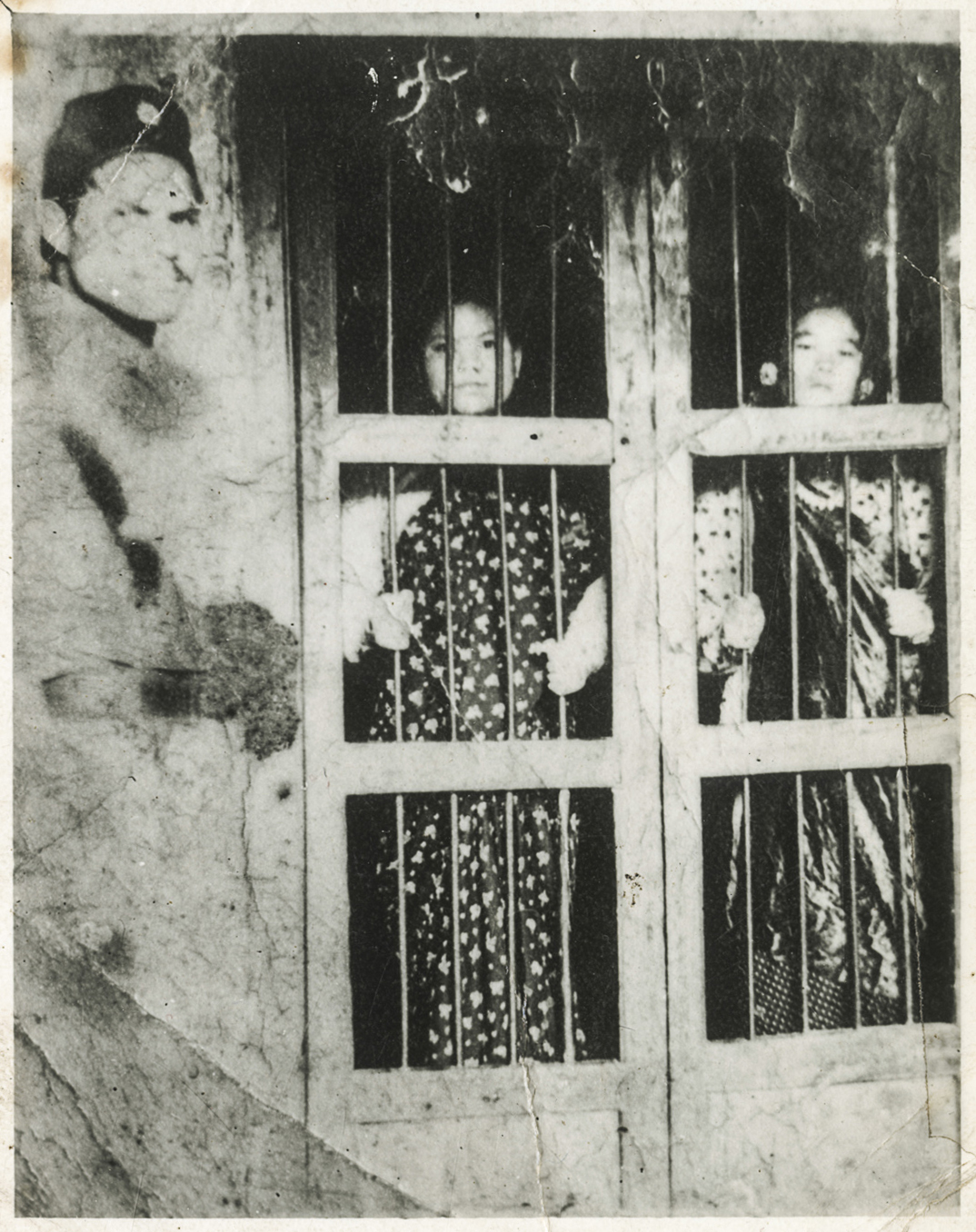

The explosive and often subversive power of photography has served many political and social movements, and of late, the quiet historical force of the photograph has been well understood and channelised by scholars, practitioners and cultural initiatives committed to the recuperation and re-inscription of women’s history all over the world. Photography has had an important role to play in the history of the women’s movement in Nepal, in bearing witness to innumerable stories eclipsed, forgotten or tucked away in the remote, dust-swathed, occluded reaches of the past. Recently the power of the photograph to activate or trigger memories of important objects, people and events came in the form of a small, blemished, crinkled, black-and-white image. Sontag declares that photographs ‘furnish instant history, instant sociology, instant participation’[1] – and this rare, old, weathered photograph, taken at the Dillibazar Prison in Kathmandu in 1961, draws us at once into its aura, suggesting a powerful story of resistance and resilience. It captures the defiant faces of two young women grasping their prison bars as they squarely face the camera; a guard stationed to keep watch over them is also present, staring into the lens. These incarcerated women would be identified as Prem Kumari Tamang of Nuwakot and Lal Maya Tamang of Dhading, arrested for their opposition to the 1960 coup d’etat by King Mahendra (1920-1972).[2]

This historic photograph is from the collection of Shanta Shreshta, feminist and political activist. A revolutionary who fervently agitated for democracy and women’s rights, Shrestha was only twelve years old when, as the youngest delegate of the Nepal Women’s Association, she marched to demand suffrage for women during the dictatorial and isolationist Rana regime.[3] It wasn’t surprising, then, that a photograph depicting women who had dared to violate traditional boundaries at a particular historical moment should be in the possession of someone so committed to the arduous fight for gender equality in the new political dispensation.

In 2018, the first phase of the Feminist Memory Project (FMP) opened to the public at the historical site of Patan Durbar Square, Lalitpur in the form of The Public Life of Women: A Feminist Memory Project, an exhibition and ‘archival campaign’[4] undertaken by the Nepal Picture Library (NPL).[5] It was part of Photo Kathmandu, a biennial international festival dedicated to showcasing diverse contemporary photographic practices and serving as a platform for pluralistic and collaborative artistic, research and pedagogic initiatives that link to local concerns and conversations. Various sites around Patan, still under repair after the catastrophic 2015 earthquake, were selected to host the intricate history of the women’s movement in Nepal. Underscoring the ‘public’ element in the conceptualisation of the multipart exhibition, Photo Kathmandu ensured that for the duration of a month, people in and around Lalitpur would each day be exposed to photographs and documents focusing on feminist history. This exploration of “publicness” or relationship with public life in the context of the feminist experience in Nepal was a theme which emerged out of and was highlighted by the materials collected during FMP. The active configuration of the project as a revisionist campaign affirmed that this particular undertaking was not simply a standard reiteration of historical materials but was oriented towards something more charged and disruptive.

Photograph: Chemi Dorje. Courtesy: Nepal Picture Library.

The contest between the private and public is critical to any study of gender, and the negotiation between the private and the public is always a complex matter. In Nepal, as in all traditional societies, women emerging from the private sphere into the public fold, to be visible, vocal and accounted for, is without doubt a radical preliminary gesture that would ideally manifest in other public forms of gender emancipation. Tracing feminist history through visual means has been an extensive and challenging exercise; collecting photographs necessitated direct and sustained communication and engagement with women and their layered personal/social lives through oral history sessions. It became apparent that for project participants the first step – transgressing the boundaries of the private realm to become visible in the public sphere – was a common, unifying, initial experience of empowerment and of an expanded sense of self.

The Public Life of Women: A Feminist Memory Project was divided into six thematic sections, all dealing with the different means adopted by women to stake their claim to public life: politics, education, civil society, writing, travelling, and the personal. Photographs and allied documentary materials as well as objects such as letters, pamphlets, reports, magazines, chapbooks, tables, chairs, bed, cabinet, knick-knacks, books and diaries were displayed. Viewers thus saw images of women – some identifiable and some anonymous – addressing pro-democracy rallies, marching, protesting, picketing, posing, relaxing, reading, writing, riding, and so on. One section was ‘A Room of One’s Own’, on the theme of personal space.[6] Here the complex relationship between private and public was brought into focus through the questioning of the intent behind the re-creation of the private room of Nepali author Parijat (1937-1993) as an intimate space of retreat, assembled as an exhibit with the author’s personal effects obtained from Parijat Smriti Kendra (Parijat Memorial Centre).[7] This issue was resolved by stressing that women’s private/personal space can be just as emancipatory as their public presence. Parijat’s room was a manifestation not only of feminist self-belief/self-assertion, but also of memorialising practices undertaken by women to preserve their pasts, based on the belief in a historical continuity with a feminist future.

Photograph: Chemi Dorje. Courtesy: Nepal Picture Library.

Parijat’s room is also an example of how the memorialisation of feminist agency becomes integral to the process of formation of feminist subjectivities.This understanding is reflected in how the FMP was conceived and strategized – to make public not merely previously obscured moments of women’s history, but also to keep transparent/public the manner in which the exhibition was planned to display and present archival materials to the viewing public. A double register of movement can be tracked: one showcasing the journey of Nepali women from the inner/private to the outer/public, and the other transforming what were hitherto personal memories stored in the form of photographs, letters and diaries into public memory through public modes of display and circulation. The institutionalisation of these materials in the form of an archive further accentuates the process of connecting it with some kind of public memory.[8] More specifically, the photographic form is considered to be amenable with the ‘model of the archive’ as this model is said to influence the ‘character of truths and pleasures experienced in looking at photographs’ so much so that one can posit that ‘archival ambitions and procedures are intrinsic to photographic practice’.[9] Thus, for a digital photographic archive such as NPL, working with feminist memory and women’s history was befitting, as this aligns with recent trends in the study of photography underscoring the agency of photographs in human relations in terms of ‘extending or replacing embodied experiences and connecting with spiritual ones, such as… historical experience, imagination and memory’.[10] These trends enter image discourses through material culture, often adopting anthropological approaches.[11]

At Photo Kathmandu 2018, one FMP event was a special session dedicated to the practice of photo-elicitation, a methodology utilised by NPL whereby photographs were used to draw out responses to interview questions and to narratives by and about women. About seven women contributors to the project were invited to be part of the programme. Using photographs from the FMP archive, the subjects were free to reminisce, rediscover and retrieve parts of feminist history through their stories. Re-enactments of the past through archival practices such as photo-elicitation points to the importance of what Annette Kuhn calls ‘performances of memory’ which help to embody, express and unpick connections between the private/personal and the public/social.[12]

Hence photographs, used to ‘catalogue’[13] some well-known as well as hidden facets of the women’s movement in Nepal became the project’s raison d’etre. A good number of private and institutional sources provided support for this exhibition, in which selected images and documents were in no way to be treated as visual substitutes for a formal historical narrative of women’s history in Nepal. Rather, the arrangement and organisation of the various photographs and related ephemera would allow exhibition viewers’ access to historical information not as a typical linear chronology but as bricolage – disjointed, discrete fragments that viewers themselves would have to mentally juxtapose/combine in order to experience them as meaningful assemblages. Viewers were inundated with an abundance of photographs, documents, objects and texts that were worked into the display. Thus, the sheer force of volume – central to the initial curatorial intent – was a primary variable within display strategy. As visitors milled around in the specified public display spaces, a common complaint of visual and textual excess began surfacing. This was readily welcomed by Diwas Raja KC, one of the Chief Curators, as a sign of having achieved one of the exhibition’s main goals – to confound and confuse complacent viewers who tend to reflexively trivialise and categorise any cultural activity associated with women as advocating for “women’s rights and women’s empowerment”; the display tactic of deliberate overload was a way of challenging customary viewing practices and simplistic conditioned responses, and of letting viewers know ‘that they really don’t get it! Feminism and women’s history are actually very intricate subjects’.[14]

Photograph: Ashwin. Courtesy: Nepal Picture Library.

Subsequently, the FMP exhibition has travelled to many more venues and locations across the globe. An abridged version of the project was exhibited by co-Chief Curator NayanTara Gurung Kakshapati at two venues in New Delhi: Khoj (2018) and India Art Fair (2019). In 2021 the project was featured as part of the exhibition Growing like a Tree curated by photographer Sohrab Hura at the Ishara Art Foundation, Dubai. Titled Underground Biographies, the FMP contribution showcased the lives of Sushila Shreshta and Shanta Manavi, two women members of the underground Communist Party in Nepal. Enduring hardship and peril for their political and ideological beliefs, both women were engaged in underground work for their party between the 1960s and 1990, the year Nepal became a constitutional monarchy after decades of the partyless Panchayat regime set in place by King Mahendra. Sometimes working incognito under assumed identities, these women travelled across Nepal and to India for party work, raised families under the shadow of a political ban, lived as fugitives and resisted capture and confinement. The task of making public their stories and wilfully secret lives in the underground communist movement was achieved by curating their photographs, letters and other documents into a timeline.

The logic behind choosing the archival medium was that it seemed to most effectively convey and reflect the overarching idea of the project: a feminist telling of the lives of “difficult women” – those who in one way or another emerge from patriarchy-endorsed social passivity, anonymity and absence, and assert their claims to selfhood, autonomy and agency, the right to self-representation, and to full citizenship. This narrative was shaped through ephemera: transient, “minor”, paper-based items such as photographs, letters and postcards considered ‘not really substantial as archival material’.[15] These do not fit well into the organisational structure of collecting institutions and are often regarded as “difficult materials” by librarians and archivists. As postcards reproduced from originals in the FMP archive were readily distributed among viewers in several iterations of the exhibition, one can easily imagine that in the future, these apparently insignificant but actually untameable scraps could serve as a vital, substantial line of defence against the corrosion of feminist history in Nepal.

Notes

1. Susan Sontag, On Photography (New York: Delta Books, 1973).

2. Until the 1950s Nepal had retained its monarchical form of governance. In 1959 the crown decided to give multi-party democracy an opportunity. Elections were held in 1960 and the centre-left Nepali Congress Party won under the leadership of B.P. Koirala (1914-1982), who was elected Prime Minister. However, on 15 December 1960 King Mahendra staged a coup d’etat, dismissed the parliament, abolished the Constitution and party politics, imprisoned Koirala, and introduced the partyless Panchayat system of direct rule.

3. From 1846 to 1951 Nepal was ruled by the Ranas, a vast and multi-branched family who seized power from the ruling Shah dynasty in 1846 following a bloody coup spearheaded by Jung Bahadur Rana. A succession of hereditary prime ministers who titled themselves “maharajas” took over governance, initiating a regressive and oppressive political and economic programme which isolated Nepal from the world. This hindered development on all fronts, including education, industrialisation and infrastructure.

4. The Public Life of Women: A Feminist Memory Project (2018-ongoing), Feminist Libraries and Archive Network, accessed 12 June 2022. The archival campaign was part of a research grant received by the Nepal Picture Library from Magnum Foundation, New York; https://fla-network.com/exhibitions/exhibition-the-public-life-of-women-a-feminist-memory-project/. Online text accompanying a photo essay on the project (The Caravan, 1 June 2019) explains that the archive, ‘which now stands at close to eight thousand photographs, makes evident that despite women having played critical roles in political, social and cultural spheres of history, they have failed to be recognised or remembered for their contribution. While the narratives of women have often been cast, if at all, in light of their struggles in domestic spaces, their participation in public life has largely been ignored or considered anecdotal, at best. The archive, particularly being one that is visual, seeks to offset this notion, paving the way for a history of a country to be seen through an alternate lens.’ https://caravanmagazine.in/photo-essay/archive-traces-feminist-history-nepal

5. Co-founded by NayanTara Gurung Kakshapati, the Nepal Picture Library (NPL) is a digital photographic archive that has built a vibrant visual repository of Nepal’s history, providing a more inclusive and democratic approach to the nation’s past. Reflecting aspects of ordinary life, social history and public culture, its pluralistic, democratic content is distinct from a conventional visual “history of`Great Men”/related meta-histories generally taken to constitute the dominant “national” narrative. https://www.nepalpicturelibrary.org/

6. Taking inspiration from British author Virginia Woolf, who in her extended essay A Room of One’s Own (1929) made the argument, radical within the claustrophobic patriarchal restrictions/prescriptions of her time, that women had the formal right to higher education, and to private space and personal autonomy so that they could freely think and write – contingent on having the financial resources and social privilege/support to be able to create/maintain such a space for themselves. For complete essay text online, see http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks02/0200791h.html

7. The Parijat Smriti Kendra (Parijat Memorial Centre) in Kathmandu was established by Sukanya Waiba, sister of the renowned Nepalese writer Bishnu Kumari Waiba (1937-1993) who was popularly known as Parijat. As stated on the Feminist Libraries and Archives Network website: ‘Through a recreation of Parijat’s room, we interrogate the feminist possibilities emerging from the literal and figurative space of women. Parijat was one of the most beloved and influential Nepali writers of her times. Her room was where she spent much of her time due to rheumatism. It was also the place where Kathmandu’s intellectuals routinely gathered to discuss freedom and progress. We displayed some of Parijat’s original belongings, preserved by Parijat Smriti Kendra and Sukanya Waiba, along with a few recreations of memorabilia and memories associated with her room.’ https://fla-network.com/exhibitions/exhibition-the-public-life-of-women-a-feminist-memory-project/

8. Thomas Osborne, ‘The Ordinariness of the Archive’, History of the Human Sciences, Vol. 12, No. 2 (1999), p. 52.

9. Allan Sekula, ‘Reading an Archive: Photography between Labour and Capital’ in The Photography Reader, ed. Liz Wells (London and New York: Routledge, 2003), p. 444.

10. Elizabeth Edwards, ‘Photography and the Material Performance of the Past’, History and Theory,Vol. 48, No. 4 (2009), p. 134.

11. Prominent examples of studies foregrounding material, cultural and anthropological approaches to photography include Pierre Bourdieu with Luc Boltanski, Robert Castel, Jean-Claude Chamboredon and Dominique Schnapper (1965), Photography: A Middle-brow Art, trans. Shaun Whiteside (reissued: Stanford University Press, 1990); Anthropology and Photography 1860-1920, eds. Elizabeth Edwards and Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992); and Christopher Pinney, Photos of the Gods: The Printed Image and Political Struggle in India (London: Reaktion Books, 2004).

12. Annette Kuhn, “Memory Texts and Memory Work: Performances of Memory in and with Visual Media’, Memory Studies, Vol. 20, No. 10 (2010), p. 2. Also see Barbara Misztal, Theories of Social Remembering (Maidenhead and Philadelphia: Open University Press, 2003).

13. Mridu Rai, ‘A Curator’s Quotes’, Artem (January-February 2019), p. 92.

14. ibid.

15. Anisha Baid, Archiving Oral Histories in Photographs: In Conversation with Diwas Raja KC (Part I), filmed February 2021. Online video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VGv5x879P-s&feature=emb_title, at 8:42.

Agastaya Thapa is a Delhi-based researcher and writer. She completed her PhD from the School of Arts and Aesthetics at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, in 2017. Her thesis, Circuits of Representation: Visual Art Practices and the Formation of the Subject in Darjeeling from the Colonial Period to the Present, examined regional representation as shaped by the lens of colonial ethnology and tourist art. Her research interests include colonial visual culture, photography, popular paintings and prints, Eastern Himalayan history and socio-political movements.